(Press-News.org) Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere fuels plant growth. As carbon levels rise, it's appealing to think of supercharged plant growth and massive tree-planting campaigns drawing down the CO2 produced by fossil fuel burning, agriculture and other human activities.

New research published March 24 in Nature, however, suggests that when elevated carbon dioxide levels drive increased plant growth, it takes a surprisingly steep toll on another big carbon sink: the soil.

One likely explanation, the authors say, is that plants effectively mine the soil for nutrients they need to keep up with carbon-fueled growth. Extracting the extra nutrients requires revving up microbial activity, which then releases CO2 into the atmosphere that might otherwise remain locked in soil.

The findings contradict a widely accepted assumption that biomass and soil carbon will increase in tandem as more plant biomass falls to the ground and turns into organic matter. By analyzing data from 108 previously published experiments dealing with soil carbon levels, plant growth and high concentrations of CO2 in the air, the authors were surprised to find the opposite.

"When plants increase biomass, usually there's a decrease in soil carbon storage," said lead author César Terrer, a fellow at Lawrence Livermore National Lab who worked on the research as a postdoctoral scholar at Stanford University.

Terrer and colleagues found soils only accumulated more carbon in experiments where plant growth remained fairly steady despite high levels of carbon in the atmosphere. "It proved much harder than expected to increase both plant growth and soil carbon," said senior study author Rob Jackson, a professor of Earth system science in Stanford's School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth).

Widely used climate projections today don't account for this tradeoff, Jackson said. As a result, they likely overestimate the potential of land to draw down carbon dioxide from Earth's atmosphere.

Plants and soils together currently absorb an estimated 30 percent of the CO2 emitted by human activities each year. Predicting how the underground portion of this carbon sink will change in the coming decades is especially important because carbon absorbed by soil tends to stay there for a long time. "When a plant dies, some of the carbon that accumulated in its biomass may return to the atmosphere. In soils, carbon can be stored for centuries or millennia," Terrer explained.

The work builds on research Terrer, Jackson and colleagues published in 2019 estimating that a doubling of atmospheric CO2 from pre-industrial levels - as expected by the end of this century - will increase plant biomass by only about 12 percent. In other words, plants will likely play a far less significant role in drawing down carbon than previously predicted.

Now, by examining how carbon storage works in plants and soils together, the scientists have found that expectations for another piece of the climate puzzle also need to be revised. "Soils store more carbon worldwide than is contained in all plant biomass. They need much more attention as we project the fate of forests and grasslands to the changing atmosphere," said Jackson, who is also a senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

The research suggests grasslands may absorb unexpectedly large amounts of carbon in the coming decades. Under a scenario where atmospheric CO2 doubles pre-industrial levels the researchers estimate carbon uptake in grassland soils will increase 8 percent, while carbon uptake by forest soils will remain roughly flat. That's in spite of CO2 enrichment giving a greater boost to biomass in forests (23 percent) than in grasslands (9 percent), partly because trees allocate belowground a relatively small portion of the carbon they absorb.

"From a biodiversity point of view, it would be a mistake to plant trees in natural grassland and savanna ecosystems," Terrer said. "Our results suggest these grassy ecosystems with very few trees are also important for storing carbon in soil."

INFORMATION:

Rob Jackson is the Michelle and Kevin Douglas Provostial Professor at Stanford Earth. Coauthors are affiliated with Indiana University, Bloomington; Northern Arizona University; Oak Ridge National Lab; University of Exeter; University of California, Berkeley; Lawrence Berkeley National Lab; ETH Zurich; Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research WSL; University of Minnesota, St. Paul; Western Sydney University; University of Cambridge; University of Oxford; Washington State University; California Institute of Technology; University of California, Los Angeles; and University of Antwerp.

The research was supported by Lawrence Livermore National Lab, the U.S. Department of Energy, California Institute of Technology and NASA.

The secret to building superconducting quantum computers with massive processing power may be an ordinary telecommunications technology - optical fiber.

Physicists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have measured and controlled a superconducting quantum bit (qubit) using light-conducting fiber instead of metal electrical wires, paving the way to packing a million qubits into a quantum computer rather than just a few thousand. The demonstration is described in the March 25 issue of Nature.

Superconducting circuits are a leading technology for making quantum computers because they are reliable and easily mass produced. But these circuits must operate at cryogenic temperatures, and schemes for wiring them to room-temperature electronics are complex and prone to ...

As the signs of today's human-caused climate change become ever more alarming, research into the ways past societies responded to natural climate changes is growing increasingly urgent. Scholars have often argued that climatic changes plunge communities into crisis and provide the conditions that lead societies to collapse, but a growing body of research shows that the impacts of climate change on past populations are rarely so straightforward.

In a new paper published in Nature, scholars in archaeology, geography, history and paleoclimatology present a framework for research into what they term 'the History of Climate and Society' (HCS). The framework uses a series of ...

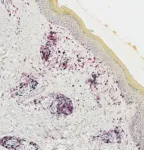

LEBANON, NH - Some melanoma patients respond very well to immunotherapy, experiencing profound and durable tumor regression. A fraction of these patients will also develop autoimmunity against their normal melanocytes--the cells that give rise to melanoma--a phenomenon called vitiligo. Melanoma survivors with vitiligo have long been recognized as a special group with an outstanding prognosis, and a strong response of immune system cells called T cells.

Immunotherapy researchers at Dartmouth's and Dartmouth-Hitchcock's Norris Cotton Cancer Center (NCCC) led by Mary Jo Turk, PhD, and surgical oncologist Christina Angeles, MD (now of University of Michigan), have discovered how a subset ...

The ocean is dynamic in nature, playing a crucial role as a planetary thermostat that buffer global warming. However, in response to climate change, the ocean has generally become stabler over the past 50 years. Six times stabler, in fact, than previously estimated--as shown by a new study that researchers from the CNRS, Sorbonne University, and IFREMER have conducted within the scope of an international collaboration.* Warming waters, melting glaciers, and disrupted precipitation patterns have created an ocean surface layer cut off from the depths. Just as oil and ...

Training babies' brains and bodies might delay the onset of Rett syndrome, a devastating neurological disorder that affects about 1 in 10,000 girls worldwide.

In experiments with mice that replicate the genetic disorder, scientists discovered that intense behavioral training before symptoms develop staves off both memory loss and motor control decline. Compared to untrained mice, those trained early in life were up to five times better at performing tasks that tested their coordination or their ability to learn, Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator Huda Zoghbi and her colleagues report March 24, 2021, in the journal Nature.

Those data, from animals whose symptoms closely mimic the human disease, offers a clear rationale for genetically screening newborns for Rett syndrome, ...

New York, NY (March 24, 2021) -- Immunotherapy is not only significantly less effective in liver cancer patients who previously had a liver disease called non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), but actually appears to fuel tumor growth, according to a Mount Sinai study published in Nature in March. NASH affects as many as 40 million people worldwide and is associated with obesity and diabetes.

The researchers led a large international collaboration to investigate immunotherapy's effect on hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), a deadly liver cancer, caused by NASH. They conducted a meta-analysis ...

New scientific findings bring hope that early training during the presymptomatic phase could help individuals with Rett syndrome, a neurodevelopmental disorder, retain specific motor and memory skills and delay the onset of the condition. Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine and the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute at Texas Children's Hospital reported in the journal Nature that, in a mouse model of Rett syndrome, intensive training beginning before symptoms appear dramatically improved the performance of specific motor and memory tasks and substantially delayed the appearance of symptoms.

The researchers propose that newborn genetic testing for Rett syndrome, followed by prompt intensive training in the skills that will be affected, such ...

Immunotherapy using checkpoint inhibitors is effective in around a quarter of patients with liver cancer. However, to date, physicians have been unable to predict which patients would benefit from this type of treatment and which would not. Researchers from the German Cancer Research Center have now discovered that liver cancer caused by chronic inflammatory fatty liver disease does not respond to this treatment. On the contrary: in an experimental model, this type of immunotherapy actually promoted the development of liver cancer, as now reported in the journal Nature.

Liver cancer is the sixth most common type of cancer in the world, ...

The heart of any computer, its central processing unit, is built using semiconductor technology, which is capable of putting billions of transistors onto a single chip. Now, researchers from the group of Menno Veldhorst at QuTech, a collaboration between TU Delft and TNO, have shown that this technology can be used to build a two-dimensional array of qubits to function as a quantum processor. Their work, a crucial milestone for scalable quantum technology, was published today in Nature.

Quantum computers have the potential to solve problems that are impossible to address with classical computers. Whereas current ...

HOUSTON ? Overcoming previous technical challenges with single-cell DNA (scDNA) sequencing, a group led by researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center has developed a novel method for scDNA sequencing at single-molecule resolution. This technique revealed for the first time that triple-negative breast cancers undergo continued genetic copy number changes after an initial burst of chromosome instability.

The findings, published today in Nature, offer an accurate and efficient new approach for sequencing hundreds of individual cancer cells while also providing novel insights into cancer evolution. These insights may explain why treatments are ...