(Press-News.org) Sugar practically screams from the shelves of your grocery store, especially those products marketed to kids.

Children are the highest consumers of added sugar, even as high-sugar diets have been linked to health effects like obesity and heart disease and even impaired memory function.

However, less is known about how high sugar consumption during childhood affects the development of the brain, specifically a region known to be critically important for learning and memory called the hippocampus.

New research led by a University of Georgia faculty member in collaboration with a University of Southern California research group has shown in a rodent model that daily consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages during adolescence impairs performance on a learning and memory task during adulthood. The group further showed that changes in the bacteria in the gut may be the key to the sugar-induced memory impairment.

Supporting this possibility, they found that similar memory deficits were observed even when the bacteria, called Parabacteroides, were experimentally enriched in the guts of animals that had never consumed sugar.

"Early life sugar increased Parabacteroides levels, and the higher the levels of Parabacteroides, the worse the animals did in the task," said Emily Noble, assistant professor in the UGA College of Family and Consumer Sciences who served as first author on the paper. "We found that the bacteria alone was sufficient to impair memory in the same way as sugar, but it also impaired other types of memory functions as well."

Guidelines recommend limiting sugar

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, a joint publication of the U.S. Departments of Agriculture and of Health and Human Services, recommends limiting added sugars to less than 10 percent of calories per day.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show Americans between the ages 9-18 exceed that recommendation, the bulk of the calories coming from sugar-sweetened beverages.

Considering the role the hippocampus plays in a variety of cognitive functions and the fact the area is still developing into late adolescence, researchers sought to understand more about its vulnerability to a high-sugar diet via gut microbiota.

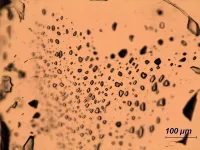

Juvenile rats were given their normal chow and an 11% sugar solution, which is comparable to commercially available sugar-sweetened beverages.

Researchers then had the rats perform a hippocampus-dependent memory task designed to measure episodic contextual memory, or remembering the context where they had seen a familiar object before.

"We found that rats that consumed sugar in early life had an impaired capacity to discriminate that an object was novel to a specific context, a task the rats that were not given sugar were able to do," Noble said.

A second memory task measured basic recognition memory, a hippocampal-independent memory function that involves the animals' ability to recognize something they had seen previously.

In this task, sugar had no effect on the animals' recognition memory.

"Early life sugar consumption seems to selectively impair their hippocampal learning and memory," Noble said.

Additional analyses determined that high sugar consumption led to elevated levels of Parabacteroides in the gut microbiome, the more than 100 trillion microorganisms in the gastrointestinal tract that play a role in human health and disease.

To better identify the mechanism by which the bacteria impacted memory and learning, researchers experimentally increased levels of Parabacteroides in the microbiome of rats that had never consumed sugar. Those animals showed impairments in both hippocampal dependent and hippocampal-independent memory tasks.

"(The bacteria) induced some cognitive deficits on its own," Noble said.

Noble said future research is needed to better identify specific pathways by which this gut-brain signaling operates.

"The question now is how do these populations of bacteria in the gut alter the development of the brain?" Noble said. "Identifying how the bacteria in the gut are impacting brain development will tell us about what sort of internal environment the brain needs in order to grow in a healthy way."

INFORMATION:

The article, "Gut microbial taxa elevated by dietary sugar disrupt memory function," appears in Translational Psychiatry. Scott Kanoski, associate professor in USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Science, is corresponding author on the paper.

Additional authors on the paper are Scott Kanoski, Elizabeth Davis, Linda Tsan, Clarissa Liu, Andrea Suarez and Roshonda B. Jones from the University of Southern California; Christine Olson, Yen-Wei Chen, Xia Yang and Elaine Y. Hsiao from the University of California-Los Angeles; and Claire de La Serre and Ruth Schade from UGA.

LAWRENCE, KANSAS -- The phrase "to see red" means to become angry. But for investors, seeing red takes on a whole different meaning.

William BazleyThat's the premise behind a new article by William Bazley, assistant professor of finance at the University of Kansas.

"Visual Finance: The Pervasive Effects of Red on Investor Behavior" reveals that using the color red to represent financial data influences individuals' risk preferences, expectations of future stock returns and trading decisions. The effects are not present in people who are colorblind, and they're muted in China, where red represents prosperity. Other colors do not generate the same outcomes.

The ...

As demand for low-carbon electricity rises around the world, nuclear power offers a promising solution. But how many countries are good candidates for nuclear energy development?

A new study in the journal Risk Analysis suggests that countries representing more than 80 percent of potential growth in low-carbon electricity demand--in Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa--may lack the economic or institutional quality to deploy nuclear power to meet their energy needs. The authors suggest that if nuclear power is to safely expand its role in mitigating climate change, countries need to radically improve their ability to manage the technology.

"Efforts to enhance institutional quality in these countries must be redoubled and could well be one of the ...

Taking progestogens - steroid hormones - during pregnancy could reduce the risk of preterm birth in high-risk single baby pregnancies, research has shown.

Although these compounds have been in use for some time, results of individual clinical trials investigating their effectiveness in preventing preterm birth have been conflicting, and so further evaluation of the research evidence was needed.

University of York researchers led the Evaluating Progestogens for Prevention of Preterm Birth International Collaborative (EPPPIC) project, a systematic review which brought together and re-analysed datasets from 31 clinical trials of progestogens, including more than 11,000 women and 16,000 babies ...

Microbial life already had the necessary conditions to exist on our planet 3.5 billion years ago. This was the conclusion reached by a research team after studying microscopic fluid inclusions in barium sulfate (barite) from the Dresser Mine in Marble Bar, Australia. In their publication "Ingredients for microbial life preserved in 3.5-billion-year-old fluid inclusions," the researchers suggest that organic carbon compounds which could serve as nutrients for microbial life already existed at this time. The study by first author Helge Mißbach (University of Göttingen, Germany) was published in the journal ...

Researchers from the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) of the Chinese Academy of Science (CAS), teamed up with scientists from Aix Marseille University, discovered that hematopoietic progenitors possessed the differentiation potential to type 1 innate lymphoid cells (ILC1s) in adult liver, and dissected the regulation mechanisms of such cell differentiation, revealing the pathways that lead to the development of tissue-resident lymphocytes. This study was published in Science.

Hematopoiesis occurs at different sites following the development of human body. After birth, the bone marrow (BM) has long been known to be the main hematopoietic organ ...

ST segment-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is a particularly severe type of heart attack associated with a high risk of mortality or long-term disability. Clinicians can reduce a patient's chances of unfavorable outcomes by performing a procedure known as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), which combines coronary angioplasty--in which a balloon is inserted into a blocked artery of the heart to clear it--with stenting--inserting a tiny tube into a blocked artery to keep the line open. But studies in China have found that many patients with STEMI choose not to undergo PCI and that women with STEMI, in particular, have a reduced likelihood of undergoing guideline-based ...

By harvesting energy from their surrounding environments, particles named 'artificial micromotors' can propel themselves in specific directions when placed in aqueous solutions. In current research, a popular choice of micromotor is the spherical 'Janus particle' - featuring two distinct sides with different physical properties. Until now, however, few studies have explored how these particles interact with other objects in their surrounding microenvironments. In an experiment detailed in EPJ E, researchers in Germany and The Netherlands, led by Larysa Baraban at Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf, show for the first time how the velocities of Janus particles relate to the physical properties of nearby barriers.

The team's discoveries could help researchers to engineer micromotors which ...

Children with a common but regularly undiagnosed disorder affecting their language and communication are likely to be finding the transition back to school post-lockdown harder than most, according to a team of psychologists.

Two children in every class of 30 are estimated to have Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) (around 8%), yet public awareness, diagnosis and referral to speech and language therapists all remain low in the UK.

DLD is a condition where children have problems acquiring their own language for no obvious reasons. Unlike temporary language delay (which reflects the natural variation of age at which children learn to speak and communicate), DLD is a lifelong condition with significant impacts for individuals in childhood and in later life, in particular their ...

Lakes store huge amounts of methane. In a new study, environmental scientists at the University of Basel offer suggestions for how it can be extracted and used as an energy source in the form of methanol.

Discussion about the current climate crisis usually focuses on carbon dioxide (CO2). The greenhouse gas methane is less well known, but although it is much rarer in the atmosphere, its global warming potential is 80 to 100 times greater per unit.

More than half the methane caused by human activities comes from oil production and agricultural fertilizers. But the gas is also created by the natural decomposition of biomass by ...

Scientists from Trinity College Dublin believe they have pinpointed our most distant animal relative in the tree of life and, in doing so, have resolved an ongoing debate. Their work finds strong evidence that sponges - not more complex comb jellies - were our most distant relatives.

Sponges are structurally simple, lacking complex traits such as a nervous system, muscles, and a though-gut. Logically, you would expect these complex traits to have emerged only once during animal evolution - after our lineage diverged from that of sponges - and then be retained in newly evolved creatures thereafter.

However, a debate has been raging ever since phylogenomic studies found evidence that our most distant ...