(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON--A vast global ocean may have covered early Earth during the early Archean eon, 4 to 3.2 billion years ago, a side effect of having a hotter mantle than today, according to new research.

The new findings challenge earlier assumptions that the size of the Earth's global ocean has remained constant over time and offer clues to how its size may have changed throughout geologic time, according to the study's authors.

Most of Earth's surface water exists in the oceans. But there is a second reservoir of water deep in Earth's interior, in the form of hydrogen and oxygen attached to minerals in the mantle.

A new study in AGU Advances, which publishes high-impact, open-access research and commentary across the Earth and space sciences, estimates how much water the mantle potentially could hold today and how much water it could have stored in the past.

The findings suggest that, since early Earth was hotter than it is today, its mantle may have contained less water because mantle minerals hold onto less water at higher temperatures. Assuming that the mantle currently has more than 0.3-0.8 times the mass of the ocean, a larger surface ocean might have existed during the early Archean. At that time, the mantle was about 1,900-3,000 degrees Kelvin (2,960-4,940 degrees Fahrenheit), compared to 1,600-2,600 degrees Kelvin (2,420-4,220 degrees Fahrenheit) today.

If early Earth had a larger ocean than today, that could have altered the composition of the early atmosphere and reduced how much sunlight was reflected back into space, according to the authors. These factors would have affected the climate and the habitat that supported the first life on Earth.

"It's sometimes easy to forget that the deep interior of a planet is actually important to what's going on with the surface," said Rebecca Fischer, a mineral physicist at Harvard University and co-author of the new study. "If the mantle can only hold so much water, it's got to go somewhere else, so what's going on thousands of kilometers below the surface can have pretty big implications."

Earth's sea level has remained fairly constant during the last 541 million years. Sea levels from earlier in Earth's history are more challenging to estimate, however, because little evidence has survived from the Archean eon. Over geologic time, water can move from the surface ocean to the interior through plate tectonics, but the size of that water flux is not well understood. Because of this lack of information, scientists had assumed the global ocean size remained constant over geologic time.

In the new study, co-author Junjie Dong, a mineral physicist at Harvard University, developed a model to estimate the total amount of water that Earth's mantle could potentially store based on its temperature. He incorporated existing data on how much water different mantle minerals can store and considered which of these 23 minerals would have occurred at different depths and times in Earth's past. He and his co-authors then related those storage estimates to the volume of the surface ocean as Earth cooled.

Jun Korenaga, a geophysicist at Yale University who was not involved in the research, said this is the first time scientists have linked mineral physics data on water storage in the mantle to ocean size. "This connection has never been raised in the past," he said.

Dong and Fischer point out that their estimates of the mantle's water storage capacity carry a lot of uncertainty. For example, scientists don't fully understand how much water can be stored in bridgmanite, the main mineral in the mantle.

The new findings shed light on how the global ocean may have changed over time and can help scientists better understand the water cycles on Earth and other planets, which could be valuable for understanding where life can evolve.

"It is definitely useful to know something quantitative about the evolution of the global water budget," said Suzan van der Lee, a seismologist at Northwestern University who did not participate in the study. "I think this is important for nitty-gritty seismologists like myself, who do imaging of current mantle structure and estimate its water content, but it's also important for people hunting for water-bearing exoplanets and asking about the origins of where our water came from."

Dong and Fischer are now using the same approach to calculate how much water may be held inside Mars.

"Today, Mars looks very cold and dry," Dong said. "But a lot of geochemical and geomorphological evidence suggests that early Mars might have contained some water on the surface - and even a small ocean - so there's a lot of interest in understanding the water cycle on Mars."

INFORMATION:

AGU (http://www.agu.org) supports 130,000 enthusiasts to experts worldwide in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, we advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.??

Notes for Journalists

This research study will be freely available for 30 days. Download a PDF copy of the paper here. Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

Paper title:

"Constraining the volume of Earth's early oceans with a temperature?dependent mantle water storage capacity model"

Authors:

Junjie Dong, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Rebecca A. Fischer, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Lars P. Stixrude, University of California, Los Angeles, California

Carolina R. Lithgow?Bertelloni, University of California, Los Angeles, California

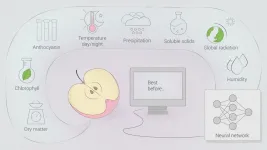

A researcher from Skoltech and his German colleagues have developed a neural network-based classification algorithm that can use data from an apple orchard to predict how well apples will fare in long-term storage. The paper was published in Computers and Electronics in Agriculture.

Before the fruit and vegetables we all like end up on our tables, they have to be stored for quite some time, and during this time they can develop physiological disorders such as flesh browning or superficial scald (brown or black patches on the skin of the fruit). These disorders contribute to the loss of a substantial amount ...

Some 8,300 million metric tons of plastics have been manufactured since production exploded in the 1950s, with more than 75 percent ending up as waste and 15 million metric tons reaching oceans every year. Plastic waste fragments into increasingly smaller but environmentally persistent "microplastics," with potentially harmful effects on the health of people, wildlife and ecosystems. A new collection, "Confronting Plastic Pollution to Protect Environmental and Public Health," is publishing on March 30th, 2021 in the open access journal PLOS Biology that addresses critical scientific challenges in understanding the impacts of microplastics.

The collection features three evidence-based commentaries from ecotoxicology and environmental health ...

RESTON, Va. - Greater sage-grouse populations have declined significantly over the last six decades, with an 80% rangewide decline since 1965 and a nearly 40% decline since 2002, according to a new report by the U.S. Geological Survey. Although the overall trend clearly shows continued population declines over the entire range of the species, rates of change do vary regionally.

The report represents the most comprehensive analysis of greater sage-grouse population trends ever produced and lays out a monitoring framework to assess those trends moving forward. The study can also be used to evaluate the effectiveness of greater sage-grouse conservation efforts and analyze factors that contribute to habitat loss and population change -- all critical ...

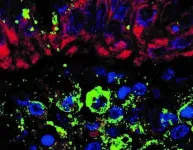

(Philadelphia, PA) - The human heart works under high demand, constantly pumping oxygen-rich blood through the body. When faced with disease, however, fulfilling this demand can become increasingly difficult and harmful. In the case of chronic high blood pressure - a leading cardiovascular disease in the United States - the heart continuously overexerts, resulting in maladaptive growth and, ultimately, severe dysfunction of the heart muscle itself.

Maladaptive growth of the heart, known as cardiac hypertrophy, is brought about in part by activation of G protein-coupled kinase ...

Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis reported the first observations of a new form of fluorine, the isotope 13F, described in the journal Physical Review Letters.

They made their discovery as part of an experiment conducted at the National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory at Michigan State University (MSU).

Fluorine is the most chemically reactive element on the periodic table. Only one isotope of fluorine occurs naturally, the stable isotope 19F. The new isotope, 13F, is four neutrons removed from the proton drip line, the boundary that delimits the zone beyond which atomic nuclei decay by the emission ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- More than just a sign of illness, mucus is a critical part of our body's defenses against disease. Every day, our bodies produce more than a liter of the slippery substance, covering a surface area of more than 400 square meters to trap and disarm microbial invaders.

Mucus is made from mucins -- proteins that are decorated with sugar molecules. Many scientists are trying to create synthetic versions of mucins in hopes of replicating their beneficial traits. In a new study, researchers from MIT have now generated synthetic mucins with a polymer backbone that more accurately mimic the structure and function of naturally occurring mucins. The team also showed that these synthetic mucins could effectively neutralize the bacterial toxin that causes cholera.

The ...

A study conducted at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, shows that compounds produced by gut microbiota (bacteria and other microorganisms) during fermentation of insoluble fiber from dietary plant matter do not affect the ability of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 to enter and replicate in cells lining the intestines. However, while in vitro treatment of cells with these molecules did not significantly influence local tissue infection, it reduced the expression of a gene that plays a key role in viral cell entry and a cytokine receptor that favors inflammation.

An ...

HERSHEY, Pa. -- Stress, increased free time and feelings of boredom may have contributed to an increase in the number of cigarettes smoked per day during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic by nearly a third of surveyed Pennsylvania smokers. Penn State College of Medicine researchers said understanding risk factors and developing new strategies for smoking cessation and harm reduction may help public health officials address concerning trends in tobacco use that may have developed as a result of the pandemic.

Jessica Yingst, assistant professor of public health sciences and Penn State Cancer Institute researcher, said smokers who increased the number of cigarettes they smoked per day could be at greater risk of dependence and have a more difficult ...

March 30, 2021 - As cancer survival rates improve, more people are living with the aftereffects of cancer treatment. For some patients, these issues include chronic radiation-induced skin injury - which can lead to potentially severe cosmetic and functional problems.

Recent studies suggest a promising new approach in these cases, using fat grafting procedures to unleash the healing and regenerative power of the body's natural adipose stem cells (ASCs). "Preliminary evidence suggests that fat grafting can make skin feel and look healthier, restore lost soft tissue volume, and help alleviate pain and fibrosis in patients with radiation-induced skin injury ...

Giant trees in tropical forests, witnesses to centuries of civilization, may be trapped in a dangerous feedback loop according to a new report in Nature Plants from researchers at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama and the University of Birmingham, U.K. The biggest trees store half of the carbon in mature tropical forests, but they could be at risk of death as a result of climate change--releasing massive amounts of carbon back into the atmosphere.

Evan Gora, STRI Tupper postdoctoral fellow, studies the role of lightning in tropical forests. Adriane Esquivel-Muelbert, lecturer at the University of Birmingham, studies the effects of climate change in the Amazon. The two teamed up ...