Ancient Indigenous forest gardens promote a healthy ecosystem: SFU study

The researchers say this study marks the first time forest gardens have been studied in North America

2021-04-22

(Press-News.org) A new study by Simon Fraser University historical ecologists finds that Indigenous-managed forests--cared for as "forest gardens"--contain more biologically and functionally diverse species than surrounding conifer-dominated forests and create important habitat for animals and pollinators. The findings are published today in Ecology and Society.

According to researchers, ancient forests were once tended by Ts'msyen and Coast Salish peoples living along the north and south Pacific coast. These forest gardens continue to grow at remote archaeological villages on Canada's northwest coast and are composed of native fruit and nut trees and shrubs such as crabapple, hazelnut, cranberry, wild plum, and wild cherries. Important medicinal plants and root foods like wild ginger and wild rice root grow in the understory layers.

"These plants never grow together in the wild," says Chelsey Geralda Armstrong, an SFU Indigenous Studies assistant professor and the study lead researcher. "It seemed obvious that people put them there to grow all in one spot - like a garden. Elders and knowledge holders talk about perennial management all the time."

"It's no surprise these forest gardens continue to grow at archaeological village sites that haven't yet been too severely disrupted by settler-colonial land-use."

Ts'msyen and Coast Salish peoples' management practices challenge the assumption that humans tend to overturn or exhaust the ecosystems they inhabit. This research highlights how Indigenous peoples not only improved the inhabited landscape, but were also keystone builders, facilitating the creation of habitat in some cases. The findings provide strong evidence that Indigenous management practices are tied to ecosystem health and resilience.

"Human activities are often considered detrimental to biodiversity, and indeed, industrial land management has had devastating consequences for biodiversity," says Jesse Miller, study co-author, ecologist and lecturer at Stanford University. "Our research, however, shows that human activities can also have substantial benefits for biodiversity and ecosystem function. Our findings highlight that there continues to be an important role for human activities in restoring and managing ecosystems in the present and future."

Forest gardens are a common management regime identified in Indigenous communities around the world, especially in tropical regions. Armstrong says the study is the first time forest gardens have been studied in North America -- showing how important Indigenous peoples are in the maintenance and defence of some of the most functionally diverse ecosystems on the Northwest Coast.

"The forest gardens of Kitselas Canyon are a testament to the long-standing practice of Kitselas people shaping the landscape through stewardship and management," says Chris Apps, director, Kitselas Lands & Resources Department. "Studies such as this reconnect the community with historic resources and support integration of traditional approaches with contemporary land-use management while promoting exciting initiatives for food sovereignty and cultural reflection."

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-22

In 2005, an ultramarathon runner ran continuously 560 kilometers (350 miles) in 80 hours, without sleeping or stopping. This distance was roughly 324,000 times the runner's body length. Yet this extreme feat pales in comparison to the relative distances that fruit flies can travel in a single flight, according to new research from Caltech.

Caltech scientists have now discovered that fruit flies can fly up to 15 kilometers (about 9 miles) in a single journey--6 million times their body length, or the equivalent of over 10,000 kilometers for the average human. In comparison to body length, this is further than many migratory species of birds can fly in a day. To discover this, the team conducted experiments in a dry lakebed ...

2021-04-22

In a worldwide study of 2,100 pregnant women, those who contracted COVID-19 during pregnancy were 20 times more likely to die than those who did not contract the virus.

UW Medicine and University of Oxford doctors led this first-of-its-kind study, published today in JAMA Pediatrics. The investigation involved more than 100 researchers and pregnant women from 43 maternity hospitals in 18 low-, middle- and high-income nations; 220 of the women received care in the United States, 40 at UW Medicine. The research was conducted between April and August of 2020.

The study is unique because each woman affected by COVID-19 was compared with two uninfected pregnant women who gave birth during the same span in the same hospital.

Aside ...

2021-04-22

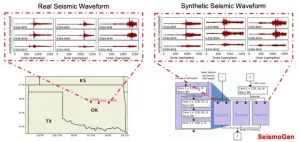

LOS ALAMOS, N.M., April 22, 2021--A new machine-learning model that generates realistic seismic waveforms will reduce manual labor and improve earthquake detection, according to a study published recently in JGR Solid Earth.

"To verify the e?cacy of our generative model, we applied it to seismic ?eld data collected in Oklahoma," said Youzuo Lin, a computational scientist in Los Alamos National Laboratory's Geophysics group and principal investigator of the project. "Through a sequence of qualitative and quantitative tests and benchmarks, we saw that our model can generate high-quality synthetic waveforms and improve machine learning-based earthquake detection algorithms."

Quickly and accurately detecting earthquakes can be a challenging task. Visual detection done ...

2021-04-22

Photocatalysts are useful materials, with a myriad of environmental and energy applications, including air purification, water treatment, self-cleaning surfaces, pollution-fighting paints and coatings, hydrogen production and CO2 conversion to sustainable fuels.

An efficient photocatalyst converts light energy into chemical energy and provides this energy to a reacting substance, to help chemical reactions occur.

One of the most useful such materials is knows as titanium oxide or titania, much sought after for its stability, effectiveness as a photocatalyst ...

2021-04-22

Researchers have determined a way to potentially minimize or eliminate scarring in wounded skin, by further decoding the scar-promoting role of a specific class of dermal fibroblast cells in mice. By preventing these cells from expressing the transcription factor Engrailed-1 (En-1), Shamik Mascharak and colleagues reprogrammed these cells to take on a different identity, capable of regenerating wounded skin - including the restoration of structures such as hair follicles and sweat glands that are absent in scarred skin tissue. With further development and testing, their discovery could lead to therapies to reduce or completely avoid scarring ...

2021-04-22

A new multi-model analysis suggests that China will need to reduce its carbon emissions by over 90% and its energy consumption by almost 40%, in order to meet the more ambitious target set by the 2016 Paris Agreement. The Agreement called for no more than a 1.5°Celsius (C) global temperature rise by 2050. These results provide a clear directive for China to deploy multiple strategies at once for long-term emission mitigation, the authors say. The findings also highlight the need for more research on the economic consequences of working toward a 1.5°C warming limit, arguing that current studies are far from adequate to inform the sixth assessment report (AR 6) on climate change planned for release by the United Nations' Intergovernmental ...

2021-04-22

A new study of nearly five million live births recorded in California from 2001 to 2012 found that babies born to mothers diagnosed with cannabis use disorders at delivery were more likely to experience negative health outcomes, including preterm birth and low birth weight, compared to babies born to mothers without a cannabis use disorder diagnosis. The analysis, published today in Addiction and funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of the National Institutes of Health, adds to a growing body of evidence that prenatal exposure to cannabis (marijuana) may be associated with poor birth outcomes, and sheds light on infant health one year after birth.

Recent studies have shown the ...

2021-04-22

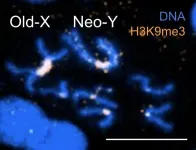

Males may have shorter lifespans than females due to repetitive sections of the Y chromosome that create toxic effects as males get older. These new findings appear in a study by Doris Bachtrog of the University of California, Berkeley published April 22 in PLOS Genetics.

In humans and other species with XY sex chromosomes, females often live longer than males. One possible explanation for this disparity may be repetitive sequences within the genome. While both males and females carry these repeat sequences, scientists have suspected that the large number of repeats ...

2021-04-22

A study of almost 5 million live births in California by researchers at the Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health and Human Longevity Science at University of California San Diego reports that babies born to mothers diagnosed with cannabis use disorder were more likely to experience negative health outcomes, such as preterm birth and low birth weight, than babies born to mothers without a cannabis use disorder diagnosis.

The findings are published online in the April 22, 2021 issue of the journal Addiction. The National Institute on Drug Abuse, part of the National Institutes of Health, funded the study.

Cannabis use disorder is a diagnostic term with specific criteria that defines continued cannabis use despite ...

2021-04-22

A natural compound previously demonstrated to counteract aspects of aging and improve metabolic health in mice has clinically relevant effects in people, according to new research at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

A small clinical trial of postmenopausal women with prediabetes shows that the compound NMN (nicotinamide mononucleotide) improved the ability of insulin to increase glucose uptake in skeletal muscle, which often is abnormal in people with obesity, prediabetes or Type 2 diabetes. NMN also improved expression of genes that are involved in muscle structure and remodeling. However, the treatment did not lower blood glucose or blood pressure, improve blood lipid profile, increase insulin sensitivity in the liver, reduce fat ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Ancient Indigenous forest gardens promote a healthy ecosystem: SFU study

The researchers say this study marks the first time forest gardens have been studied in North America