(Press-News.org) A tiny protein of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that gives rise to COVID-19, may have big implications for future treatments, according to a team of Penn State researchers.

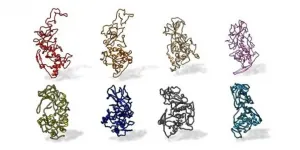

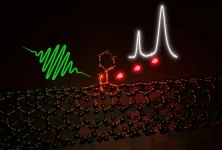

Using a novel toolkit of approaches, the scientists uncovered the first full structure of the Nucleocapsid (N) protein and discovered how antibodies from COVID-19 patients interact with that protein. They also determined that the structure appears similar across many coronaviruses, including recent COVID-19 variants -- making it an ideal target for advanced treatments and vaccines. They reported their results in Nanoscale.

"We discovered new features about the N protein structure that could have large implications in antibody testing and the long-term effects of all SARS-related pandemic viruses," said Deb Kelly, professor of biomedical engineering (BME), Huck Chair in Molecular Biophysics and director of the Penn State Center for Structural Oncology, who led the research. "Since it appears that the N protein is conserved across the variants of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-1, therapeutics designed to target the N protein could potentially help knock out the harsher or lasting symptoms some people experience."

Most of the diagnostic tests and available vaccines for COVID-19 were designed based on a larger SARS-CoV-2 protein -- the Spike protein -- where the virus attaches to healthy cells to begin the invasion process.

The Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines were designed to help recipients produce antibodies that protect against the Spike protein. However, Kelly said, the Spike protein can easily mutate, resulting in the variants that have emerged in the United Kingdom, South Africa, Brazil and across the United States.

Unlike the outer Spike protein, the N protein is encased in the virus, protected from environmental pressures that cause the Spike protein to change. In the blood, however, the N protein floats freely after it is released from infected cells. The free-roaming protein causes a strong immune response, leading to the production of protective antibodies. Most antibody-testing kits look for the N protein to determine if a person was previously infected with the virus -- as opposed to diagnostic tests that look for the Spike protein to determine if a person is currently infected.

"Everyone is looking at the Spike protein, and there are fewer studies being performed on the N protein," said Michael Casasanta, first author on the paper and a postdoctoral fellow in the Kelly laboratory. "There was this gap. We saw an opportunity -- we had the ideas and the resources to see what the N protein looks like."

Initially, the researchers examined the N protein sequences from humans, as well as different animals thought to be potential sources of the pandemic, such as bats, civets and pangolins. They all looked similar but distinctly different, according to Casasanta.

"The sequences can predict the structure of each of these N proteins, but you can't get all the information from a prediction -- you need to see the actual 3D structure," Casasanta said. "We converged the technology to see a new thing in a new way."

The researchers used an electron microscope to image both the N protein and the site on the N protein where antibodies bind, using serum from COVID-19 patients, and developed a 3D computer model of the structure. They found that the antibody binding site remained the same across every sample, making it a potential target to treat people with any of the known COVID-19 variants.

"If a therapeutic can be designed to target the N protein binding site, it might help reduce the inflammation and other lasting immune responses to COVID-19, especially in COVID long haulers," Kelly said, referring to people who experience COVID-19 symptoms for six weeks or longer.

The team procured purified N proteins, meaning the samples only contained N proteins, from RayBiotech Life and applied them to microchips developed in partnership with Protochips Inc. The microchips are made of silicon nitride, as opposed to a more traditional porous carbon, and they contain thin wells with special coatings that attract the N proteins to their surface. Once prepared, the samples were flash frozen and examined through cryo-electron microscopy.

Kelly credited her team's unique combination of microchips, thinner ice samples and Penn State's advanced electron microscopes outfitted with state-of-the-art detectors, customized from the company Direct Electron, for delivering the highest-resolution visualization of low-weight molecules from SARS-CoV-2 so far.

"The technology combined resulted in a unique finding," Kelly said. "Before, it was like trying to look at something frozen in the middle of the lake. Now, we're looking at it through an ice cube. We can see smaller entities with many more details and higher accuracy."

INFORMATION:

Casasanta and Kelly are both also affiliated with Penn State's Materials Research Institute (MRI). Co-authors include G.M. Jonaid, BME and Bioinformatics and Genomics Graduate Program in Penn State's Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences; Liam Kaylor and Maria J. Solares, BME and Molecular, Cellular, and Integrative Biosciences Graduate Program in the Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences; William Y. Luqiu, MRI and Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Duke University; Mariah Schroen, MRI; William J. Dearnaley, BME and MRI; Jared Wilson, RayBiotech Life; and Madeline J. Dukes, Protochips Inc.

The National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health and the Center for Structural Oncology in the Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences at Penn State funded this work.

Since 2016, a federal regulation has allowed nurse practitioners and physician assistants to obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine, a medication used to treat opioid use disorder as a medication assisted treatment.

But a recent study by Indiana University researchers found the bill, called the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA), has not greatly increased the amount of nurse practitioners prescribing buprenorphine, especially in states that have further restrictions. The study was published in Medical Care Research and Review.

"Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are an important workforce with a capacity to expand treatment access for those with substance use disorders," said Kosali Simon, ...

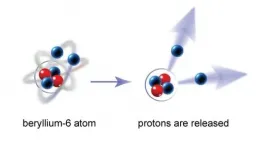

Michigan State University's Witold Nazarewicz has a simple way to describe the complex work he does at the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (frib.msu.edu), or FRIB.

"I study theoretical nuclear physics," said Nazarewicz, John A. Hannah Distinguished Professor of Physics and chief scientist at FRIB. "Nuclear theorists want to know what makes the nucleus tick."

There is a nucleus in every atom. Atoms, in turn, make up matter -- the stuff we interact with every day. But the nucleus is still shrouded in mystery. One of FRIB's goals in creating rare isotopes, or different forms of elements, is to better understand what's going on inside the cores of atoms.

In a new paper for END ...

Led by a South African team at the South African Medical Research Council Centre for Health Economics and Decision Science (PRICELESS-SA) in the School of Public Health at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (Wits), and the University of the Western Cape, in partnership with the University of North Carolina, USA, the study was published on 8 April in The Lancet Planetary Health.

South Africa faces an increasing burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease and cancers - diseases that can be linked to increased consumption of sugar, particularly ...

A clean energy future propelled by hydrogen fuel depends on figuring out how to reliably and efficiently split water. That's because, even though hydrogen is abundant, it must be derived from another substance that contains it -- and today, that substance is often methane gas. Scientists are seeking ways to isolate this energy-carrying element without using fossil fuels. That would pave the way for hydrogen-fueled cars, for example, that emit only water and warm air at the tailpipe.

Water, or H2O, unites hydrogen and oxygen. Hydrogen atoms in the form of molecular hydrogen must be separated out from this compound. That process depends on a key -- but often slow -- step: the oxygen evolution reaction (OER). The OER is what frees up molecular ...

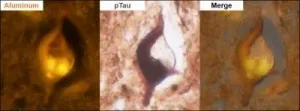

Amsterdam, April 9, 2021 -- This study builds upon two earlier published studies (Mold et al., 2020, Journal of Alzheimer's Disease Reports) from the same group. The new data, also published in the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease Reports, demonstrate that aluminum is co-located with phosphorylated tau protein, present as tangles within neurons in the brains of early-onset or familial Alzheimer's disease (AD). "The presence of these tangles is associated with neuronal cell death, and observations of aluminum in these tangles may highlight a role for aluminum in their formation," explained lead investigator Matthew John Mold, PhD, Birchall Centre, Lennard-Jones ...

The properties of carbon-based nanomaterials can be altered and engineered through the deliberate introduction of certain structural "imperfections" or defects. The challenge, however, is to control the number and type of these defects. In the case of carbon nanotubes - microscopically small tubular compounds that emit light in the near-infrared - chemists and materials scientists at Heidelberg University led by Prof. Dr Jana Zaumseil have now demonstrated a new reaction pathway to enable such defect control. It results in specific optically active defects - so-called sp3 defects - which are more luminescent and can emit single photons, that is, particles of light. The efficient ...

A new study using human genetics suggests researchers should prioritize clinical trials of drugs that target two proteins to manage COVID-19 in its early stages.

The findings appeared online in the journal Nature Medicine in March 2021.

Based on their analyses, the researchers are calling for prioritizing clinical trials of drugs targeting the proteins IFNAR2 and ACE2. The goal is to identify existing drugs, either FDA-approved or in clinical development for other conditions, that can be repurposed for the early management of COVID-19. Doing so, they say, will help keep people with the virus from being hospitalized.

IFNAR2 is the target ...

PHILADELPHIA - Psychosocial stress - typically resulting from difficulty coping with challenging environments - may work synergistically to put women at significantly higher risk of developing coronary heart disease, according to a study by researchers at Drexel University's Dornsife School of Public Health, recently published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

The study specifically suggests that the effects of job strain and social strain -- the negative aspect of social relationships -- on women is a powerful one-two punch. Together they are associated with a 21% higher risk of developing coronary heart disease. Job strain ...

There are millions of people who face the loss of their eyesight from degenerative eye diseases. The genetic disorder retinitis pigmentosa alone affects 1 in 4,000 people worldwide.

Today, there is technology available to offer partial eyesight to people with that syndrome. The Argus II, the world's first retinal prosthesis, reproduces some functions of a part of the eye essential to vision, to allow users to perceive movement and shapes.

While the field of retinal prostheses is still in its infancy, for hundreds of users around the globe, the "bionic eye" enriches the way they interact with the world on a daily basis. For instance, seeing outlines of objects enables them to move around unfamiliar environments with increased safety.

That is ...

A new biosealant therapy may help to stabilize injuries that cause cartilage to break down, paving the way for a future fix or - even better - begin working right away with new cells to enhance healing, according to a new animal-based study by researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Their research was published in Advanced Healthcare Materials.

"Our research shows that using our hyaluronic acid hydrogel system at least temporarily stops cartilage degeneration that commonly occurs after injury and causes pain in joints," said the study's senior author, Robert Mauck, PhD, a professor of Orthopaedic Surgery and the director of Penn Medicine's McKay Orthopaedic Research Laboratory. "In addition to pausing cartilage breakdown, we think that applying ...