(Press-News.org) When we watch a mime seemingly pull rope, climb steps or try to escape that infernal box, we don't struggle to recognize the implied objects -- our minds automatically "see" them, a new study concludes.

To explore how the mind processes the objects mimes seem to interact with, Johns Hopkins University cognitive scientists brought the art of miming into the lab, concluding that invisible, implied surfaces are represented rapidly and automatically. The work appears today in the journal Psychological Science.

"Most of the time, we know which objects are around us because we can just see them directly. But what we explored here was how the mind automatically builds representations of objects that we can't see at all but that we know must be there because of how they are affecting the world," said senior author Chaz Firestone, an assistant professor who directs the university's Perception & Mind Laboratory. "That's basically what mimes do. They can make us feel like we're aware of some object just by seeming to interact with it."

In the experiments, 360 people were tested online. They watched clips where a character (Firestone himself) mimed colliding with a wall and stepping over a box in a way that suggested those objects were there, only invisible. Afterward, a black line appeared in the spot on the screen where the implied surface would have been. This line could be horizontal or vertical, so it either matched or didn't match the orientation of the surface that had just been mimed. Participants had to quickly answer if the line was vertical or horizontal. The team found people responded significantly faster when the line aligned with the mimed wall or box, suggesting that the implied surface was actively represented in the mind - so much so that it affected responses to the real surface participants saw immediately after.

Participants had been told not to pay attention to the miming, but they couldn't help but be influenced by those implied surfaces, said lead author Pat Little, who did the work as an undergraduate at Johns Hopkins, and is now a graduate student at New York University.

"Very quickly people realize that the mime is misleading them, and that there is no actual connection between what the person does and the type of line that appears," Little said. "They think, 'I should ignore this thing because it's getting in my way', but they can't. That's the key. It seems like our minds can't help but represent the surface that the mime is interacting with - even when we don't want to."

The work is partly inspired by a phenomenon in psychology called the Stroop Effect, where the name for one color is written in ink of a different color (e.g., the word "red" is written in blue ink); when a person is given the task of saying the color of the ink (blue), they can't help but read the mismatched text (red), which distracts them and slows them down. In this regard, miming is like reading: Just as you can't help but read the text you see (even when you're supposed to ignore it), you can't help but recognize the object being mimed, even when it's getting in the way of another task.

While it could seem that the findings diminish the work of mimes - since it suggests our brains are going to imagine these objects automatically - the researchers insist mimes still deserve credit.

"This suggests that miming might be different from other kinds of acting," Little said. "If the mime is skilled enough, understanding what's going on doesn't require any effort at all -- you just get it automatically."

The findings could also inform artificial intelligence related to vision.

"If you're trying to build a self-driving car that can see the world and steer around objects, you want to give it all the best tools and tricks," Firestone said. "This study suggests that, if you want a machine's vision to be as sophisticated as ours, it's not enough for it to identify objects that it can see directly -- it also needs the ability to infer the existence of objects that aren't even visible at all."

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant #2021053), the Johns Hopkins Science of Learning Institute, and a STAR award from the Johns Hopkins Office of Undergraduate Research.

In the 1960s, a national focus on hunger was essential to address major problems of undernutrition after World War II. In the 1990s, the nation shifted away from hunger toward "food insecurity" to better capture and address the challenges of food access and affordability.

Now, a END ...

Space scientists at the University of Bath in the UK have found a new way to probe the internal structure of neutron stars, giving nuclear physicists a novel tool for studying the structures that make up matter at an atomic level.

Neutron stars are dead stars that have been compressed by gravity to the size of small cities. They contain the most extreme matter in the universe, meaning they are the densest objects in existence (for comparison, if Earth were compressed to the density of a neutron star, it would measure just a few hundred meters in diameter, and all humans would fit in a teaspoon). This makes neutron stars unique natural laboratories ...

Recent research from the University of Vaasa and the University of Jyväskyla shows that speculation and lottery-like behavior is a fundamental factor for the pricing of cryptocurrencies. Speculation could explain the enormous increase in the market capitalizations of cryptocurrencies.

Nowadays more than 8000 cryptocurrencies have been launched. Unlike traditional assets like stocks, research has shown that investments in cryptocurrencies are associated with a considerably higher level of uncertainty. The price of Bitcoin, which is the first traded cryptocurrency, increased by from $7,200.17 to $29,374.15 in January 1, 2020 ...

A team of researchers at the University of Alberta has uncovered a long-sought link in the battle to control cholesterol and heart disease.

The protein that interferes with low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors that clear "bad" cholesterol from the blood was identified in END ...

MADISON - Bipolar disorder affects millions of Americans, causing dramatic swings in mood and, in some people, additional effects such as memory problems.

While bipolar disorder is linked to many genes, each one making small contributions to the disease, scientists don't know just how those genes ultimately give rise to the disorder's effects.

However, in new research, scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have found for the first time that disruptions to a particular protein called Akt can lead to the brain changes characteristic of bipolar disorder. The results offer a foundation for research into treating the often-overlooked cognitive impairments of bipolar disorder, ...

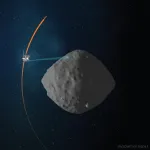

NASA's OSIRIS-REx mission is on the brink of discovering the extent of the mess it made on asteroid Bennu's surface during last fall's sample collection event. On Apr. 7, the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft will get one last close encounter with Bennu as it performs a final flyover to capture images of the asteroid's surface. While performing the flyover, the spacecraft will observe Bennu from a distance of about 2.3 miles (3.7 km) - the closest it's been since the Touch-and-Go Sample Collection event on Oct. 20, 2020.

The OSIRIS-REx team decided to add this last flyover after Bennu's surface was significantly disturbed by the sample collection event. During touchdown, the spacecraft's ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University and Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center] -- Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) are an emerging assistive technology, enabling people with paralysis to type on computer screens or manipulate robotic prostheses just by thinking about moving their own bodies. For years, investigational BCIs used in clinical trials have required cables to connect the sensing array in the brain to computers that decode the signals and use them to drive external devices.

Now, for the first time, BrainGate clinical trial participants with tetraplegia have demonstrated use of an intracortical wireless BCI with an external wireless transmitter. The system is capable of transmitting brain signals at single-neuron resolution and ...

Few compounds are as important to industry and medicine today as titanium dioxide. Despite the variety and popularity of its applications, many issues related to the surface structure of materials made of this compound and the processes taking place therein remain unclear. Some of these secrets have just been revealed to scientists from the Institute of Nuclear Physics of the Polish Academy of Sciences. It was the first time they had used the SOLARIS synchrotron in their research.

It is found in many chemical reactions as a catalyst, as a pigment in plastics, paints or cosmetics and in medical implants it ...

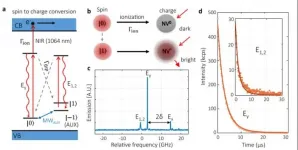

The team led by Professor DU Jiangfeng and Professor WANG Ya from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) Key Laboratory of Microscale Magnetic Resonance of the University of Science and Technology of China put forward an innovative spin-to-charge conversion method to achieve high-fidelity readout of qubits, stepping closer towards fault-tolerant quantum computing.

Quantum supremacy over classical computers has been fully exhibited in some specific problems, yet the next milestone, fault-tolerant quantum computing, still requires the accumulated logic gate error and the spin readout fidelity to exceed the fault-tolerant threshold. DU's team has resolved the first requirement in the nitrogen-vacancy (NV) center system ...

Pollen from trees, grasses and weeds are causing seasonal allergies for approximately one fifth of the Swiss population every year. A study now found that due to climate change, the pollen season has shifted substantially over the past 30 years in onset, duration and intensity. "For at least four allergenic species, the tree pollen season now starts earlier than 30 years ago - sometimes even before January," said Marloes Eeftens, Principal Investigator and Group Leader at Swiss TPH. "The duration and intensity of the pollen season have also increased for several species, meaning that allergic people not only suffer for a longer period of time but also react stronger to these higher concentrations."

The researchers analysed pollen data from 1990 ...