(Press-News.org) LAWRENCE -- Much like coronavirus, circulating HIV-1 viruses mutate into diverse variants that pose challenges for scientists developing vaccines to protect people from HIV/AIDS.

"AIDS vaccine development has been a decades-long challenge partly because our immune systems have difficulty recognizing all the diverse variants of the rapidly mutating HIV virus, which is the cause of AIDS," said Brandon DeKosky, assistant professor of pharmaceutical chemistry and chemical & petroleum engineering at the University of Kansas.

In the past five years, tremendous progress has been made in identifying better vaccine methods to protect against many different HIV-1 variants. One important step was when scientists at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease's Vaccine Research Center discovered a promising antibody called vFP16.02. Antibodies are proteins the immune system deploys to target and destroy pathogens and viruses -- and scientists at the NIH determined that the vFP16.02 stimulated by a vaccine had potential to effectively fight HIV-1.

To further understand the promise of vFP16.02-like immune responses as the basis for an eventual vaccine against HIV-1, the team at the NIH/NIAID Vaccine Research Center partnered with the Immune Engineering Laboratory at the KU School of Pharmacy, where scientists in DeKosky's lab set about understanding how the same antibody-based approaches could be even more powerful in the fight against diverse HIV antigens.

Their encouraging findings were just published in the peer-reviewed journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), showing several important mechanistic features about immune protection, including the binding strength of the antibody directly correlated to its ability to neutralize HIV-1.

Co-lead author Bharat Madan, a postdoctoral researcher in the DeKosky lab, led the work.

"We wanted to see whether we could further increase the potency and neutralization breadth of this antibody," Madan said. "That means you could give a lower amount of antibody to someone as a prophylaxis, and it's going to produce a much better and broader immune response. There are various clades of HIV viruses --now I think you must be hearing about various versions of SARS-CoV-2 like the U.K. variant and the South African variant -- likewise, HIV also is quite diverse."

Madan and colleagues used high-throughput screening platforms based on modified yeast cells to display antibody variant proteins, and advanced cell sorting and next-generation DNA sequencing explore a vast library of possible alterations (also known as mutations) to the vFP16.02 antibody. They analyzed the antibodies' response against 208 different HIV strains and "determined the genetic, structural and functional features associated with antibody improvement or fitness."

"In this study, Bharat and colleagues made artificial pathways of anti-HIV-1 immune responses to identify what does and does not work for achieving better protection against HIV-1," DeKosky said. "The results were a bit surprising and showed that the pathway to effective HIV-1 protection might be much shorter than we previously thought."

The research focused on improving structural and biophysical features in the antibodies that bind to the HIV fusion peptide, "a known vulnerable site on HIV-1."

"There are certain regions on this antibody which are more prone to accept the mutation that can enhance the binding affinity towards the fusion peptide," Madan said. "We found a variant or a mutation -- kind of a cluster towards the bottom portion of the antibody we call the framework region -- that can enhance binding strength, and that correlates not towards a particular variant, but to more diverse HIV strains as well."

The most effective variants in the library of mutants boosted the ability of vFP16.02 to recognize and bind to both soluble fusion peptides and the full HIV-1 envelope protein that is involved in viral entry of host cells. These antibody variants, which had mutations concentrated in antibody framework regions, achieved up to 37% neutralization breadth compared to 28% neutralization of the unmodified vFP16.02 antibody.

While the work won't immediately result in development of a vaccine, it could point the way forward for vaccines that would protect against an array of HIV-1 variants.

"The study does a deep dive into the mechanisms of how the immune system specifically recognizes HIV-1 in ways that lead to protective benefits," Dekosky said. "It reveals some of the key insights in how to best target HIV-1 proteins in the next generation of vaccine designs."

INFORMATION:

The KU team collaborated with colleagues and partners including Baoshan Zhang, Peter Kwong and Nicole Doria-Rose at the NIAID Vaccine Research Center and Lawrence Shapiro at Columbia University.

The researchers say they're now working on exploring these same immune pathway features in different settings to determine how they can best "nudge" the immune system toward HIV-1 immune protection.

Philadelphia, March 12, 2021 - Researchers from Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) have determined what happens at a cellular level as the lung alveolus forms and allows newborns to breathe air. Understanding this process gives researchers a better sense of how to develop therapies and potentially regenerate this critical tissue in the event of injury. The findings were published online today by the journal Science.

The lung develops during both embryonic and postnatal stages, during which lung tissue forms and a variety of cell types perform specific roles. During the transition from embryo to newborn is when the alveolar region of the lung ...

Skoltech researchers were able to show that patterns that can cause neural networks to make mistakes in recognizing images are, in effect, akin to Turing patterns found all over the natural world. In the future, this result can be used to design defenses for pattern recognition systems currently vulnerable to attacks. The paper, available as an arXiv preprint, was presented at the 35th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-21).

Deep neural networks, smart and adept at image recognition and classification as they already are, can still be vulnerable ...

An enzyme called MARK2 has been identified as a key stress-response switch in cells in a study by researchers at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Overactivation of this type of stress response is a possible cause of injury to brain cells in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. The discovery will make MARK2 a focus of investigation for its possible role in these diseases, and may ultimately be a target for neurodegenerative disease treatments.

In addition to its potential relevance to neurodegenerative diseases, the finding is an advance in understanding basic cell biology.

The paper describing ...

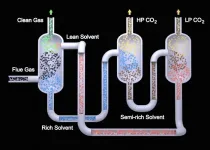

RICHLAND, Wash.--As part of a marathon research effort to lower the cost of carbon capture, chemists have now demonstrated a method to seize carbon dioxide (CO2) that reduces costs by 19 percent compared to current commercial technology. The new technology requires 17 percent less energy to accomplish the same task as its commercial counterparts, surpassing barriers that have kept other forms of carbon capture from widespread industrial use. And it can be easily applied in existing capture systems.

In a study published in the March 2021 edition of International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control, researchers from the U.S. Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory--along with collaborators from ...

MADISON, Wis. -- Mexican wolves in the American Southwest disappeared more quickly during periods of relaxed legal protections, almost certainly succumbing to poaching, according to new research published Wednesday.

Scientists from the University of Wisconsin-Madison found that Mexican wolves were 121% more likely to disappear -- despite high levels of monitoring through radio collars -- when legal rulings permitted easier lethal and non-lethal removal of the protected wolves between 1998 and 2016. The disappearances were not due to legal removal, the researchers say, but instead were likely caused by poachers hiding evidence of their activities.

The findings suggest that consistently strong protections for endangered predators lead ...

Fossil sites sometimes resemble a living room table on which half a dozen different jigsaw puzzles have been dumped: It is often difficult to say which bone belongs to which animal. Together with colleagues from Switzerland, researchers from the University of Bonn have now presented a method that allows a more certain answer to this question. Their results are published in the journal Palaeontologia Electronica.

Fossilized dinosaur bones are relatively rare. But if any are found, it is often in large quantities. "Many sites contain the remains of dozens of animals," explains Prof. Dr. Martin Sander from the Institute ...

For the first time ever, a Northwestern University-led research team has peered inside a human cell to view a multi-subunit machine responsible for regulating gene expression.

Called the Mediator-bound pre-initiation complex (Med-PIC), the structure is a key player in determining which genes are activated and which are suppressed. Mediator helps position the rest of the complex -- RNA polymerase II and the general transcription factors -- at the beginning of genes that the cell wants to transcribe.

The researchers visualized the complex in high resolution using cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), ...

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is already widely used in medicine for diagnostic purposes. Hyperpolarized MRI is a more recent development and its research and application potential has yet to be fully explored. Researchers at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) and the Helmholtz Institute Mainz (HIM) have now unveiled a new technique for observing metabolic processes in the body. Their singlet-contrast MRI method employs easily-produced parahydrogen to track biochemical processes in real time. The results of their work have been published in Angewandte ...

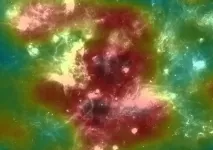

At the heart of Cygnus, one of the most beautiful constellations of the summer sky, beats a source of high-energy cosmic ray particles: the Cygnus Cocoon. An international group of scientists at the HAWC observatory has gathered evidence that this vast astronomical structure is the most powerful of our galaxy's natural particle accelerators known of up to now.

This spectacular discovery is the result of the work of scientists from the international High-Altitude Water Cherenkov (HAWC) gamma-ray observatory. Located on the slopes of the Mexican Sierra Negra volcano, the observatory records high-energy particles and photons flowing from the abyss of space. In the sky of the Northern Hemisphere, their brightest source is the region known as the Cygnus Cocoon. At the HAWC, it was established ...

Geologists have long thought tectonic plates move because they are pulled by the weight of their sinking portions and that an underlying, hot, softer layer called asthenosphere serves as a passive lubricant. But a team of geologists at the University of Houston has found that layer is actually flowing vigorously, moving fast enough to drive plate motions.

In their study published in Nature Communications, researchers from the UH College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics looked at minute changes in satellite-detected gravitational pull within the Caribbean and at mantle tomography images - similar to a CAT Scan - of the asthenosphere under the Caribbean. They found ...