(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. -- When marine biologist Eleanor Caves of the University of Exeter thinks back to her first scuba dives, one of the first things she recalls noticing is that colors seem off underwater. The vivid reds, oranges, purples and yellows she was used to seeing in the sunlit waters near the surface look increasingly dim and drab with depth, and before long the whole ocean loses most of its rainbow leaving nothing but shades of blue.

"The thing that always got me about diving was what happens to people's faces and lips," said her former Ph.D. adviser Sönke Johnsen, a biology professor at Duke University. "Everybody has a ghastly sallow complexion."

Which got the researchers to thinking: In the last half-century, some fish have been shifting into deeper waters, and climate change is likely to blame. One study found that fish species off the northeastern coast of the United States descended more than one meter per year between 1968 and 2007, in response to a warming of only about one degree Celsius.

Could such shifts make the color cues fish rely on for survival harder to see?

Previous research suggests it might. Scientists already have evidence that fish have a harder time discerning differences in each other's hues and brightness in waters made murkier by other causes, such as erosion or nutrient runoff.

As an example, the authors cite studies of three-spined sticklebacks that breed in the shallow coastal waters of the Baltic Sea, where females choose among males -- who care for the eggs -- based on the redness of their throats and bellies. But algal blooms can create cloudy conditions that make it harder to see, which tricks females into mating with less fit males whose hatchlings don't make it.

The turbidity makes it harder for a male to prove he's a worthy mate by interfering with females' ability to distinguish subtle gradations of red or orange, Johnsen said. "For any poor fish that has beautiful red coloration on his body, now it's like, 'well, you're just going to have to take my word for it.'"

Other studies have shown that, for cichlid fish in Africa's Lake Victoria, where species rely on their distinctive colors to recognize their own kind, pollution can reduce water clarity to a point where they lose the ability to tell each other apart and start mating every which way.

The researchers say the same communication breakdown plaguing fish in turbid waters is likely happening to species that are being pushed to greater depths. And interactions with would-be mates aren't the only situations that could be prone to confusion. Difficulty distinguishing colors could also make it harder for fish to locate prey, recognize rivals, or warn potential predators that they are dangerous to eat.

In a study published April 21 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Caves and Johnsen used mathematical models to determine what the colors of the underwater world might look like as fish in the uppermost layer of the ocean shift to new depths.

They were able to show that, while the surface waters may be bursting with color, descending by just 30 meters shrinks the palette considerably.

"It's like going back to the days of black and white TV," Johnsen said.

When sunlight hits an object, some wavelengths are absorbed and others bounce off. It's the wavelengths that are reflected back that make a red fish look red, or a blue fish blue. But a fish sporting certain colors at the surface will start to look different as it swims deeper because the water filters out or absorbs some wavelengths sooner than others.

The researchers were surprised to find that, especially for shallow-water species such as those that live in and around coral reefs, it doesn't take much of a downward shift to have a dramatic effect on how colors appear.

"You really don't have to go very far from the surface to notice a big impact," said Caves, who will be starting as an assistant professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, this fall.

Precisely which colors lose their luster first, and how quickly that happens as you go down, depends on what depths a species typically inhabits and how much deeper they are forced to go, as well as the type of environment they live in -- whether it's, say, the shallow bays or rocky shores of the Atlantic, or a tropical coral reef.

In clear ocean water, red is the first color to dull and disappear. "That's important because so many species use red signals to attract mates or deter enemies," Johnsen said.

The team predicts that some species will be more vulnerable than others. Take, for instance, fish that can't take the edge off the heat by relocating toward the poles of the planet. Particularly in semi-enclosed waters such as the Mediterranean and Black seas or the Gulf of Mexico, or in coral reefs, which are stuck to the sea bed -- these species will have no option but to dive deeper to keep their cool, Caves said.

As a next step, they hope to test their ideas in the coral reefs around the island of Guam, where butterflyfishes and fire gobies use their vivid color patterns to recognize members of their own species and woo mates.

"The problem is only accelerating," Caves said. By the end of this century, it's possible that sea surface temperatures will have heated up another 4.8 degrees Celsius, or an increase of 8.6 degrees Fahrenheit, compared to the 1896-2005 average.

And while warming is happening faster at the poles, "tropical waters are feeling the effects too," Caves said.

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement (No 793454).

CITATION: "The Sensory Impacts of Climate Change: Bathymetric Shifts and Visually Mediated Interactions in Aquatic Species," Eleanor Caves and Sönke Johnsen. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, April 21, 2021. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2021.0396

Researchers at GMI - Gregor Mendel Institute of Molecular Plant Biology of the Austrian Academy of Sciences - and the John Innes Centre, Norwich, United Kingdom, determine that gene-regulatory mechanisms at an early embryonic stage govern the flowering behavior of Arabidopsis later in development. The paper is published in the journal PNAS.

How do early life events shape the ability of organisms to respond to environmental cues later in their life? Can such phenomena be explained at the mechanistic level? GMI group leader and co-corresponding author Michael Nodine counters these questions with a clear statement: "Our research demonstrates that gene-regulatory mechanisms established in early embryos forecast events that have major ...

UC Riverside engineers are developing methods to estimate the impact of California's destructive wildfires on air quality in neighborhoods affected by the smoke from these fires. Their research, funded by NASA and the results published in Atmospheric Pollution Research, fills in the gaps in current methods by providing air quality information at the neighborhood scales required by public health officials to make health assessments and evacuation recommendations.

Measurements of air quality depend largely on ground-based sensors that are typically spaced many miles apart. Determining how healthy it is to breathe air is straightforward in the vicinity of the sensors but becomes unreliable in areas in between sensors.

Akula Venkatram, a professor of mechanical engineering in UC Riverside's ...

Much of common pharmaceutical development today is the product of laborious cycles of tweaking and optimization. In each drug, a carefully concocted formula of natural and synthetic enzymes and ingredients works together to catalyze a desired reaction. But in early development, much of the process is spent determining what quantities of each enzyme to use to ensure a reaction occurs at a specific speed.

New collaborative research from Northwestern University could expedite, or even eliminate, the need for scientists to manually adjust bioproduction reaction conditions at all. Using ideas conceived by graduate students across three labs, Northwestern researchers developed technology that allows microbes to produce drugs with feedback control systems, dialing down or amping up ...

Cisgender sexual minority men and transgender women are aware of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a daily pill for HIV-negative people to prevent HIV infection, but few are currently taking it, according to researchers at Rutgers.

The study, published in the journal AIDS and Behavior, surveyed 202 young sexual minority men and transgender women - two high-priority populations for HIV prevention - to better understand why some were more likely than others to be taking PrEP.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sexual minority men are the community most impacted by HIV, making ...

Skoltech scientists in collaboration with researchers from the University of Arizona and the Los Alamos National Laboratory have developed an approach that allows power grids to return to stability fast after demand response perturbation. Their research at the crossroads of demand response, smart grids, and power grid control was published in the journal Applied Energy.

Power grids are complex systems that manage the generation, transmission and distribution of electrical power to consumers, also called loads. As it is not possible to store electrical energy along the transmission lines, grid operators must ensure, ideally at all times, the balance between production and consumption of electrical energy, i.e. the stability of power grids. While it is essential ...

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) have developed a new mathematical model for predicting how epidemics such as COVID-19 spread. This model not only accounts for individuals' varying biological susceptibility to infection but also their levels of social activity, which naturally change over time. Using their model, the team showed that a temporary state of collective immunity--which they termed "transient collective immunity"--emerged during the early, fast-paced stages of the epidemic. However, subsequent "waves," ...

BOSTON - Legislation currently under consideration in the U.S. Congress would increase regulatory oversight of certain diagnostic tests, and a new study by researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and colleagues from several other institutions demonstrates that its potential impact will depend on key details in the bill's final language. This study, published in JCO Oncology Practice, offers the first evidence-based analysis of how new rules proposed for the regulation of laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) could affect health care costs in the United States.

"The idea of having more oversight of LDTs is justified," says Jochen Lennerz, MD, PhD, medical director of the MGH Center for Integrated Diagnostics (CID) and the study's senior author. ...

April 21, 2021 - Consuming a diet high in pro-inflammatory foods - including foods that contain refined carbohydrates and sugar as well as polyunsaturated fats - may be associated with increased odds of developing testosterone deficiency among men, suggests a study in The Journal of Urology®, Official Journal of the American Urological Association (AUA). The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

The risk of testosterone deficiency is greatest in men who are obese and consume a refined diet that scores high on the dietary inflammatory index (DII), according to the new research by Qiu Shi, MD, Zhang Chichen, MD, and colleagues of ...

A national strategy to ensure that families have access to food could revolutionize Canada's farms, according to a new study from Simon Fraser University's Food Systems Lab. The study proposes implementing a "right to food" framework that would support the needed funding, infrastructure, and stability that can reduce losses of edible food at the farm, while creating better access to local foods for consumers.

The study, published in the journal Resources, Conservation and Recycling, looked at the reasons for on-farm losses of edible food. Approximately 14 per cent of the world's food is lost before it ever reaches store shelves. In Canada, 35.5 million metric tonnes of food are lost or wasted annually, ...

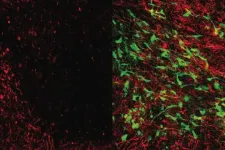

A one-time injection of an experimental stem cell therapy can repair brain damage and improve memory function in mice with conditions that replicate human strokes and dementia, a new UCLA study finds.

Dementia can arise from multiple conditions, and it is characterized by an array of symptoms including problems with memory, attention, communication and physical coordination. The two most common causes of dementia are Alzheimer's disease and white matter strokes -- small strokes that accumulate in the connecting areas of the brain.

"It's a vicious cycle: ...