(Press-News.org) CLEVELAND--A new technique for sampling and testing cells from Barrett's esophagus (BE) patients could result in earlier and easier identification of patients whose disease has progressed toward cancer or whose disease is at high risk of progressing toward cancer, according to a collaborative study by investigators at Case Western Reserve University and Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center (JHKCC).

Published in the journal Gastroenterology, the findings show the combination of esophageal "brushing" with a massively parallel sequencing method can provide an accurate assessment of the stages of BE in patients and detect specific chromosomal alterations, including the presence of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC).

This combined approach aims to provide a practical and sensitive molecular-based method that could improve how doctors detect early progression of BE toward cancer and also assess the risks for such progression among patients already diagnosed with early-stage BE.

"The tests that we have for detecting disease progression in patients with BE are inadequate, as shown by BE patients who develop cancer while under medical surveillance," said Amitabh Chak, senior and corresponding author on the study and a professor of medicine at the School of Medicine and gastroenterologist at the University Hospitals Digestive Health Institute. "We also lack accurate means to recognize new BE patients who are at highest risk to progress toward cancer, and who need more intense surveillance."

"Our findings provide the technical means and conceptual basis for an new molecular based approach that could become key to the clinical management of this disease," said Sanford Markowitz, co-corresponding author, and the Ingalls Professor of Cancer Genetics and Medicine and Distinguished University Professor at the Case Western Reserve School of Medicine and Case Comprehensive Cancer Center (Case CCC), an oncologist at UH Seidman Cancer Center and corresponding author of the study.

Associated with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease, BE usually emerges from damage to the lining of the esophagus after repeated exposure to acid and contents from the stomach.

BE is the precursor lesion to esophageal cancer, and while most BE cases do not progress to cancer, those in whom cancer develops face an overall five-year survival rate below 20%.

Challenges in caring for BE patients are therefore to detect small areas within the BE in which progression toward cancer has occurred and to identify new BE patients in whom the risk of such progression is particularly high. This study reported a new molecular based approach that addresses both these needs.

New way to monitor BE

The effectiveness of the new approach comes from the respective convenience and effectiveness of its two parts.

First, esophageal brushings can sample a more extensive region of the esophagus than conventionally employed biopsies--even when multiple biopsies are performed. Second, massively parallel sequencing can detect chromosomal changes indicative of disease progression even in rare cells present in the mixture collected by brushings. The sequencing technology, called RealSeqS, is similar to that which JHKCC investigators developed for use in blood tests for cancer, except the Case Western Reserve and JHKCC collaborative team applied it to esophageal brushings.

"We reasoned that RealSeqS could be effective when applied to esophageal brushings, because of the underlying challenge is the same as in blood samples, that of detecting DNA from rare abnormal cells among the large number of normal cells also present," Markowitz said. More studies will be needed with larger cohorts to refine the approach, he said.

Current BE testing and monitoring methods, including endoscopic detection surveillance and testing of abnormal tissue, to monitor BE for progression and to detect esophageal cancer, but the approach relies on the sampling with random biopsies, which are inherently imprecise.

"This new method shows promise to make the monitoring of BE more efficient and effective," said Chak. "Currently, some patients can progress to advanced cancer even though they are under surveillance. Most patients are not at risk for progressing, yet because we cannot tell who is not at risk for progressing, we survey everyone--so we over-survey patients. We are seeking to change this."

In the study, esophageal brushings were obtained from patients without BE, with early-stage BE--known as non-dysplastic BE (NDBE); with earliest-stage progression, known as low-grade dysplasia (LGD); with further progression known as high grade dysplasia (HGD), or with full progression to EAC.

Testing esophageal brushing samples with RealSeqS, enabled researchers to develop molecular classifiers--based on detecting progression associated chromosome alterations contributed by rare cells in the BE--to accurately discriminate between patients with non-dysplastic BE (NDBE) and those with precancerous cells (dysplasia) or cancer. Moreover, the investigators identified a unique subset of 7% of NDBE patients who already showed the molecular signature of its progression, and who are likely to be at high risk of developing clinically evident progressive disease.

INFORMATION:

The study is a collaboration between JHKCC and the Case CCC's GI SPORE (Gastrointestinal Specialized Program of Research Excellence) and BETRNet (Barrett's Esophagus Translational Research Network) programs led respectively by Markowitz, Chak, and Joseph Willis, a pathology professor at the School of Medicine and pathology vice-chair for translational research at UH.

Co-authors of the paper "Massively Parallel Sequencing of Esophageal Brushings Enables an Aneuploidy-Based Classification of Patients with Barrett's Esophagus," include joint first authors Christopher Douville of the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) and Helen R. Moinova from Case Western Reserve (CWRU); joint senior authors Chetan Bettegowda of JHU and Willis and Chak of CWRU/UH; additional authors include Prashanthi N. Thota of Cleveland Clinic; Nicholas J. Shaheen of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine; Prasad G. Iyer of Mayo Clinic; Jean S. Wang of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis; John Dumot and Ashley Faulx of UH; and Kenneth W. Kinzler, Marcia Irene Canto, Nickolas Papadopoulos and Bert Vogelstein of JHU.

For something we spend one-third of our lives doing, we still understand remarkably little about how sleep works -- for example, why can some people sleep deeply through any disturbance, while others regularly toss and turn for hours each night? And why do we all seem to need a different amount of sleep to feel rested?

For decades, scientists have looked to the behavior of the brain's neurons to understand the nature of slumber. Now, though, researchers at UC San Francisco have confirmed that a different type of brain cell that has received far less study -- astrocytes, named for their star-like shape -- can influence how long and how deeply animals sleep. The findings could open new avenues for exploring sleep disorder therapies and help scientists better understand brain diseases linked ...

A large study of brain MRI scans from 11,679 nine- and ten-year-old children reviewed by UC San Francisco neuroradiologists identified potentially life-threatening conditions in 1 in 500 children, and more minor but possibly clinically significant brain abnormalities in 1 out of 25 children.

The results provide the best estimates to date of the true incidence of various structural abnormalities in the developing brain, and raise the question of whether all MRI brain imaging obtained during research studies should be reviewed by board-certified radiologists, as was done in this study, in the hopes of saving lives and alerting participants to incidental findings that ought to be medically evaluated.

One ...

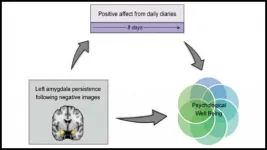

How the amygdala responds to viewing negative and subsequent neutral stimuli may impact our daily mood, according to new research published in JNeurosci.

The amygdala evaluates the environment to find potential threats. If a threat does appear, the amygdala can stay active and respond to new stimuli like they are threatening too. This is helpful when you are in a dangerous situation, but less so when spilling your coffee in the morning keeps you on edge for the rest of the day.

In a recent study, Puccetti et al. examined data collected from the "Midlife ...

MINNEAPOLIS/ST.PAUL (03/22/2021) -- New research from the University of Minnesota Medical School suggests that disease-driving B cells, a white blood cell, play a role in the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) - the most common chronic liver condition in the U.S. Their findings could lead to targeted therapies for NAFLD, which currently affects a quarter of the nation and has no FDA-approved treatments.

After noticing that patients with the disease showed a large number of inflammatory B cells in their livers, Xavier Revelo, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Integrative Biology and Physiology and senior author, began studying B cells in NAFLD.

"This disease is increasing in prevalence ...

Although Tuberculosis, or TB, killed nearly as many people as COVID-19 (approx. 1.8 million) in 2020, it did not receive as much media and public attention. The pandemic has proven that transmissible infection is indeed a global issue. TB remains a serious public health concern in Ireland, particularly with the presence of multi-drug resistant types and the numbers of complex cases here continuing to rise, with cases numbering over 300 annually.

Science tells us that iron is crucial for daily human function, but it is also an essential element for the survival of ...

Batteries charge and recharge--apparently all thanks to a perfect interplay of electrode material and electrolyte. However, for ideal battery function, the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) plays a crucial role. Materials scientists have now studied nucleation and growth of this layer in atomic detail. According to the study published in the journal Angewandte Chemie, the properties of anions and solvent molecules need to be well balanced.

In lithium-ion batteries, the SEI forms at the beginning of the first charging process, when a potential is applied. Elements from the electrolyte deposit on the graphite electrode and form a coating that soon ...

Antibiotics have revolutionized the field of medicine by making it possible to treat most known microbial diseases today. However, their uncontrolled usage has led to the major global problem of antibiotic resistance. As we continue to exploit antibiotics, sometimes at doses much higher than needed, disease-causing bacteria are rapidly evolving defense strategies to evade them. These drug-resistant bacteria, also known as "superbugs," cause severe infections that are difficult to treat and can eventually be fatal.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a particularly vicious group of superbugs that have developed resistance to the antibiotic methicillin, is a major cause of hospital-acquired infections. Accurate and timely diagnosis ...

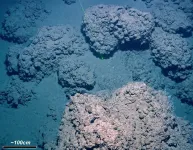

Boulder, Colo., USA: Beneath the cold, dark depths of the Arctic ocean sit vast reserves of methane. These stores rest in a delicate balance, stable as a solid called methane hydrates, at very specific pressures and temperatures. If that balance gets tipped, the methane can get released into the water above and eventually make its way to the atmosphere. In its gaseous form, methane is one of the most potent greenhouse gases, warming the Earth about 30 times more efficiently than carbon dioxide. Understanding possible sources of atmospheric methane is critical for accurately predicting future climate change.

In the Arctic Ocean today, ice sheets exert pressure on the ground below them. That pressure diffuses ...

Screenings for breast cancer and colon cancer dropped dramatically during the early months of the coronavirus pandemic, but use of the procedures returned to near-normal levels by the end of July 2020, according to a new study.

Analyzing insurance claims from more than 6 million Americans with private health coverage, researchers found that mammography rates among women aged 45 to 64 declined by 96% during March and April 2020 as compared to January and February.

Similarly, the weekly rate of colorectal cancer screenings among adults aged 45 to 64 and older declined by 95% during the period.

By the end of July 2020, however, the rate of mammograms among women had rebounded and was slightly higher than it had been before the pandemic was declared. The rate of colonoscopies also rebounded, ...

Researchers at Trinity College Dublin have been shedding light on the enigmatic "spiders from Mars", providing the first physical evidence that these unique features on the planet's surface can be formed by the sublimation of CO2 ice.

Spiders, more formally referred to as araneiforms, are strange-looking negative topography radial systems of dendritic troughs; patterns that resemble branches of a tree or fork lightning. These features, which are not found on Earth, are believed to be carved into the Martian surface by dry ice changing directly from solid to gas (sublimating) in the spring. Unlike Earth, Mars' atmosphere comprises mainly of CO2 and as temperatures decrease in winter, this deposits onto the surface as CO2 ...