(Press-News.org) Stem cell research has allowed medicine to go places that were once science fiction. Using stem cells, scientists have manufactured heart cells, brain cells and other cell types that they are now transplanting into patients as a form of cell therapy. Eventually, the field anticipates the same will be possible with organs. A new paper written by a group of international researchers led by Tsutomu Sawai, an assistant professor at the Kyoto University Institute for the Advanced Study of Human Biology (ASHBi) and the Center for iPS Cell Research and Application (CiRA), explains the future ethical implications of this research with regards to brain organoids, a laboratory-made structure that is designed to grow and behave like the brain.

In just over ten years, a new word has entered the lexicon of stem cell science. "Organoids" describe organ-like structures that imitate how organs form in the body. By recapitulating normal development, organoids have proven to be invaluable tools for understanding not only how organs grow, but also how diseases develop. Organoids have been reported for an assortment of organs, including the liver, kidney and, most controversially, the brain, along with others.

The brain is considered the source of our consciousness. Therefore, if brain organoids do truly mimic the brain, they too should develop consciousness, which, as the paper states, brings all sorts of moral implications.

"Consciousness is a very difficult property to define. We do not have very good experimental techniques that confirm consciousness. But even if we cannot prove consciousness, we should set guidelines, because scientific advancements demand it," said Sawai, who has spent several years writing about the ethics of brain organoid research.

Brain organoids have led to deep questions about consciousness. With some people imagining a future where our brains are uploaded and kept on the cloud well after our bodies die, organoids bring an opportunity to test consciousness and morality in artificial environments.

Ethicists have broken consciousness down into many types. Phenomenal consciousness assumes the awareness of pain, pleasure and distress. Sawai and his colleagues argue that even though restraints on experiments using brain organoids would be needed, phenomenal consciousness would not outright prohibit experiments, since animals commonly used in science, such as rodents and monkeys, also display phenomenal consciousness. Self-consciousness would add to the ethical conflicts, since this status bestows a higher morality.

However, Sawai said there is a more pressing issue.

"One of the biggest problems is transplants. Should we put brain organoids into animals to observe how the brain behaves?"

Stem cell research has presented the possibility of growing xeno-organs. For example, researchers have had profound success at growing mouse pancreas in rat and vice versa, and similar research is expected to lead to human pancreas being grown in pigs. In principle, these animals would become organ farms that can be harvested and circumvent the long wait time for organ donors.

While growing whole human brains inside animals is not under any serious consideration, transplanting brain organoids could give crucial insight on how diseases like dementia or schizophrenia form and treatments to cure them.

"This is still too futuristic, but that does not mean we should wait to decide on ethical guidelines. The concern is not so much a biological humanization of the animal, which can happen with any organoid, but a moral humanization, which is exclusive to the brain," said Sawai.

Other concerns, he added, include enhanced abilities - think Planet of the Apes. Furthermore, if the animal developed humanized traits, then treating it sub-humanely would violate human dignity, a core tenet of ethical practice.

The paper notes that some people do not consider these outcomes unethical. Enhanced abilities without a change in self-consciousness is equivalent to using a higher animal in experiments, like shifting from mouse to monkey. And a change in dignity does not mean a change to human dignity. Instead, the change could result in a new type of dignity.

Regardless, the authors believe that the possibility of unintended connections between the transplanted brain organoid to the animal brain deserves precautionary consideration.

The biggest concern regarding brain organoid transplantation, however, does not involve animals. There is good reason to believe that as research proceeds, the future will bring the possibility of transplanting these structures into patients who suffered from sudden trauma, stroke or other injury to the brain.

There are already a number of clinical trials that involve the transplantation of brain cells as a cell therapy in patients with such injury or neurodegenerative diseases. Sawai said that the ethics behind these therapies could act as a paradigm for brain organoids.

"Cell transplantations change the way brain cells function. If something goes wrong, we can't just take them out and start over. But right now, cell transplantation is usually in just one location. Brain organoids would be expected to interact more deeply with the brain, risking more unexpected changes," he believes.

In the end of 2018, the stem cell field was in uproar when a scientist announced that he had genetically engineered a human embryo that went to term. The actions of the scientist were in clear violation of international frameworks and resulted in his prison sentence.

To avoid a similar controversy and possible loss of public confidence in brain organoid research, the paper states explicitly that all stakeholders, including ethicists, policy-makers and scientists need to remain in constant communication about progress in this field.

"We need to regularly communicate with each other on scientific facts and their ethical, legal and social implications," said Sawai.

INFORMATION:

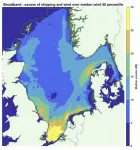

Travel and economic slowdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic combined to put the brakes on shipping, seafloor exploration, and many other human activities in the ocean, creating a unique moment to begin a time-series study of the impacts of sound on marine life.

A community of scientists has identified more than 200 non-military ocean hydrophones worldwide and hopes to make the most of the unprecedented opportunity to pool their recorded data into the 2020 quiet ocean assessment and to help monitor the ocean soundscape long into the future. They aim for a total of 500 hydrophones capturing the signals of whales and other marine life while assessing the racket levels of human activity. ...

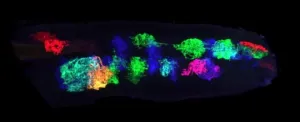

Animals are remarkably diverse in their sleep and activity patterns due to foraging strategies, social behavior and their desire to avoid predators. With more than 3,000 types of cichlids, these freshwater fish may just be one of the most diverse species in the world. Lake Malawi alone, which stretches 350 miles through eastern Africa, is home to more than 500 cichlid species. They evolved from a few species that likely entered the lake about 3 million years ago and now display very different behaviors and inhabit well-defined niches throughout ...

Scientists are reporting results of the first frontline clinical trial to use targeted therapy to treat high-risk pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma. The study showed that the addition of brentuximab vedotin achieved excellent outcomes, reduced side effects, and allowed for reduced radiation exposures.

The study was the result of work by a multi-site consortium dedicated to pediatric Hodgkin-lymphoma. Collaborating institutions include St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Stanford University School of Medicine, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, Maine Children's Cancer Program and OSF Children's Hospital of Illinois.

A paper detailing the findings was published today in ...

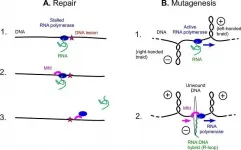

The Mfd protein repairs bacterial DNA, but can also, to scientists' surprise, promote mutation.

Bacterial mutations can lead to antibiotic resistance.

Understanding this second "role" of the Mfd protein opens up opportunities for combating antibiotic resistance, and also the resistance of tumours to anti-cancer drugs and therapies.

Using a specialized protein, all bacteria are capable of rapidly and effectively repairing damage to their DNA from UV. However, this mutation frequency decline (Mfd) protein plays another role and causes mutations. A team involving ...

In cancer, personalised medicine takes advantage of the unique genetic changes in an individual tumour to find its vulnerabilities and fight it. Many tumours have a higher number of mutations due to a antiviral defence mechanism, the APOBEC system, which can accidentally damage DNA and cause mutations.

Researchers at IRB Barcelona led by Dr. Travis Stracker and Dr. Fran Supek have found the HMCES enzyme to be the Achilles heel of some lung tumours, specifically those with a higher number of mutations caused by the APOBEC system.

"We have discovered that blocking HMCES is very damaging to cells with an activated ...

Hispanic immigrants of working age -- 20 to 54 years old -- are over 11 times more likely to die of COVID-19 than U.S.-born men and women who are not Hispanic, according to a USC study of California death certificate data from 2020.

The study, published Monday in the END ...

QUT researchers have used carbon dots, created from human hair waste sourced from a Brisbane barbershop, to create a kind of "armour" to improve the performance of cutting-edge solar technology.

In a study published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry A, the researchers led by Professor Hongxia Wang in collaboration with Associate Professor Prashant Sonar of QUT's Centre for Materials Science showed the carbon nanodots could be used to improve the performance of perovskites solar cells.

Perovskites solar cells, a relatively new photovoltaic technology, are seen as the best PV candidate to deliver low-cost, highly efficient solar electricity in coming years. ...

EUGENE, Ore. -- April 8, 2021 -- Researchers exploring the developing central nervous system of fruit flies have identified nonelectrical cells that transition the brain from highly plastic into a less moldable, mature state.

The cells, known as astrocytes for their star-like shapes, and associated genes eventually could become therapeutic targets, said University of Oregon postdoctoral researcher Sarah Ackerman, who led the research.

"All of the cell types and signaling pathways I looked at are present in humans," Ackerman said. "Two of the genes that I ...

More than a third of the Antarctic's ice shelf area could be at risk of collapsing into the sea if global temperatures reach 4°C above pre-industrial levels, new research has shown.

The University of Reading led the most detailed ever study forecasting how vulnerable the vast floating platforms of ice surrounding Antarctica will become to dramatic collapse events caused by melting and runoff, as climate change forces temperatures to rise.

It found that 34% of the area of all Antarctic ice shelves - around half a million square kilometres - including 67% of ice shelf area on the Antarctic Peninsula, would be at risk of destabilisation under 4°C of warming. Limiting temperature ...

INDIANAPOLIS--Worldwide, 1 in 4 people will suffer from a depressive episode in their lifetime.

While current diagnosis and treatment approaches are largely trial and error, a breakthrough study by Indiana University School of Medicine researchers sheds new light on the biological basis of mood disorders, and offers a promising blood test aimed at a precision medicine approach to treatment.

Led by Alexander B. Niculescu, MD, PhD, Professor of Psychiatry at IU School of Medicine, the study was published today in the high impact journal Molecular Psychiatry . The work builds on previous research conducted by Niculescu and his colleagues into blood biomarkers that track suicidality as well as pain, post-traumatic stress ...