(Press-News.org) (Philadelphia, PA) - The human heart works under high demand, constantly pumping oxygen-rich blood through the body. When faced with disease, however, fulfilling this demand can become increasingly difficult and harmful. In the case of chronic high blood pressure - a leading cardiovascular disease in the United States - the heart continuously overexerts, resulting in maladaptive growth and, ultimately, severe dysfunction of the heart muscle itself.

Maladaptive growth of the heart, known as cardiac hypertrophy, is brought about in part by activation of G protein-coupled kinase 5 (GRK5), a signaling molecule found within heart cells that previously has been linked to worsened cardiac function in heart failure. Researchers at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University (LKSOM) now show for the first time in animals that keeping GRK5 out of the heart cell nucleus, the compartment that houses the cell's genes, can block this abnormal growth process.

The new findings, published online March 30 in the journal Science Signaling, open exciting avenues for the development of GRK5-based therapies to prevent heart failure, a disease in which the heart is no longer able to pump blood through the body. Heart failure typically develops after years of the heart compensating for the effects of high blood pressure.

"GRK5 acts as a pathological gene regulator in the heart, with its activity specifically in the heart cell nucleus being a major factor driving cardiac hypertrophy in heart failure," explained Walter J. Koch, PhD, W.W. Smith Endowed Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine, Professor and Chair of the Department of Pharmacology, Director of the Center for Translational Medicine at LKSOM, and senior investigator on the new study.

GRK5 normally hangs out in the cell membrane. But in the heart, in response to hypertrophic stress, it translocates to the nucleus, binds to certain factors that regulate genes, and thereby triggers the production of proteins involved in tissue growth.

To assess the possibility of preventing this GRK5-driven abnormal growth of heart tissue, Dr. Koch's team developed a novel peptide molecule that encodes a portion of the GRK5 molecule involved in nuclear translocation. The peptide, named GRK5nt, inhibited GRK5 entry into the nucleus, blocking its growth-signaling capabilities.

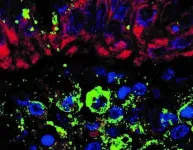

Dr. Ryan C. Coleman, a former graduate student in the Koch laboratory and first author on the report, carried out initial experiments with peptide in heart cells cultured in vitro. These experiments showed that the peptide's expression attenuates the activation of genes involved in maladaptive stress responses. In vitro studies further confirmed that GRK5nt works by binding to and occupying a portion of the GRK5 molecule known as the calmodulin (CaM) domain, which GRK5 otherwise depends on to gain entry into the nucleus.

The researchers next tested the effects of nuclear targeting in a mouse model in which animals were engineered to express GRK5nt in the heart. Some animals further underwent surgical aortic constriction, a procedure that mimics pressure overload in the human heart. Relative to animals with normal GRK5, those expressing GRK5nt exhibited reduced maladaptive effects, including reduced hypertrophy, in response to pressure overload.

"The reduction in pathological signaling provides new insights into the possibility of designing therapies to specifically target the pathological nuclear signaling of GRK5, while preserving normal GRK5 function in other tissues," Dr. Coleman said.

"The findings are very exciting, since they show that by keeping GRK5 out of the nucleus, we can stop abnormal growth and progression of heart failure," Dr. Koch added.

Now with proof-of-principle that nuclear targeting can eliminate the pathological effects of GRK5, Dr. Koch and colleagues plan next to test their strategy in an animal model of heart failure. In preparation for therapeutic testing, they also plan to explore mechanisms for targeted delivery of the peptide to the heart.

INFORMATION:

Other researchers who contributed to the study include Akito Eguchi, Melissa Lieu, Rajika Roy, Jessica Ibetti, Anna Maria Lucchese, Amanda M. Peluzzo, Kenneth Gresham, and J. Kurt Chuprun, Center for Translational Medicine, LKSOM; and Eric W. Barr, Department of Physiology, LKSOM.

The research was funded in part by National Institutes of Health grants P01 HL091799 and P01 HL075443.

About Temple Health

Temple University Health System (TUHS) is a $2.2 billion academic health system dedicated to providing access to quality patient care and supporting excellence in medical education and research. The Health System includes Temple University Hospital (TUH); TUH-Episcopal Campus; TUH-Jeanes Campus; TUH-Northeastern Campus; Temple University Hospital - Fox Chase Cancer Center Outpatient Department; TUH-Northeastern Endoscopy Center; The Hospital of Fox Chase Cancer Center, together with The Institute for Cancer Research, an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center; Fox Chase Cancer Center Medical Group, Inc., The Hospital of Fox Chase Cancer Center's physician practice plan; Temple Transport Team, a ground and air-ambulance company; Temple Physicians, Inc., a network of community-based specialty and primary-care physician practices; and Temple Faculty Practice Plan, Inc., TUHS's physician practice plan. TUHS is affiliated with the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

Temple Health refers to the health, education and research activities carried out by the affiliates of Temple University Health System (TUHS) and by the Katz School of Medicine. TUHS neither provides nor controls the provision of health care. All health care is provided by its member organizations or independent health care providers affiliated with TUHS member organizations. Each TUHS member organization is owned and operated pursuant to its governing documents.

Non-discrimination notice: It is the policy of Temple University Hospital and The Hospital of Fox Chase Cancer Center, that no one shall be excluded from or denied the benefits of or participation in the delivery of quality medical care on the basis of race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity/expression, disability, age, ancestry, color, national origin, physical ability, level of education, or source of payment.

Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis reported the first observations of a new form of fluorine, the isotope 13F, described in the journal Physical Review Letters.

They made their discovery as part of an experiment conducted at the National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory at Michigan State University (MSU).

Fluorine is the most chemically reactive element on the periodic table. Only one isotope of fluorine occurs naturally, the stable isotope 19F. The new isotope, 13F, is four neutrons removed from the proton drip line, the boundary that delimits the zone beyond which atomic nuclei decay by the emission ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- More than just a sign of illness, mucus is a critical part of our body's defenses against disease. Every day, our bodies produce more than a liter of the slippery substance, covering a surface area of more than 400 square meters to trap and disarm microbial invaders.

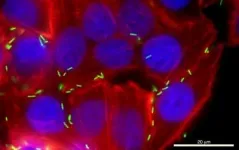

Mucus is made from mucins -- proteins that are decorated with sugar molecules. Many scientists are trying to create synthetic versions of mucins in hopes of replicating their beneficial traits. In a new study, researchers from MIT have now generated synthetic mucins with a polymer backbone that more accurately mimic the structure and function of naturally occurring mucins. The team also showed that these synthetic mucins could effectively neutralize the bacterial toxin that causes cholera.

The ...

A study conducted at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, shows that compounds produced by gut microbiota (bacteria and other microorganisms) during fermentation of insoluble fiber from dietary plant matter do not affect the ability of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 to enter and replicate in cells lining the intestines. However, while in vitro treatment of cells with these molecules did not significantly influence local tissue infection, it reduced the expression of a gene that plays a key role in viral cell entry and a cytokine receptor that favors inflammation.

An ...

HERSHEY, Pa. -- Stress, increased free time and feelings of boredom may have contributed to an increase in the number of cigarettes smoked per day during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic by nearly a third of surveyed Pennsylvania smokers. Penn State College of Medicine researchers said understanding risk factors and developing new strategies for smoking cessation and harm reduction may help public health officials address concerning trends in tobacco use that may have developed as a result of the pandemic.

Jessica Yingst, assistant professor of public health sciences and Penn State Cancer Institute researcher, said smokers who increased the number of cigarettes they smoked per day could be at greater risk of dependence and have a more difficult ...

March 30, 2021 - As cancer survival rates improve, more people are living with the aftereffects of cancer treatment. For some patients, these issues include chronic radiation-induced skin injury - which can lead to potentially severe cosmetic and functional problems.

Recent studies suggest a promising new approach in these cases, using fat grafting procedures to unleash the healing and regenerative power of the body's natural adipose stem cells (ASCs). "Preliminary evidence suggests that fat grafting can make skin feel and look healthier, restore lost soft tissue volume, and help alleviate pain and fibrosis in patients with radiation-induced skin injury ...

Giant trees in tropical forests, witnesses to centuries of civilization, may be trapped in a dangerous feedback loop according to a new report in Nature Plants from researchers at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama and the University of Birmingham, U.K. The biggest trees store half of the carbon in mature tropical forests, but they could be at risk of death as a result of climate change--releasing massive amounts of carbon back into the atmosphere.

Evan Gora, STRI Tupper postdoctoral fellow, studies the role of lightning in tropical forests. Adriane Esquivel-Muelbert, lecturer at the University of Birmingham, studies the effects of climate change in the Amazon. The two teamed up ...

PULLMAN, Wash. - Washington State University researchers have discovered a protein that could be key to blocking the most common bacterial cause of human food poisoning in the United States.

Chances are, if you've eaten undercooked poultry or cross contaminated food by washing raw chicken, you may be familiar with the food-borne pathogen.

"Many people that get sick think, 'oh, that's probably Salmonella,' but it is even more likely it's Campylobacter," said Nick Negretti ('20 Ph.D.), a lead member of the research team in Michael Konkel's Laboratory in WSU's School of Molecular Biosciences.

According to a study on the research recently published ...

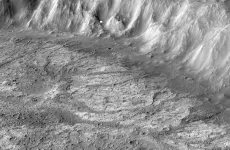

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- Researchers from Brown University have discovered a previously unknown type of ancient crater lake on Mars that could reveal clues about the planet's early climate.

In a study published in Planetary Science Journal, a research team led by Brown Ph.D. student Ben Boatwright describes an as-yet unnamed crater with some puzzling characteristics. The crater's floor has unmistakable geologic evidence of ancient stream beds and ponds, yet there's no evidence of inlet channels where water could have entered the crater from outside, and no evidence ...

Judges don't do court stenography. CEOs don't take minutes at meetings. So why do we expect doctors and other health care providers to spend hours recording notes -- something experts know contributes to burnout?

"Having them do so much clerical work doesn't make sense," said Lisa Merlo, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry and director of wellness programs at the University of Florida College of Medicine. "In order to improve the health care experience for everyone, we need to help them focus more on the actual practice of medicine."

Physician burnout affects patients, too. Stressed doctors are less compassionate and more likely to make mistakes. Clinicians who leave the field or cut back hours reduce patient access ...

Mount Sinai researchers have found that a widely available and inexpensive drug targeting inflammatory genes has reduced morbidity and mortality in mice infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. In a study published today in the journal Cell, the team reported that the drug, Topotecan (TPT), inhibited the expression of inflammatory genes in the lungs of mice as late as four days after infection, a finding with potential implications for treatment of humans.

"So far, in pre-clinical models of SARS-CoV-2, there are no therapies--either antiviral, antibody, or plasma--shown to reduce the SARS-CoV-2 disease burden when administered after more than one day post-infection" says senior author Ivan Marazzi, PhD, Associate Professor of Microbiology ...