(Press-News.org) By clearing forests, burning grasslands, plowing fields and harvesting crops, humans apply strong selective pressures on the plants that survive on the landscapes we use. Plants that evolved traits for long-distance seed-dispersal, including rapid annual growth, a lack of toxins and large seed generations, were more likely to survive on these dynamic anthropogenic landscapes. In the current article, researchers argue that these traits may have evolved as adaptations for megafaunal mutualisms, later allowing those plants to prosper among increasingly sedentary human populations.

The new study hypothesizes that the presence of specific anthropophilic traits explains why a select few plant families came to dominate the crop and weed assemblages around the globe, such as quinoa, some grasses, and knotweeds. These traits, the authors argue, also explain why so many genera appear to have been domesticated repeatedly in different parts of the world at different times. The 'weediness' and adaptability of those plants was the result of exaptation traits, or changes in the function of an evolutionary trait. In this way, rather than an active and engaged human process, certain plants gradually increased in prominence around villages, in cultivated fields, or on grazing land.

Grasses and field crops weren't the only plants to use prior adaptations to prosper in human landscapes; select handfuls of trees also had advantageous traits, such as large fleshy fruits, resulting from past relationships with large browsers. The rapid extinction of megafauna at the end of the Pleistocene left many of these large-fruiting tree species with small, isolated populations, setting the stage for more dramatic changes during later hybridization. When humans began moving these trees they were likely to hybridize with distant relatives, resulting, in some cases, in larger fruits and more robust plants. In this way, the domestication process for many long-generation perennials appears to have been more rapid and tied into population changes due to megafaunal extinctions.

"The key to better understanding plant domestication may lay further in the past than archaeologists have previously thought; we need to think about the domestication process as another step in the evolution of life on Earth, as opposed to an isolated phenomenon," states Dr. Robert Spengler. He is the director of the archaeobotanical laboratories at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany, and the lead investigator on this paper.

This publication is a result of archaeologists, geneticists, botanists, and paleontologists contributing insights from their unique disciplines to reframe the way scholars think about domestication. The goal of the collaboration is to get researchers to consider the deeper ecological legacies of the plants and the pre-cultivation adaptations that they study.

Prof. Nicole Boivin, director of the Department of Archaeology at the Max Planck Institute in Jena, studies the ecological impacts of humans deep in the past. "When we think about the ecology of the origins of agriculture, we need to recognize the dramatic changes in plant and animal dynamics that have unfolded across the Holocene, especially those directly resulting from human action," she adds.

Ultimately, the scholars suggest that, rather than in archaeological excavations, laboratories, or in modern agricultural fields, the next big discoveries in plant domestication research may come from restored megafaunal landscapes. Ongoing research by Dr. Natalie Mueller, one of the authors, on North American restored prairies is investigating potential links between bison and the North American Lost Crops. Similar studies could be conducted on restored megafaunal landscapes in Europe, such as the Bia?owieski National Park in Poland, the Ust'-Buotoma Bizon Park or Pleistocene Park in Sakha Republic, Russia.

Dr. Ashastina, another author on the paper and a paleontologist studying Pleistocene vegetation communities in North Asia, states, "these restored nature preserves provide a novel glimpse deep into the nature of plant and animal interactions and allow ecologists, not only to directly trace vegetation changes occurring under herbivore pressure in various ecosystems, but to disentangle the deeper legacies of these mutualisms."

INFORMATION:

The claim that old-growth forests play a significant role in climate mitigation, based upon the argument that even the oldest forests keep sucking CO2 out of the atmosphere, is being refuted by researchers at the University of Copenhagen. The researchers document that this argument is based upon incorrectly analysed data and that the climate mitigation effect of old and unmanaged forests has been greatly overestimated. Nevertheless, they reassert the importance of old-growth forest for biodiversity.

Old and unmanaged forest has become the subject of much debate in ...

One big challenge for the production of synthetic cells is that they must be able to divide to have offspring. In the journal Angewandte Chemie, a team from Heidelberg has now introduced a reproducible division mechanism for synthetic vesicles. It is based on osmosis and can be controlled by an enzymatic reaction or light.

Organisms cannot simply emerge from inanimate material ("abiogenesis"), cells always come from pre-existing cells. The prospect of synthetic cells newly built from the ground up is shifting this paradigm. However, one obstacle on this path is the question of controlled division--a requirement for having "progeny".

A team from the Max Planck Institute for Medical Research in Heidelberg, Heidelberg ...

The team of researchers at Kaunas University of Technology (KTU), Lithuania applied artificial intelligence (AI) methods to evaluate data of human embryo development. The AI-based system photographs the embryos every five minutes, processes the data of their development and notifies any anomalies observed. This increases the likelihood of choosing the most viable and healthy early-stage embryo for IVF procedures. The innovation was developed in collaboration with Esco Medical Technologies, a manufacturer of medical equipment.

Almost one in six couples face infertility; about 48.5 million couples, 186 million individuals worldwide are inflicted. Europe has one of the lowest birth rates in the world, with an average of just 1.55 children per woman.

The most effective form of ...

By offering a microscopic "tightrope" to cells, Virginia Tech and Johns Hopkins University researchers have brought new insights to the way migrating cells interact in the body. The researchers changed their testing environment for observing cell-cell interaction to more closely mirror the body, resulting in new observations of cells interacting like cars on a highway -- pairing up, speeding up, and passing one another.

Understanding the ways migrating cells react to one another is essential to predicting how cells change and evolve and how they react in applications, such as wound healing and drug delivery. In a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team formed by Mechanical Engineering Associate ...

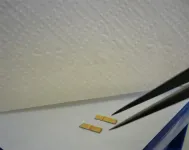

Scientists of Tomsk Polytechnic University jointly with colleagues from different countries have developed a new sensor with two layers of nanopores. In the conducted experiments, this sensor showed its efficiency as a sensor for one of the doping substances from chiral molecules. The research findings are published in Biosensors and Bioelectronics (IF: 10,257; Q1) academic journal.

The material is a thick wafer with pores of 20-30 nm in diameter. The scientists grew a layer of metal-organic frameworks (MOF) from Zn ions and organic molecules on these thick wafers. The MOF has about 3 nm nanopores only. It plays the role of a trap for molecules, which must be detected.

"This sensor can operate with chiral molecules. Such substances consisting of chiral molecules are a lot among medical ...

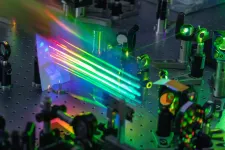

In the future, photovoltaic cells could be "worn" over clothes, placed on cars or even on beach umbrellas. These are just some of the possible developments from a study published in Nature Communications by researchers at the Physics Department of the Politecnico di Milano, working with colleagues at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg and Imperial College London.

The research includes among its authors the Institute of Photonics and Nanotechnology (IFN-CNR) researcher Franco V. A. Camargo and Professor Giulio Cerullo. It focused on photovoltaic cells made using flexible organic technology. Today's most popular photovoltaic cells, based on silicone technology, are rigid and ...

The Miscanthus genus of grasses, commonly used to add movement and texture to gardens, could quickly become the first choice for biofuel production. A new study shows these grasses can be grown in lower agricultural grade conditions - such as marginal land - due to their remarkable resilience and photosynthetic capacity at low temperatures.

Miscanthus is a promising biofuel thanks to its high biomass yield and low input requirements, which means it can adapt to a wide range of climate zones and land types. It is seen as a viable commercial option for farmers but yields ...

Energy models are used to explore different options for the development of energy systems in virtual "laboratories". Scientists have been using energy models to provide policy advice for years. As a new study shows, energy models influence policymaking around the energy transition. Similarly, policymakers influence the work of modellers. Greater transparency is needed to ensure that political considerations do not set the agenda for future research or determine its findings, the researchers demand.

Renewable energies bring many changes, including fluctuations in the energy supply and a more geographically distributed generation system. ...

A collaborative research project by team of undergraduate students from the University of Exeter's Natural Sciences department has been published in a prestigious academic journal.

Lewis Howell, Eleanor Osborne and Alice Franklin have had their second-year research published in The Journal of Physical Chemistry B.

Their paper, Pattern Recognition of Chemical Waves: Finding the Activation Energy of the Autocatalytic Step in the Belousov-Zhabotinsky Reaction, was a result of their extended experiment work in the Stage 2 module "Frontiers in Science 2".

Their project involved the Belousov-Zhabotinsky chemical reaction - an ...

March 7, 2021, KAUST, Saudi Arabia - KAUST Assistant Professor of Computer Science Mohamed Elhoseiny has developed, in collaboration with Stanford University, CA, and École Polytechnique (LIX), France, a large-scale dataset to train AI to reproduce human emotions when presented with artwork.

The resulting paper, "ArtEmis: Affective Language for Visual Art," will be presented at the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), the premier annual computer science conference, which will be held June 19-25, 2021.

Described as the "Affective Language for Visual Art," ArtEmis's user interface has seven emotional descriptions on average for each image, bringing the total count to over 439K emotional-explained attributions from humans on ...