(Press-News.org) Social deficits attract so much attention in the study of autism spectrum disorder, it's easy to forget there are motor learning deficits during early childhood as well. For autistic kids hoping to throw a ball around the schoolyard and connect with classmates, these physical skill differences can isolate a child further.

In a new study published in Nature Neuroscience, researchers from the University of Ottawa's Faculty of Medicine have closed in on the neurological underpinnings of the motor learning delay.

Dr. Simon Chen's lab in the Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine of the Faculty of Medicine used a mouse model of autism to demonstrate a shortage in the amount of the neurotransmitter noradrenaline being released into the brain's primary motor cortex. Dr. Chen's lab identified the problem originating some distance away in an area of the hindbrain called the locus coeruleus, which is known as a center of motivation, alertness, and attention.

What is the locus coeruleus?

"The locus coeruleus is the area in the brain that releases noradrenaline - or adrenaline - which makes you more alert. In the mouse model of autism, we found that in the motor cortex there is a lack of adrenaline's innervation to the area which caused them to have delayed motor learning. The lack of basal level of adrenaline in the cortex causes them to have this delayed learning."

By delay in learning you mean it takes them longer to learn a task?

"Yes, and the implication is similar for kids with autism. They normally behave the same whether reaching to grab something or playing ball or catch - they learn at a slower pace compared to kids of the same age, which could cause them to feel more distant and perhaps prefer not to play with them.

"With autistic kids, we sometimes think that an aspect of this delayed motor learning is a result of social deficits and dysfunction: that they simply don't want to play with the other kids. But it might be because they're learning how to play these games slower than the other kids, which is why they're distancing themselves from them.

"We asked: what is the source of this? Is it occurring because of deficits in the locus coeruleus, or is the cause purely in the motor cortex?"

How did you proceed?

"My background is studying the mechanism in the brain involved in motor learning. I thought it would be important to investigate disorders associated with motor learning. In my literature research, I found many cases of autistic kids displaying this type of delayed motor learning. So, we thought to try to see whether we can find that in mice.

"We performed live imaging into mice's brains, and we found the brains of the adolescent mice we used showed a delay in removing old substrates while forming new ones which causes confusion to the brain causing an effect we describe as low signal-to-noise ratio (old memories are noise). When you are not removing the unnecessary synapses (old memories) you have higher noise, and we think the brain doesn't know what signal to process because of its delay of removing the unnecessary synapses. So, the mouse is slower learning what the right movement is.

"Think of it as you and I go play golf and we hit the ball many times. With a good signal-to-noise ratio in the brain, I will remember the movement when I hit the ball far. But if I have high noise and low signal-to-noise ratio, I'll hit the ball many times without knowing which movement is good for me, meaning it will take me longer to differentiate what's the right movement for a good golf swing."

What did you have the mice do to discover this?

"Mice like to run so we had them learning how to run on a spinning disk. Their head was fixed so they needed to learn how to adjust their body to run and that's what we were trying to measure. Initially, they had a hard time controlling their body position. But after 12 days, they learned how to control their body and are now able to run smoothly on the rotating disk.

"When we injected an artificial drug in the belly to increase the noradrenaline release globally, the mice's behavior was rescued. But then we asked ourselves 'how do we know it's not just because the mouse is paying more attention when they are doing the task and that's why they do it faster?' We then injected the artificial drug locally in the motor cortex to activate the axons of the axons from locus coeruleus, and the mice's behavior was again rescued.

"This suggests that it's not because the mouse is more focused but, rather, because of the drug that they learn the task better. The noradrenaline is lacking in the motor cortex and if we supplement enough noradrenaline in the motor cortex, then the mouse will be able to learn."

What should we take away from your study?

"Kids with autism tend to show a delay in motor learning which is normally overlooked since it is put down to social deficits. But it could be they are learning how to play but slower. Now it's about whether we can help the kids to learn these motor skills faster to compensate for some of the social deficits we think they're having.

"The mouse's motor skills improved quicker by boosting the noradrenaline in the motor cortex; maybe one day we can find a treatment to boost the noradrenaline in a patient and that will also help them learn a new motor skill quicker."

INFORMATION:

Though 40 million concussions are recorded annually, no effective treatment exists for them or for many other brain-related illnesses. In collaboration with Dragan Maric of the National Institutes of Health, Badri Roysam, Hugh Roy and Lillie Cranz Cullen University Professor and Chair of Electrical and Computer Engineering, and his team are working to speed up drug development to treat brain diseases and injuries like concussion by developing new tools.

"We are interested in mapping and profiling unhealthy and drug-treated brain tissue in unprecedented detail to reveal multiple biological processes at once - in context," said Roysam about his latest paper published ...

NEW YORK, NY (March 22, 2021)--The first year of the COVID-19 pandemic has taken the lives of millions of people around the world but has also left hundreds with lingering symptoms or completely new symptoms weeks after recovery.

Much is unknown about what causes these symptoms and how long they last. But with nearly 740,000 cases of COVID reported in New York City since last March--and 28 million in the United States--physicians are increasingly seeing these "long-haulers" in their practices.

"Over the course of the summer, we started getting a sense of what issues these people were having," ...

Organoids are tiny three-dimensional cellular assemblies that are grown in a laboratory from tissue-specific cells. They are particularly interesting to biologists because of their ability to mimic the characteristics of the original tissues. If scientists extract cells from a tumor, then they can grow cancer organoids that mimic the characteristics of the source tumor.

This possibility for individual-level studies of tumor properties makes cancer organoids an exciting tool from the perspective of an emerging field called precision cancer medicine. Daniel Gil of the University of Wisconsin ...

CLEVELAND--A new technique for sampling and testing cells from Barrett's esophagus (BE) patients could result in earlier and easier identification of patients whose disease has progressed toward cancer or whose disease is at high risk of progressing toward cancer, according to a collaborative study by investigators at Case Western Reserve University and Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center (JHKCC).

Published in the journal Gastroenterology, the findings show the combination of esophageal "brushing" with a massively parallel sequencing method can provide an accurate assessment of the ...

For something we spend one-third of our lives doing, we still understand remarkably little about how sleep works -- for example, why can some people sleep deeply through any disturbance, while others regularly toss and turn for hours each night? And why do we all seem to need a different amount of sleep to feel rested?

For decades, scientists have looked to the behavior of the brain's neurons to understand the nature of slumber. Now, though, researchers at UC San Francisco have confirmed that a different type of brain cell that has received far less study -- astrocytes, named for their star-like shape -- can influence how long and how deeply animals sleep. The findings could open new avenues for exploring sleep disorder therapies and help scientists better understand brain diseases linked ...

A large study of brain MRI scans from 11,679 nine- and ten-year-old children reviewed by UC San Francisco neuroradiologists identified potentially life-threatening conditions in 1 in 500 children, and more minor but possibly clinically significant brain abnormalities in 1 out of 25 children.

The results provide the best estimates to date of the true incidence of various structural abnormalities in the developing brain, and raise the question of whether all MRI brain imaging obtained during research studies should be reviewed by board-certified radiologists, as was done in this study, in the hopes of saving lives and alerting participants to incidental findings that ought to be medically evaluated.

One ...

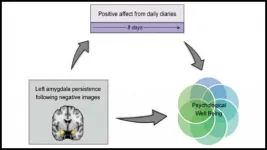

How the amygdala responds to viewing negative and subsequent neutral stimuli may impact our daily mood, according to new research published in JNeurosci.

The amygdala evaluates the environment to find potential threats. If a threat does appear, the amygdala can stay active and respond to new stimuli like they are threatening too. This is helpful when you are in a dangerous situation, but less so when spilling your coffee in the morning keeps you on edge for the rest of the day.

In a recent study, Puccetti et al. examined data collected from the "Midlife ...

MINNEAPOLIS/ST.PAUL (03/22/2021) -- New research from the University of Minnesota Medical School suggests that disease-driving B cells, a white blood cell, play a role in the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) - the most common chronic liver condition in the U.S. Their findings could lead to targeted therapies for NAFLD, which currently affects a quarter of the nation and has no FDA-approved treatments.

After noticing that patients with the disease showed a large number of inflammatory B cells in their livers, Xavier Revelo, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Integrative Biology and Physiology and senior author, began studying B cells in NAFLD.

"This disease is increasing in prevalence ...

Although Tuberculosis, or TB, killed nearly as many people as COVID-19 (approx. 1.8 million) in 2020, it did not receive as much media and public attention. The pandemic has proven that transmissible infection is indeed a global issue. TB remains a serious public health concern in Ireland, particularly with the presence of multi-drug resistant types and the numbers of complex cases here continuing to rise, with cases numbering over 300 annually.

Science tells us that iron is crucial for daily human function, but it is also an essential element for the survival of ...

Batteries charge and recharge--apparently all thanks to a perfect interplay of electrode material and electrolyte. However, for ideal battery function, the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) plays a crucial role. Materials scientists have now studied nucleation and growth of this layer in atomic detail. According to the study published in the journal Angewandte Chemie, the properties of anions and solvent molecules need to be well balanced.

In lithium-ion batteries, the SEI forms at the beginning of the first charging process, when a potential is applied. Elements from the electrolyte deposit on the graphite electrode and form a coating that soon ...