TU Graz researchers identify chemical processes as key to understanding landslides

2021-03-18

(Press-News.org) Mass movements such as landslides and hill-slope debris flows cause billions of euros in economic damage around the world every year. Between 20 and 80 million euros are spent annually from the disaster fund to repair disaster damage in Austria, 15 to 50 percent of which is attributable to mud flows and landslides. Now, a team of geologists from Graz University of Technology (TU Graz), in cooperation with the Burgenland state road administration, identified for the first time the chemical influencing factors and triggers for recurrent mass movements in fine-grained sediments. From results published in the journal Science of the Total Environment, preventive measures and strategies can be derived to guard against such events.

Factors favouring mass movements

The basis for the investigations is a well-documented landslide in southern Burgenland, which has occupied the local state road administration for four decades now. Through analysis of terrain data, soil samples, drainage waters, and laboratory tests, it has been shown that the sensitivity of the subsurface to external influences is favoured by natural (geogenic) chemical weathering processes that take place over long periods of the Earth's history and define or weaken the nature of the subsurface. On the other hand, man-made (anthropogenic) chemical influencing factors also play a central role, such as agricultural activities, seeping road run-off or winter road maintenance. "In the study area, fine-grained sedimentary deposits dominate, as they are widespread in the basin areas in eastern Austria," says Volker Reinprecht, co-author of the study and geologist at the Office of the State Government of Burgenland. "Heavy rain events and periods of dew, as well as continuous vibration from road traffic, have in the past caused the soil to literally 'wash away' and the affected road to require periodic rehabilitation."

Focus on soil drainage and the overall system

A decisive improvement of the situation was achieved by adapting the drainage system. The previous drainage system using transverse ribs, in which rainwater and seepage is captured in the area in contact with the sliding surface, was replaced by a longitudinal drainage system so that the water is removed from the subsoil within a few days and both backwater and chemical interaction processes are prevented. "Rapid drainage of the water reduces the soaking of the subsoil, reduces the formation of zones of weakness (sliding horizons) and thus increases the stability of the soil or the overall system," explains Andre Baldermann from the Institute of Applied Geosciences at TU Graz and head of the study. The geoscientist already sees the new drainage system as a first measure to prevent mass movements. "We were able to demonstrate that backwater formation in the subsurface can activate the slip zones via chemical processes. This is prevented with longitudinal drainage and the resulting faster drainage." Baldermann recommends that in future construction projects in zones at risk from sink holes, landslides or similar events, greater consideration be given to possible interactions between the drainage system and the subsoil as early as the planning stage."

Further similar studies in progress

Andre Baldermann and Volker Reinprecht are currently working on extending the study design (see additional information "investigation methods used") to other affected regions with similar geological conditions. A view of the total system is important, explains Baldermann, because: "The structure of the subsurface, as well as other region-specific factors, has a major influence on the nature, intensity, and periodicity of mass movements. The results and practical recommendations from the reference project are therefore not transferable one-to-one to other affected regions. But they are a first example of how to approach such problems in the future."

INFORMATION:

This research area is anchored in the Field of Expertise "Advanced Materials Science", one of five strategic foci of TU Graz. The work was supported by the NAWI Graz Geocenter.

Investigation methods used:

Creation of a digital terrain model to dimension the area of influence of the mass movement

Site inspections with regular sampling and core drilling in the affected areas

Characterization of the subsurface using X-ray diffraction, electron microscopy and (hydro)geochemical methods

Ion-exchange experiments to detect stabilization or destabilization phases of soil

Publication

Andre Baldermann, Martin Dietzel, Volker Reinprecht: Chemical weathering and progressing alteration as possible controlling factors for creeping landslides

Science of The Total Environment, Volume 778, 2021,

DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146300

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-18

Lenexa, Kan. -- The Infusion Nurses Society has expanded its guidance on the use of needleless connectors to include anti-reflux technology in its recently published 2021 Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice, according to Nexus Medical, makers of the Nexus TKO®-6P Anti-Reflux connector.

As INS' most recognized publication, the updated Standards outline specific categories of needleless connector technology based on the device's internal mechanism for fluid displacement -- negative displacement, positive displacement, neutral and anti-reflux. Of all the categories, the authors note that anti-reflux needleless connectors cause the least amount of blood reflux, which can ...

2021-03-17

A groundbreaking new study led by University of Minnesota Twin Cities researchers from both the College of Science and Engineering and the Medical School shows for the first time that lab-created heart valves implanted in young lambs for a year were capable of growth within the recipient. The valves also showed reduced calcification and improved blood flow function compared to animal-derived valves currently used when tested in the same growing lamb model.

If confirmed in humans, these new heart valves could prevent the need for repeated valve replacement surgeries in thousands of children born each year with congenital heart defects. The valves can also be stored for at least six months, which means they could provide surgeons with an "off the shelf" option for treatment.

The ...

2021-03-17

A long noncoding RNA whose function was previously unknown turns out to play a vital role in mobilizing the immune response following a bone marrow transplant or solid organ transplantation.

This RNA molecule, cataloged in scientific databases simply as Linc00402, helps activate immune defenders known as T cells in response to the presence of foreign human cells, according to a new study by researchers at the University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center and Michigan Medicine.

The investigation, which included samples from more than 50 patients who underwent a bone marrow or heart transplant, suggests inhibiting ...

2021-03-17

MEMPHIS, Tenn. - Non-Hispanic black patients with Type 1 diabetes and COVID-19 were almost four times as likely to present to the hospital with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) compared to non-Hispanic whites, according to an article published in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism by Le Bonheur Pediatric Endocrinologist Kathryn Sumpter, MD.

The study examined 180 patients with Type 1 diabetes and laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 from 52 clinical sites, including Le Bonheur Children's. The objective of the study was to evaluate instances of DKA, a serious complication of Type 1 diabetes, in patients with Type 1 diabetes and COVID-19 and determine if minorities had increased ...

2021-03-17

ITHACA, N.Y. - If you want to build a fully functional nanosized robot, you need to incorporate a host of capabilities, from complicated electronic circuits and photovoltaics to sensors and antennas.

But just as importantly, if you want your robot to move, you need it to be able to bend.

Cornell researchers have created micron-sized shape memory actuators that enable atomically thin two-dimensional materials to fold themselves into 3D configurations. All they require is a quick jolt of voltage. And once the material is bent, it holds its shape - even after the voltage is removed.

As a demonstration, the team created what ...

2021-03-17

The coronavirus' structure is an all-too-familiar image, with its densely packed surface receptors resembling a thorny crown. These spike-like proteins latch onto healthy cells and trigger the invasion of viral RNA. While the virus' geometry and infection strategy is generally understood, little is known about its physical integrity.

A new study by researchers in MIT's Department of Mechanical Engineering suggests that coronaviruses may be vulnerable to ultrasound vibrations, within the frequencies used in medical diagnostic imaging.

Through computer simulations, the team has modeled the virus' mechanical response to vibrations across a range of ultrasound ...

2021-03-17

A new study has found that about 35% of Americans with a cancer history had an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease in the next decade, compared with about 23% of those who didn't have cancer.

Based on a risk calculator that estimates a person's 10-year chances of developing heart disease or stroke, researchers from The Ohio State University found that the average estimated 10-year risk for a cancer survivor was about 8%, compared to 5% for those who didn't have a history of cancer.

The new study appears in the journal PLOS ONE.

"We know that obesity, cancer and cardiovascular disease share some common risk factors, and in addition to those shared risk factors, cancer patients also receive treatments including radiation and chemotherapy that can affect their cardiovascular ...

2021-03-17

Many people have never heard of Brucellosis, but farmers and ranchers in the United States forced to cull animals that test positive for the disease and people infected by the animal-transmitted Brucella abortus (B. abortus) pathogen that suffer chronic, Malaria-type symptoms, certainly have.

Brucellosis is an agricultural and human health concern on a global scale. It was introduced over 100 years ago to Bison and elk in Yellowstone National Park by cattle and has been circulating among the wild herds ever since, leading to periodic outbreaks and reinfection. There is no vaccine for humans, and experimental studies ...

2021-03-17

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (March 16, 2021) -- Older age at the time of conception and alcohol consumption during pregnancy have long been known to impact fetal development.

Now, a new report published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests older age and alcohol consumption in the year leading up to conception also may have an impact by epigenetically altering a specific gene during development of human eggs, or oocytes.

Although the study did not determine the ultimate physical effects of this change, it provides important insights into the intricate relationship between environmental exposures, genetic regulation and human development.

"While the outcome of the change isn't clear, our findings give us a valuable look into ...

2021-03-17

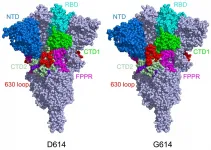

BOSTON - March 16, 2021 - The fast-spreading UK, South Africa, and Brazil coronavirus variants are raising both concerns and questions about whether COVID-19 vaccines will protect against them. New work led by Bing Chen, PhD, at Boston Children's Hospital analyzed how the structure of the coronavirus spike proteins changes with the D614G mutation -- carried by all three variants -- and showed why these variants are able to spread more quickly. The team reports its findings in Science (March 16, 2020).

Chen's team imaged the spikes with cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] TU Graz researchers identify chemical processes as key to understanding landslides