(Press-News.org) Whatever ultimately caused inhabitants to abandon Cahokia, it was not because they cut down too many trees, according to new research from Washington University in St. Louis.

Archaeologists from Arts & Sciences excavated around earthen mounds and analyzed sediment cores to test a persistent theory about the collapse of Cahokia, the pre-Columbian Native American city in southwestern Illinois that was once home to more than 15,000 people.

No one knows for sure why people left Cahokia, though many environmental and social explanations have been proposed. One oft-repeated theory is tied to resource exploitation: specifically, that Native Americans from densely populated Cahokia deforested the area, an environmental misstep that could have resulted in erosion and localized flooding.

But such musings about self-inflicted disaster are outdated -- and they're not supported by physical evidence of flooding issues, Washington University scientists said.

"There's a really common narrative about land use practices that lead to erosion and sedimentation and contribute to all of these environmental consequences," said Caitlin Rankin, an assistant research scientist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign who conducted this work as part of her graduate studies at Washington University.

"When we actually revisit this, we're not seeing evidence of the flooding," Rankin said.

"The notion of looming ecocide is embedded in a lot of thinking about current and future environmental trajectories," said Tristram R. "T.R." Kidder, the Edward S. and Tedi Macias Professor of Anthropology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University. "With a growing population and more mouths to feed, overconsumption of all resources is a real risk.

"Inevitably, people turn to the past for models of what has happened. If we are to understand what caused changes at sites like Cahokia, and if we are to use these as models for understanding current possibilities, we need to do the hard slogging that critically evaluates different ideas," added Kidder, who leads an ongoing archaeological research program at the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site. "Such work allows us to sift through possibilities so we can aim for those variables that do help us to explain what happened in the past -- and explore if this has a lesson to tell us about the future."

No indications of self-inflicted harm

Writing in the journal Geoarchaeology, Rankin and colleagues at Bryn Mawr University and Northern Illinois University described their recent excavations around a Mississippian Period (AD 1050-1400) earthen mound in the Cahokia Creek floodplain.

Their new archaeological work, completed while Rankin was at Washington University, shows that the ground surface on which the mound was constructed remained stable until industrial development.

The presence of a stable ground surface from Mississippian occupation to the mid-1800s does not support the expectations of the so-called "wood-overuse" hypothesis, the researchers said.

This hypothesis, first proposed in 1993, suggests that tree clearance in the uplands surrounding Cahokia led to erosion, causing increasingly frequent and unpredictable floods of the local creek drainages in the floodplain where Cahokia was constructed.

Rankin noted that archaeologists have broadly applied narratives of ecocide -- the idea that societies fail because people overuse or irrevocably damage the natural resources that their people rely on -- to help to explain the collapse of past civilizations around the world.

Although many researchers have moved beyond classic narratives of ecocide made popular in the 1990s and early 2000s, Cahokia is one such major archaeological site where untested hypotheses have persisted.

"We need to be careful about the assumptions that we build into these narratives," Rankin said.

"In this case, there was evidence of heavy wood use," she said. "But that doesn't factor in the fact that people can reuse materials -- much as you might recycle. We should not automatically assume that deforestation was happening, or that deforestation caused this event."

Kidder said: "This research demonstrates conclusively that the over-exploitation hypothesis simply isn't tenable. This conclusion is important because the hypothesis at Cahokia -- and elsewhere -- is sensible on its face. The people who constructed this remarkable site had an effect on their environment. We know they cut down tens of thousands of trees to make the palisades -- and this isn't a wild estimate, because we can count the number of trees used to build and re-build this feature. Wood depletion could have been an issue."

"The hypothesis came to be accepted as truth without any testing," Kidder said. "Caitlin's study is important because she did the hard work -- and I do mean hard, and I do mean work -- to test the hypothesis, and in doing so has falsified the claim. I'd argue that this is the exciting part; it's basic and fundamental science. By eliminating this possibility, it moves us toward other explanations and requires we pursue other avenues of research."

INFORMATION:

Scientists could be a step closer to finding a way to reduce the impact of traumatic memories, according to a Texas A&M University study published recently in the journal END ...

New Haven, Conn. -- Alzheimer's disease is known for its slow attack on neurons crucial to memory and cognition. But why are these particular neurons in aging brains so susceptible to the disease's ravages, while others remain resilient?

A new study led by researchers at the Yale School of Medicine has found that susceptible neurons in the prefrontal cortex develop a "leak" in calcium storage with advancing age, they report April 8 in the journal Alzheimer's & Dementia, The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association. This disruption of calcium storage in turns ...

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - New insights into the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infections could bring better treatments for COVID-19 cases.

An international team of researchers unexpectedly found that a biochemical pathway, known as the immune complement system, is triggered in lung cells by the virus, which might explain why the disease is so difficult to treat. The research is published this week in the journal Science Immunology.

The researchers propose that the pairing of antiviral drugs with drugs that inhibit this process may be more effective. Using an in vitro model using human lung ...

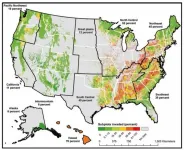

MADISON, WI, April 8, 2021 - USDA Forest Service scientists have delivered a new comprehensive assessment of the invasive species that confront America's forests and grasslands, from new arrivals to some that invaded so long ago that people are surprised to learn they are invasive.

The assessment, titled "Invasive Species in Forests and Rangelands of the United States: A Comprehensive Science Synthesis for the United States Forest Sector," serves as a one-stop resource for land managers who are looking for information on the invasive species that are already affecting the landscape, the species that may threaten the landscape, and what is known about control ...

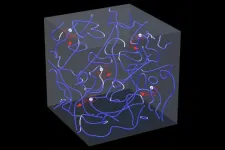

Nobel laureate in physics Richard Feynman once described turbulence as "the most important unsolved problem of classical physics."

Understanding turbulence in classical fluids like water and air is difficult partly because of the challenge in identifying the vortices swirling within those fluids. Locating vortex tubes and tracking their motion could greatly simplify the modeling of turbulence.

But that challenge is easier in quantum fluids, which exist at low enough temperatures that quantum mechanics -- which deals with physics on the scale of atoms or subatomic particles -- govern their behavior.

In a new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Florida State University researchers ...

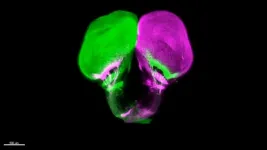

The network of nerves connecting our eyes to our brains is sophisticated and researchers have now shown that it evolved much earlier than previously thought, thanks to an unexpected source: the gar fish.

Michigan State University's Ingo Braasch has helped an international research team show that this connection scheme was already present in ancient fish at least 450 million years ago. That makes it about 100 million years older than previously believed.

"It's the first time for me that one of our publications literally changes the textbook that I am teaching with," said Braasch, as assistant professor in the Department of Integrative Biology in the College ...

URBANA, Ill. - When scientists need to understand the effects of new infant formula ingredients on brain development, it's rarely possible for them to carry out initial safety studies with human subjects. After all, few parents are willing to hand over their newborns to test unproven ingredients.

Enter the domestic pig. Its brain and gut development are strikingly similar to human infants - much more so than traditional lab animals, rats and mice. And, like infants, young pigs can be scanned using clinically available equipment, including non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI. That means researchers can test nutritional interventions in pigs, look at their effects on the developing brain via MRI, and make educated predictions about how those ...

Modern human-like brains evolved comparatively late in the genus Homo and long after the earliest humans first dispersed from Africa, according to a new study. By analyzing the impressions left behind by the ancient brains that once sat inside now fossilized skulls, the authors discovered that the brains of the earliest Homo retained a primitive, great ape-like organization of the frontal lobe. The findings challenge the long-standing assumption that human-like brain organization is a hallmark of early Homo and suggest that the evolutionary history of the human brain is more complex than previously thought. Our modern brains are larger and structurally different than those of our closest living relatives, ...

Researchers present a new, low-temperature method for injection-molding transparent fused silica glass, similar to how many plastic objects are manufactured. According to the authors, the process offers the possibility of producing complex and high-quality glass components using the same fabrication methods that allowed polymers to become one of the most important materials of the 21st century. The optical, thermal, mechanical and chemical properties of silicate glasses make them an ideal non-carbon based, high-performance material with applications ranging from packaging and architecture to high-throughput fiber optic ...

Using a novel genetic editing system termed intMEMOIR, researchers reveal the cell lineage histories of individual cells within their native tissue context, according to a new study. The new approach provides a powerful new tool for recording cell lineage in diverse cellular systems. During multicellular development, a cell's spatial position and lineage play important roles in cell fate determination. The ability to visualize lineage relationships directly within their native tissues can provide valuable insight into the factors that affect development and disease. This promise has spurred the development of several ...