(Press-News.org) (Philadelphia, PA) - About 6.2 million Americans suffer from heart failure, an incurable disease with a staggering mortality rate - some 40 percent of patients die within five years of diagnosis. Heart failure is one form of heart disease, for which new therapies are desperately needed.

Now, in new work, scientists at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine (LKSOM) at Temple University identify a path to a promising novel therapeutic strategy, taking aim at a molecule in the heart known as G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 (GRK5). In a study published online in the journal Cardiovascular Research, the scientists show in mice that reducing GRK5 levels can significantly improve survival following heart attack.

"Previous studies had found that GRK5 is elevated in patients with heart failure," explained Claudio de Lucia, MD, PhD, an associate scientist in the Center for Translational Medicine at LKSOM and lead author on the new study. "Our new research, in mice that experienced myocardial infarction (heart attack), shows that GRK5 overexpression is associated with physiological changes in the heart that decrease cardiac function."

Too much GRK5 in the heart was further linked to increased recruitment of immune cells into damaged heart tissue and harmful inflammation. The combination of these factors - reduced heart function and an influx of immune cells and inflammation - ultimately contributed to increased mortality in mice after heart attack.

Dr. de Lucia and colleagues, working with Walter J. Koch, PhD, W.W. Smith Endowed Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine, Professor and Chair of the Department of Pharmacology, Director of the Center for Translational Medicine at LKSOM, and senior investigator on the new study, examined GRK5 levels in the heart eight weeks after mice experienced heart attack. By that time, animals had developed a condition known as post-ischemic heart failure, in which heart function declines over time owing to reduced blood supply. Tissue damage that impairs circulation in the heart ultimately starves heart cells of the oxygen and nutrients they need to keep the heart working.

After establishing a link between increased GRK5 expression, decreased heart function, and decreased survival in the weeks following heart attack, the researchers explored the effect of manipulating GRK5 to lower its levels in the heart. To do this, they developed a GRK5 knockout mouse model, in which GRK5 expression was eliminated specifically from heart cells.

"After heart attack, our GRK5 knockout mice had much better heart function and better survival curves compared to wild-type mice with normal GRK5," Dr. de Lucia explained. "This raises the possibility that GRK5 inhibition may be a viable therapeutic strategy in human patients, as well."

The team's future work will focus on GRK5 inhibitors and understanding their effects in animals with heart disease.

"Highly selective drugs that block GRK5 are already available," Dr. de Lucia said. "Our next step is to test these agents in animal models of heart failure in order to determine their effect on cardiac function and survival."

Dr. Koch added, "Targeting abnormal levels and activity of GRK5 would represent a totally new drug class [for heart failure] that we hope will add important and innovative value to our fight against heart disease."

INFORMATION:

Other researchers who contributed to the study include Laurel A. Grisanti, Department of Biomedical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Missouri; Giulia Borghetti and Steven R. Houser, Cardiovascular Research Center, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University; Michela Piedepalumbo, Jessica Ibetti, Anna Maria Lucchese, Eric W. Barr, Rajika Roy, Ama Dedo Okyere, Haley Christine Murphy, Erhe Gao, and Douglas G. Tilley, Center for Translational Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University; Giuseppe Rengo, Department of Translational Medical Sciences, Division of Geriatrics, Federico II University, Naples, Italy.

The research was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association.

Scientists have long theorized that supermassive black holes can wander through space--but catching them in the act has proven difficult.

Now, researchers at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian have identified the clearest case to date of a supermassive black hole in motion. Their results are published today in the Astrophysical Journal.

"We don't expect the majority of supermassive black holes to be moving; they're usually content to just sit around," says Dominic Pesce, an astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics who led the study. "They're just so heavy that it's tough to get them going. Consider how much more ...

Since the pandemic hit, researchers have been uncovering ways COVID-19 impacts other parts of the body, besides the lungs.

Now, for the first time, a visual correlation has been found between the severity of the disease in the lungs using CT scans and the severity of effects on patient's brains, using MRI scans. This research is published in the American Journal of Neuroradiology. It will be presented at the 59th annual meeting of the American Society of Neuroradiology (ASNR) and has also been selected as a semifinalist for that organization's Cornelius Dyke Award.

The results show that by looking at lung CT scans of patients diagnosed with COVID-19, physicians may be able to predict just how badly they'll experience other ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - A new Penn State and Cornell study describes an effort to produce the most comprehensive and high-resolution map yet of chromosome architecture and gene regulation in yeast, a major step toward improving understanding of development, evolution and environmental responses in higher organisms.

Specifically, the study mapped precise binding sites of more than 400 different chromosomal proteins in the yeast genome, most of which regulate the expression of genes.

Yeast cells provide a simple model system with 6,000 genes, most of which are found in other organisms, including humans, making them excellent candidates for studying fundamental genetics and complex biological pathways.

The paper, "A High-Resolution Protein Architecture of the Budding Yeast ...

Around three times as many males are diagnosed with autism than females. This suggests that biological sex factors may play a role in the development and presentation of autism.

Studies on the neurobiology (brain biology) of males and females with autism have begun to examine brain networks but results have been mixed. This is largely due to the limited availability of data from autistic females.

In response, researchers from END ...

Humans rely on nature extensively for everything from food production to coastal protection, but those contributions might be more threatened than previously thought, according to new findings from the University of Colorado Boulder.

This research, out today in Nature Communications, looked at three different coastal food webs that include those services provided to humans, or ecosystem services, and found that even if the services themselves aren't directly threatened, they can become threatened when other species around them go extinct--often called secondary ...

More than one million operations are performed in Switzerland every year. A surgeon's skill has a direct impact on the outcome of the operation. Training and experience, as well as momentary fatigue and other influencing factors all play a role. At present, skill is tested by experts, either directly during an operation or by evaluating video footage. This approach is very costly and only a limited number of experts are available. Moreover, the assessment may vary and is not always fully reproducible. For some time, attempts have been made to automate and objectify the assessment of surgeons' skills.

Proof of feasibility

The key result of the study is the proof of the fundamental feasibility of an ...

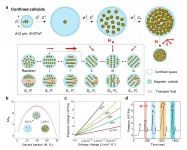

Colloidal suspensions of microscopic particles show complex and interesting collective behaviors. In particular, the collective dynamics of colloids is fundamental and ubiquitous for materials assembly, robotic motion, microfluidic control, and in several biological scenarios. The collective dynamics of confined colloids can be completely different from that of free colloids: for instance, confined colloids can self-organize into vortex structures, coherent motion, or different phase behaviors. On one hand, due to the complexity of colloidal suspensions, how to finely tune the ...

As the world continues to grapple with the COVID-19 pandemic, an international team of researchers have published a review of the best techniques to collect airborne aerosols containing viruses.

In the review, which was published by the Science of the Total Environment journal, a team led by the University of Surrey concluded that the most effective way to collect and detect airborne pathogens, particularly viruses, was to use cyclone sampling techniques.

For example, the sampler draws the air through the cyclone separator. It then uses centrifugal forces to collect the particles on a sterile cone containing the liquid collection vessel, such as DMEM (Dulbecco's minimal essential ...

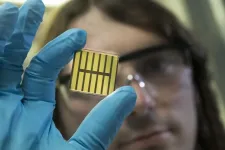

Photovoltaics decisively contributes to sustainable energy supply. The efficiency of solar cells in directly converting light energy into electrical energy depends on the material used. Metal-halide perovskites are considered very promising materials for solar cells of the next generation. With these semiconductors named after their special crystal structure, a considerable increase in efficiency was achieved in the past years. Meanwhile, perovskite solar cells have reached an efficiency of up to 25.5 percent, which is quite close to that of silicon ...

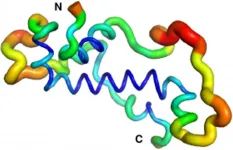

Proteins are the key component in all modern forms of life. Haemoglobin, for example, transports the oxygen in our blood; photosynthesis proteins in the leaves of plants convert sunlight into energy; and fungal enzymes help us to brew beer and bake bread. Researchers have long been examining the question of how proteins mutate or come into existence in the course of millennia. That completely new proteins - and, with them, new properties - can emerge practically out of nothing, was inconceivable for decades, in line with what the Greek philosopher Parmenides said: "Nothing can emerge from nothing" (ex nihilo nihil fit). Working with colleagues from the USA and ...