(Press-News.org) NEW YORK, NY--Treatments for a rare retinal disease may be on the horizon after a new study has identified gene variants that cause a metabolic deficiency in the eye.

The disease, macular telangiectasia type 2 (MacTel), has been a research focus of Rando Allikmets, PhD, a pioneer in the genetics of eye diseases, for nearly 15 years. MacTel occurs in approximately 1 in 5,000 adults over age 40 and slowly causes a significant loss of central vision, which can impair driving, reading, and other activities.

"MacTel is clearly a genetic disease because it tends to run in families, but it's been a tough nut to crack," says Allikmets, the William and Donna Acquavella Professor of Ophthalmic Sciences in the Departments of Ophthalmology and Pathology & Cell Biology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

"For many years, we didn't know what was causing the disease, and we couldn't find any genes that would give us some clues."

That began to change a few years ago when Allikmets and an international team of MacTel researchers led by Lowy Medical Research Institute identified two extremely rare mutations that cause the disease.

These genes account for only 0.1% of cases, but their discovery, also made possible by advances in the emerging field of metabolomics, led to a new view of MacTel as a disease of serine deficiency. Serine is one of 20 amino acids that play an important role in metabolism in the eye and throughout the body.

In a landmark study published in NEJM in 2019, the team found that most MacTel patients, regardless of their genetic makeup, have a serine deficiency that leads to the accumulation of a toxic lipid that damages cells in the retina. Some degree of serine deficiency is prevalent in the general population, and some of these individuals can develop various diseases, including MacTel. However, the exact genetic cause is not known for the vast majority of cases.

PHGDH Accounts for 3% to 4% of Cases

Now the team has uncovered another gene that solidifies the link between MacTel and serine deficiency and points the way to effective treatment. Allikmets, working with David Goldstein, PhD, and the Institute of Genomic Medicine at Columbia, used a recently developed method, called collapsing analysis, that can pinpoint difficult-to-find genes.

The researchers found that mutations in the new MacTel gene, PHGDH, directly reduce serine levels by partially disabling phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase, the most important enzyme involved in serine biosynthesis.

And though PHGDH accounts for only about 3% to 4% of MacTel cases, "its identification is significant because it causes the same disease features that we see in a substantial number of patients with MacTel," Allikmets says.

"That suggests that fixing the serine deficiency or targeting the toxic lipids may be a way to prevent vision loss in many MacTel patients, regardless of the patient's precise genetic defect."

Though the MacTel field is hopeful that treatment options are not far away, Allikmets adds that new therapeutic ideas must be tested first in clinical trials and may not be available for several years.

INFORMATION:

More Information

The new study, "Serine biosynthesis defect due to haploinsufficiency of PHGDH causes retinal disease(link is external and opens in a new window)," was published March 22 in Nature Metabolism.

Authors are Kevin Eade (Lowy Medical Research Institute), Marin L. Gantner (LMRI), Joseph A. Hostyk (Columbia), Takayuki Nagasaki (Columbia), Sarah Giles (LMRI), Regis Fallon (LMRI), Sarah Harkins-Perry (LMRI and Scripps Research Institute), Michelle Baldini (UCSD), Esther W. Lim (UCSD), Lea Scheppke (LMRI), Michael I. Dorrell (LMRI), Carolyn Cai (Columbia), Evan H. Baugh (Columbia), Charles J. Wolock (Columbia), Martina Wallace (UCSD), Rebecca B. Berlow (Scripps), David B. Goldstein (Columbia), Christian M. Metallo (UCSD), Martin Friedlander (LMRI and Scripps), and Rando Allikmets (Columbia).

The research was supported by the Lowy Family; the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grants R01CA234245, R01EY028203, R01EY029315, and P30EY019007); and by funds from Research to Prevent Blindness to the Department of Ophthalmology, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Columbia University Irving Medical Center provides international leadership in basic, preclinical, and clinical research; medical and health sciences education; and patient care. The medical center trains future leaders and includes the dedicated work of many physicians, scientists, public health professionals, dentists, and nurses at the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, the Mailman School of Public Health, the College of Dental Medicine, the School of Nursing, the biomedical departments of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and allied research centers and institutions. Columbia University Irving Medical Center is home to the largest medical research enterprise in New York City and State and one of the largest faculty medical practices in the Northeast. For more information, visit cuimc.columbia.edu or columbiadoctors.org.

TAMPA, Fla. -- Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, or CAR T, is a relatively new type of therapy approved to treat several types of aggressive B cell leukemias and lymphomas. Many patients have strong responses to CAR T; however, some have only a short response and develop disease progression quickly. Unfortunately, it is not completely understood why these patients have progression. In an article published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Moffitt Cancer Center researchers use mathematical modeling to help explain why CAR T cells work in some patients and not in others.

CAR T is a type of personalized immunotherapy that uses a patient's own T ...

ORLANDO, March 25, 2021 - Early screening can mean the difference between life and death in a cancer and disease diagnosis. That's why University of Central Florida researchers are working to develop a new screening technique that's more than 300 times as effective at detecting a biomarker for diseases like cancer than current methods.

The technique, which was detailed recently in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, uses nanoparticles with nickel-rich cores and platinum-rich shells to increase the sensitivity of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

ELISA is a test ...

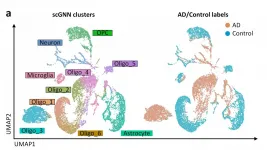

Studying genetic material on a cellular level, such as single-cell RNA-sequencing, can provide scientists with a detailed, high-resolution view of biological processes at work. This level of detail helps scientists determine the health of tissues and organs, and better understand the development of diseases such as Alzheimer's that impacts millions of people. However, a lot of data is also generated, and leads to the need for an efficient, easy-to-use way to analyze it.

Now, a team of engineers and scientists from the University of Missouri and the Ohio State University have created a new way to analyze data from single-cell RNA-sequencing ...

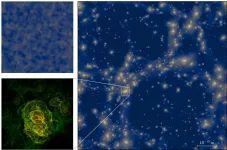

The very first moments of the Universe can be reconstructed mathematically even though they cannot be observed directly. Physicists from the Universities of Göttingen and Auckland (New Zealand) have greatly improved the ability of complex computer simulations to describe this early epoch. They discovered that a complex network of structures can form in the first trillionth of a second after the Big Bang. The behaviour of these objects mimics the distribution of galaxies in today's Universe. In contrast to today, however, these primordial structures are microscopically small. Typical clumps have masses of only a few grams and fit into volumes much smaller than present-day elementary particles. The results of the study have been published ...

One-third of the Earth's surface is covered by more than 11,000 grass species -- including crops like wheat, corn, rice and sugar cane that account for the bulk of the world's agricultural food production and important biofuels. But grass is so common that few people realize how diverse and important it really is.

Research published today in the journal Nature provides insights that scientists could use not only to improve crop design but also to more accurately model the effects of climate change. It also offers new clues that could help scientists use ...

Orthopaedic researchers are one step closer to preventing life-long arm and leg deformities from childhood fractures that do not heal properly.

A new study led by the University of South Australia and published in the journal Bone, sheds light on the role that a protein plays in this process.

Lead author Dr Michelle Su says that because children's bones are still growing, an injury to the growth plate can lead to a limb in a shortened position, compared to the unaffected side.

"Cartilage tissue near the ends of long bones is known as the growth plate that is responsible for bone growth in children and, unfortunately, 30 per cent of childhood and teen fractures involve this growth ...

Researchers have used the evidence of pumice from an underwater volcanic eruption to answer a long-standing mystery about a mass death of migrating seabirds.

New research into the mass death of millions of shearwater birds in 2013 suggests seabirds are eating non-food materials including floating pumice stones, because they are starving, potentially indicating broader health issues for the marine ecosystem.

The research which was led by CSIRO, Australia's national science agency, and QUT, was published in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series, that examined a 2013 seabird "wreck" in which up to 3 million ...

A coordinated global effort to reduce the production of greenhouse gas emissions from industry and other sectors may not stop climate change, but Earth has a powerful ally that humans might partner with to achieve carbon neutrality: Mother Nature. An international team of researchers called for the use of natural climate solutions to help "cancel" produced emissions and remove existing emissions as part of a comprehensive plan to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius -- the point at which damage to human life and livelihoods could become catastrophic, according to the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The researchers published their invited views on March 24 in ...

Recently, the team led by Professor WU Changzheng from School of Chemistry and Materials Science from University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) in cooperation with the team led by Prof. WU Hengan from School of Engineering Science, realized the homogenization of surface active sites of heterogeneous catalyst by dissolving the electrocatalytic active metal in molten gallium. The related results have been published on the Nature Catalysis on March 11th.

Due to the existence of various defects and crystal faces, the active components on the surface of heterogeneous catalysts are often in different ...

Tsukuba, Japan - Physical exercise has long been prescribed as a way to improve the quality of sleep. But now, researchers from Japan have found that even when exercise causes objectively measured changes in sleep quality, these changes may not be subjectively perceptible.

In a study published this month in Scientific Reports, researchers from the University of Tsukuba have revealed that vigorous exercise was able to modulate various sleep parameters associated with improved sleep, without affecting subjective reports regarding sleep quality.

Exercise is ...