(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA--(April 22, 2021) Spinal cord nerve cells branching through the body resemble trees with limbs fanning out in every direction. But this image can also be used to tell the story of how these neurons, their jobs becoming more specialized over time, arose through developmental and evolutionary history. Salk researchers have, for the first time, traced the development of spinal cord neurons using genetic signatures and revealed how different subtypes of the cells may have evolved and ultimately function to regulate our body movements.

The findings, published in the journal Science on April 23, 2021, offer researchers new ways of classifying and tagging subsets of spinal cord cells for further study, using genetic markers that differentiate branches of the cells' family tree.

"A study like this provides the first molecular handles for scientists to go in and study the function of spinal cord neurons in a much more precise way than they ever have before," says senior author of the study Samuel Pfaff, Salk Professor and the Benjamin H. Lewis Chair. "This also has implications for treating spinal cord injuries."

Spinal neurons are responsible for transmitting messages between the spinal cord and the rest of the body. Researchers studying spinal neurons have typically classified the cells into "cardinal classes," which describe where in the spinal cord each type of neuron first appears during fetal development. But, in an adult, neurons within any one cardinal class have varied functions and molecular characteristics. Studying small subsets of these cells to tease apart their diversity has been difficult. However, understanding these subset distinctions is crucial to helping researchers understand how the spinal cord neurons control movements and what goes awry in neurogenerative diseases or spinal cord injury.

"It's been known for a long time that the cardinal classes, as useful as they are, are incomplete in describing the diversity of neurons in the spinal cord," says Peter Osseward, a graduate student in the Pfaff lab and co-first author of the new paper, along with former graduate student Marito Hayashi, now a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University.

Pfaff, Osseward and Hayashi turned to single-cell RNA sequencing technologies to analyze differences in what genes were being activated in almost 7,000 different spinal neurons from mice. They used this data to group cells into closely related clusters in the same way that scientists might group related organisms into a family tree.

The first major gene expression pattern they saw divided spinal neurons into two branches: sensory-related neurons (which carry information about the environment through the spinal cord) and motor-related neurons (which carry motor commands through the spinal cord). This suggests that, in an ancient organism, one of the first steps in spinal cord evolution may have been a division of labor of spinal neurons into motor versus sensory roles, Pfaff says.

When the team analyzed the next branches in the family tree, they found that the sensory-related neurons then split into excitatory and inhibitory neurons--a division that describes how the neuron sends information. But when the researchers looked at motor-related neurons, they found a more surprising division: the cells clumped into two distinct groups based on a new genetic marker. When the team stained cells belonging to each group in the spinal cord, it became clear that the markers differentiated neurons based on whether they had long-range or short-range connections in the body. Further experiments revealed that the genetic patterns specific to long-range and short-range properties were common across all the cardinal classes tested.

"The assumption in the field was that the genetic rules of specifying long-range versus short-range neurons would be specific to each cardinal class," say Osseward and Hayashi. "So it was really interesting to see that it actually transcended cardinal class."

The observation was more than just interesting--it turned out to be useful as well. Previously, it might have taken many different genetic tags to narrow in on one particular neuron type that a researcher wanted to study. Using this many markers is technically challenging and largely prevented researchers from studying just one subtype of spinal cord neuron at a time.

With the new rules, just two tags--a previously known marker for cardinal class and the newly discovered genetic marker for long-range or short-range properties--can be used to flag very specific populations of neurons. This is useful, for instance, in studying which groups of neurons are affected by a spinal cord injury or neurodegenerative disease and, eventually, how to regrow those particular cells.

The evolutionary origin of the spinal neuron family tree studied in the new paper is likely very ancient because the genetic markers they discovered are conserved across many species, the researchers say. So, although they didn't study spinal neurons from animals other than mice, they predict that the same genetic patterns would be seen in most living animals with spinal cords.

"This is primordial stuff, relevant for everything from amphibians to humans," says Pfaff. "And in the context of evolution, these genetic patterns tell us what kind of neurons might have been found in some of the very earliest organisms."

INFORMATION:

Other authors of the study were Neal Amin, Benjamin Temple, Bianca Barriga, Lukas Bachmann, Fernando Beltran, Miriam Gullo, Robert Clark and Shawn Driscoll of Salk; and Jeffrey Moore of Harvard University. The work was supported by grants from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation, the Sol Goldman Charitable Trust, and the National Institutes of Health.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

Every cure has a starting point. The Salk Institute embodies Jonas Salk's mission to dare to make dreams into reality. Its internationally renowned and award-winning scientists explore the very foundations of life, seeking new understandings in neuroscience, genetics, immunology, plant biology and more. The Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark: small by choice, intimate by nature and fearless in the face of any challenge. Be it cancer or Alzheimer's, aging or diabetes, Salk is where cures begin. Learn more at: salk.edu.

In two landmark studies, researchers have used cutting-edge genomic tools to investigate the potential health effects of exposure to ionizing radiation, a known carcinogen, from the 1986 accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in northern Ukraine. One study found no evidence that radiation exposure to parents resulted in new genetic changes being passed from parent to child. The second study documented the genetic changes in the tumors of people who developed thyroid cancer after being exposed as children or fetuses to the radiation released by the accident.

The findings, published around the ...

Researchers have found that a natural molecule can effectively block the binding of a subset of human antibodies to SARS-CoV-2. The discovery may help explain why some COVID-19 patients can become severely ill despite having high levels of antibodies against the virus.

In their research, published in Science Advances today (22 April 2021), teams from the Francis Crick Institute, in collaboration with researchers at Imperial College London, Kings College London and UCL (University College London), found that biliverdin and bilirubin, natural molecules present in the body, can suppress the ...

Researchers have identified another potential target for neutralizing antibodies on the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein that is masked by metabolites in the blood. As a result of this masking, the target may be inaccessible to antibodies, because they must compete with metabolite molecules to bind to the otherwise open region, the study authors speculate. This competitive binding activity may represent another method of immune evasion by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Although further validation work is needed, the findings suggest that strategies to unmask this region - thus making it more visible and accessible to antibodies - may help lead to new vaccine designs. ...

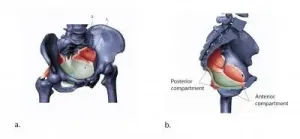

AUSTIN, Texas -- Despite advances in medicine and technology, childbirth isn't likely to get much easier on women from a biological perspective.

Engineers at The University of Texas at Austin and University of Vienna revealed in new research a series of evolutionary trade-offs that have created a near-perfect balance between supporting childbirth and keeping organs intact on a day-to-day basis. Human reproduction is unique because of the comparatively tight fit between the birth canal and baby's head, and it is likely to stay that way because of these competing biological imperatives.

The size of the pelvic floor and canal is key to keeping this balance. These opposing duties have constrained the ability of the pelvic floor to evolve over time to make childbirth easier because doing ...

Not all cancerous tumors are created equal. Some tumors, known as "hot" tumors, show signs of inflammation, which means they are infiltrated with T cells working to fight the cancer. Those tumors are easier to treat, as immunotherapy drugs can then amp up the immune response.

"Cold" tumors, on the other hand, have no T-cell infiltration, which means the immune system is not stepping in to help. With these tumors, immunotherapy is of little use.

It's the latter type of tumor that researchers Michael Knitz and radiation oncologist and University of Colorado Cancer Center member Sana Karam, MD, PhD, address in new research published this week in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer. Working with mouse models in Karam's specialty area of head and neck cancers, Knitz and ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- As NASA's Perseverance rover begins its search for ancient life on the surface of Mars, a new study suggests that the Martian subsurface might be a good place to look for possible present-day life on the Red Planet.

The study, published in the journal Astrobiology, looked at the chemical composition of Martian meteorites -- rocks blasted off of the surface of Mars that eventually landed on Earth. The analysis determined that those rocks, if in consistent contact with water, would produce the chemical energy needed to support microbial communities similar to those that survive in the unlit depths of the Earth. Because these meteorites may be representative ...

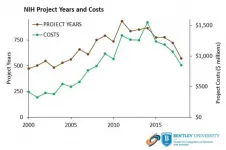

The unprecedented development of COVID-19 vaccines less than a year after discovery of this virus was enabled by more than $17 billion of research on vaccine technologies funded by the NIH prior to the pandemic, according to new research from Bentley University's Center for Integration of Science and Industry. The article, titled "NIH funding for vaccine readiness before the COVID-19 pandemic," demonstrates the critical role this broad foundation of government-funded research plays in ensuring vaccine readiness.

The report, published today in the journal Vaccine, ...

DALLAS - April 22, 2021 - Being Black or Hispanic, living in high-poverty neighborhoods, and having Medicaid or no insurance coverage are associated with higher mortality in men and women under 40 with cancer, a review by UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers found.

"Survival is not different because of biology. It's not different because of patient-level factors," says Caitlin Murphy, Ph.D., lead author of the study and an assistant professor of population and data sciences and internal medicine at UT Southwestern. "No matter which way we looked at the data, we still saw consistent and alarming differences in survival by race - and these are teens and young adults."

Other findings based on an ...

Machine learning could provide up an extra hour of warning time for debris flows along the Illgraben torrent in Switzerland, researchers report at the Seismological Society of America (SSA)'s 2021 Annual Meeting.

Debris flows are mixtures of water, sediment and rock that move rapidly down steep hills, triggered by heavy precipitation and often containing tens of thousands of cubic meters of material. Their destructive potential makes it important to have monitoring and warning systems in place to protect nearby people and infrastructure.

In her presentation at SSA, Ma?gorzata Chmiel of ETH Zürich described a machine learning approach to detecting and alerting against debris flows for the Illgraben torrent, a site in the European Alps that experiences significant debris flows and torrential ...

It seems like a smooth slab of stainless steel, but look a little closer, and you'll see a simplified cross-section of the Los Angeles sedimentary basin.

Caltech researcher Sunyoung Park and her colleagues are printing 3D models like the metal Los Angeles proxy to provide a novel platform for seismic experiments. By printing a model that replicates a basin's edge or the rise and fall of a topographic feature and directing laser light at it, Park can simulate and record how seismic waves might pass through the real Earth.

In her presentation at the Seismological Society of America (SSA)'s 2021 Annual Meeting, Park explained why these physical models can address some of the drawbacks of numerical modeling of ground motion in some cases.

Small-scale, complex structures in ...