(Press-News.org) Using a widely known field of mathematics designed mainly to study how digital and other forms of information are measured, stored and shared, scientists at Johns Hopkins Medicine and Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center say they have uncovered a likely key genetic culprit in the development of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

ALL is the most common form of childhood leukemia, striking an estimated 3,000 children and teens each year in the United States alone.

Specifically, the Johns Hopkins team used "information theory," applying an analysis that relies on strings of zeros and ones -- the binary system of symbols common to computer languages and codes -- to identify variables or outcomes of a particular process. In the case of human cancer biology, the scientists focused on a chemical process in cells called DNA methylation, in which certain chemical groups attach to areas of genes that guide genes' on/off switches.

"This study demonstrates how a mathematical language of cancer can help us understand how cells are supposed to behave and how alterations in that behavior affect our health," says Andrew Feinberg, M.D., M.P.H., Bloomberg Distinguished Professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Whiting School of Engineering and Bloomberg School of Public Health. A founder of the field of cancer epigenetics, Feinberg discovered altered DNA methylation in cancer in the 1980s.

Feinberg and his team say that using information theory to find cancer driver genes may be applicable to a wide variety of cancers and other diseases.

Methylation is now recognized as one way DNA can be altered without changing a cell's genetic code. When methylation goes awry in such epigenetic phenomena, certain genes are abnormally turned on or off, triggering uncontrolled cell growth, or cancer.

"Most people are familiar with genetic changes to DNA, namely mutations that change the DNA sequence. Those mutations are like the words that make up a sentence, and methylation is like punctuation in a sentence, providing pauses and stops as we read," says Feinberg. In a search for a new and more efficient way to read and understand the epigenetic code altered by DNA methylation, he worked with John Goutsias, Ph.D., professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at The Johns Hopkins University and Michael Koldobskiy, M.D., Ph.D., pediatric oncologist and assistant professor of oncology at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center.

"We wanted to use this information to identify genes that drive the development of cancer even though their genetic code isn't mutated," says Koldobskiy.

Results of the study's findings, led by Feinberg, Koldobskiy and Goutsias, were published April 15 in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Koldobskiy explains that methylation at a particular gene location is binary -- methylation or no methylation -- and a system of zeros and ones can represent these differences just as they are used to represent computer codes and instructions.

For the study, the Johns Hopkins team analyzed DNA extracted from bone marrow samples of 31 children newly diagnosed with ALL at The Johns Hopkins Hospital and Texas Children's Hospital. They sequenced the DNA to determine which genes, across the entire genome, were methylated and which were not.

Newly diagnosed leukemia patients have billions of leukemia cells in their body, says Koldobskiy.

By assigning zeros and ones to pieces of genetic code that were methylated or unmethylated and using concepts of information theory and computer programs to recognize patterns of methylation, the scientists were able to find regions of the genome that were consistently methylated in patients with leukemia and those without cancer.

They also saw genome regions in the leukemia cells that were more randomly methylated, compared with the normal genome, a signal to scientists that those spots may be specifically linked to leukemia cells compared with normal ones.

One gene, called UHRF1, stood out among other gene regions in leukemia cells that had differences in DNA methylation compared with the normal genome.

"It was a big surprise to find this gene, as its link to prostate and other cancer has been suggested but never identified as a driver of leukemia," says Feinberg.

In normal cells, the protein products of the UHRF1 gene create a biochemical bridge between DNA methylation and DNA packaging, but scientists have not deciphered precisely how alteration of the gene contributes to cancer.

Experiments by the Johns Hopkins team show that laboratory-grown leukemia cells lacking activity of the UHRF1 gene cannot self-renew and perpetuate additional leukemia cells.

"Leukemia cells aim to survive, and the best way to ensure survival is to vary the epigenetics in many genome regions so that no matter what tries to kill the cancer, at least some will survive," says Koldobskiy.

ALL is the most common pediatric cancer, and Koldobskiy says that decades of research on various treatments and the sequence of those treatments have helped clinicians cure most of these leukemias, but relapsed disease remains a leading cause of death from cancer in children.

"This new approach can lead to more rational ways of targeting the alterations that drive this and likely many other forms of cancer," says Koldobskiy.

The Johns Hopkins team plans to use information theory to analyze methylation patterns in other cancers. They also plan to determine whether epigenetic alterations in URFH1 are linked to treatment resistance and disease progression in patients with childhood leukemia.

INFORMATION:

The new research was funded by the National Institutes of Health's National Cancer Institute (R01CA65438), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DP1 DK119129), the National Human Genome Research Institute (R01 HG006282), National Science Foundation (1656201), St. Baldrick's Foundation Fellowship, Unravel Pediatric Cancer and the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation.

In addition to Feinberg, Koldobskiy and Goutsias, contributors to the research include Garrett Jenkinson, Jordi Abante, Varenka Rodriguez DiBlasi, Weiqiang Zhou, Elisabet Pujadas, Adrian Idrizi, Rakel Tryggvadottir, Colin Callahan, Challice Bonifant, Patrick Brown and Hongkai Ji from Johns Hopkins, and Karen R. Rabin from Baylor College of Medicine. END

BOSTON - Recent research links certain cells that line the human airway with different infant diseases. The work, which is published in Cell Reports and was led by investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), could lead to new prevention and treatment strategies for these conditions.

The human airway--from the windpipe to the lungs--is lined with epithelial cells, including a type called pulmonary neuroendocrine cells (PNECs) that communicate with the nervous system and secrete different factors and hormones. Increased numbers and clusters of PNECs have been observed in various breathing-related illnesses, but the cells' roles in health ...

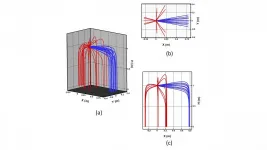

WASHINGTON, April 20, 2021 -- Forensic science includes the analysis of blood backspatter involved in gunshot wounds, but scientific questions about the detailed role of fluids in these situations remained unresolved.

To search for answers about how blood droplets from a gunshot wound can reverse direction while in flight, University of Illinois at Chicago and Iowa State University researchers explored the influence of propellant gases on blood backspatter.

In Physics of Fluids, from AIP Publishing, the researchers report using numeric modeling to capture the behavior of gun muzzle gases and predict the reversal of blood droplet flight, which was captured experimentally. Their experiments also show the breakup of blood droplets, ...

WASHINGTON, April 20, 2021 -- In 2009, music producer Phil Spector was convicted for the 2003 murder of actress Lana Clarkson, who was shot in the face from a very short distance. He was dressed in white clothes, but no bloodstains were found on his clothing -- even though significant backward blood spatter occurred.

How could his clothing remain clean if he was the shooter? This real-life forensic puzzle inspired University of Illinois at Chicago and Iowa State University researchers to explore the fluid physics involved.

In Physics of Fluids, from AIP Publishing, the researchers present theoretical results revealing an interaction of the incoming vortex ring of propellant muzzle gases with backward blood spatter.

A detailed analytical theory of ...

Dietary sugars and gut microbes play a key role in promoting malaria parasite infection in mosquitoes. Researchers in China have uncovered evidence that mosquitoes fed a sugar diet show an increased abundance of the bacterial species Asaia bogorensis, which enhances parasite infection by raising the gut pH level. The study appears April 20 in the journal Cell Reports.

"Our work opens a new path for investigations into the role of mosquito-microbiota metabolic interactions concerning their disease-transmitting potential," says co-senior study author Jingwen Wang of Fudan University in Shanghai, China. "The results may also provide useful insights for the development of preventive strategies for vector ...

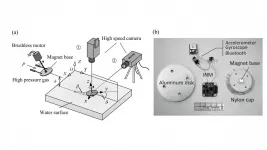

WASHINGTON, April 20, 2021 -- Skipping stones on a body of water is an age-old game, but developing a better understanding of the physics involved is crucial for more serious matters, such as water landings upon reentry of spaceflight vehicles or aircrafts.

In Physics of Fluids, by AIP Publishing, scientists from several universities in China reveal several key factors that influence the number of bounces a skipping stone or landing aircraft will undergo when hitting the water.

The study involved theoretical modeling and a simple experimental setup using a model stone to gather data in real time. The investigators used an aluminum disk as a stand-in for the stone and designed a launching mechanism that utilized a puff of air from a compressor ...

What The Study Did: Researchers investigated the association of burnout at an academic medical center with clinician type, sex, work culture and use of electronic health records.

Authors: Eugenia McPeek-Hinz, M.D., M.S., of the Duke University Health System in Durham, North Carolina, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5686)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, ...

The worldwide adoption of biotechnologies to improve crop production has stalled, putting global food security at risk, according to an international team of researchers led by the University of Birmingham.

The group, which includes economists, plant breeders and plant scientists, is calling on governments worldwide to put in place policies and regulations that will drive progress in this area.

In an article published in the 25th anniversary edition of Trends in Plant Science, the group, which includes researchers from Australia, Canada and India, also argues that societal acceptance of technologies such as gene editing is a big barrier to adoption. They urge the scientific community to work harder to convince the public and governments of the value of adopting ...

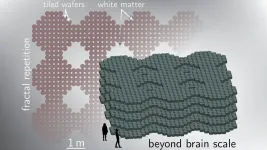

WASHINGTON, April 20, 2021 -- As artificial intelligence has attracted broad interest, researchers are focused on understanding how the brain accomplishes cognition so they can construct artificial systems with general intelligence comparable to humans' intelligence.

Many have approached this challenge by using conventional silicon microelectronics in conjunction with light. However, the fabrication of silicon chips with electronic and photonic circuit elements is difficult for many physical and practical reasons related to the materials used for the components.

In Applied Physics Letters, by AIP Publishing, researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology propose an approach to large-scale artificial intelligence that ...

INDIANAPOLIS -- Patients who suffer from traumatic brain injuries (TBI) often need a great deal of healthcare services after the injury, but the extent of care utilization is unknown. A new study from research scientists affiliated with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Regenstrief Institute and IUPUI is one of the first to analyze how much care TBI patients use and identify areas of unmet need.

"There is not a lot of information about traumatic brain injury care utilization available," said primary study author Johanne Eliacin, PhD, a Regenstrief research scientist and core investigator at the VA Health Services Research and Development Center for Health Information at Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical ...

A recent study suggests that preserving physical and mental health helps older adults experiencing cognitive impairment stave off declines in cognitive engagement.

"We found that declines in physical and mental health were associated with more pronounced cognitive disengagement," says Shevaun Neupert, corresponding author of the study and a professor of psychology at North Carolina State University. "The impact of declines in physical health was particularly pronounced for study participants who had more advanced cognitive impairment to begin with."

There's ...