(Press-News.org) New findings detailing the world's first-of-its-kind estimate of how many people live in high-altitude regions, will provide insight into future research of human physiology.

Dr. Joshua Tremblay, a postdoctoral fellow in UBC Okanagan's School of Health and Exercise Sciences, has released updated population estimates of how many people in the world live at a high altitude.

Historically the estimated number of people living at these elevations has varied widely. That's partially, he explains, because the definition of "high altitude" does not have a fixed cut-off.

Using novel techniques, Dr. Tremblay's publication in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences confirms there are about 81.6 million people who live 2,500 metres above sea level. From a physiological perspective, researchers typically use 2,500 metres as an altitude benchmark for their work.

Dr. Trembly says an important part of his study was presenting population data at 500-metre intervals. And while he says the 81 million is a staggering number, it is also important to note that by going to 1,500 metres that number jumps to more than 500 million.

"To understand the impact of life at high altitude on human physiology, adaption, health and disease, it is imperative to know how many people live at high altitude and where they live," says Dr. Tremblay.

Earlier research relied on calculating percentages of inconsistent population data and specific country-level data that has been unavailable. To address this, Dr. Tremblay combined geo-referenced population and elevation data to create global and country-level estimates of humans living at high altitude.

"The majority of high-altitude research is based upon lowlanders from western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic countries who ascend to high altitude to conduct their research," says Dr. Tremblay. "Yet, there are populations who have successfully lived at high altitudes for thousands of years and who are facing increasing pressures."

Living at high altitude presents major stressors to human physiology, he explains. For example, low air pressure at high altitude makes it more difficult for oxygen to enter a person's vascular systems.

"When low-landers travel to high altitudes our bodies develop inefficient physiological responses, which we know as altitude sickness," he says. "However, the people we studied have acquired the ability to thrive at extremely high altitudes. Their experiences can inform the diagnosis and treatment of disease for all humans, while also helping us understand how to enhance the health and well-being of high-altitude populations."

With only a fraction of the world's high-altitude residents being studied, the understanding of the location and size of populations is a critical step towards understanding the differences arising from life at high altitude.

Dr. Tremblay notes it's not just a case of understanding how these populations have survived for generations, but also how they thrive living in such extreme conditions. Especially as climate change continues to impact, not only the air they breathe, but every aspect of their daily lives.

"We tend to think of climate change as a problem for low-altitude, coastal populations, but melting snow, glaciers and extreme weather events limit water and agriculture resources," he explains. "High-altitude residents are on the frontlines of climate change. We need to expand this vital research so we can understand the effects of climate change and unavoidable low levels of oxygen on high-altitude populations."

INFORMATION:

New research reveals a genetic quirk in a small species of songbird in addition to its ability to carry a tune. It turns out the zebra finch is a surprisingly healthy bird.

A study published today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reveals that zebra finches and other songbirds have a low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) gene surprisingly different than other vertebrates.

The function of LDLR, which is responsible for cellular uptake of LDL-bound cholesterol, or "bad cholesterol," has been thought to be conserved across vertebrates. OHSU scientists found that in the case ...

Stomata, formed by a pair of kidney-shaped guard cells, are tiny pores in leaves. They act like mouths that plants use to "eat" and "breathe." When they open, carbon dioxide (CO2) enters the plant for photosynthesis and oxygen (O2) is released into the atmosphere. At the same time as gases pass in and out, a great deal of water also evaporates through the same pores by way of transpiration.

These "mouths" close in response to environmental stimuli such as high CO2 levels, ozone, drought and microbe invasion. The protein responsible for closing these "mouths" is an anion channel, called SLAC1, which moves negatively charged ions across the guard cell membrane to reduce turgor pressure. Low pressure causes the guard cells to collapse and subsequently the stomatal pore to ...

(Boston)--Lung carcinomas are the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States and worldwide. Lung squamous cell carcinomas (non-small cell lung cancers that arise in the bronchi of the lungs and make up approximately 30 percent of all lung cancers) are poorly understood, particularly with respect to the cell type and signals that contribute to disease onset.

According to the researchers, treatments for lung squamous cell carcinomas are limited and research into the etiology of the disease is required to create new ways to treat it.

"Our study offers insight into how damage ...

A multi-institutional team of researchers has identified both the genetic abnormalities that drive pre-cancer cells into becoming an invasive type of head and neck cancer and patients who are least likely to respond to immunotherapy.

"Through a series of surprises, we followed clues that focused more and more tightly on specific genetic imbalances and their role in the effects of specific immune components in tumor development," said co-principal investigator Webster Cavenee, PhD, Distinguished Professor Emeritus at University of California San Diego School of Medicine.

"The genetic ...

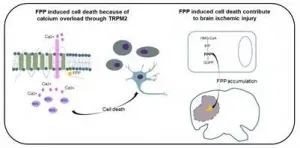

A vital intermediate in normal cell metabolism is also, in the right context, a trigger for cell death, according to a new study from Wanli Liu and Yonghui Zhang of Tsinghua University, and Yong Zhang of Peking University in Beijing, publishing 26th April 2021 in the open access journal PLOS biology. The discovery may contribute to a better understanding of the damage caused by stroke, and may offer a new drug target to reduce that damage.

Farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) is an intermediate in the mevalonate pathway, a series of biochemical reactions in every cell that contributes to protein synthesis, energy production, and construction of cell membranes. During a search for regulators of immune cell function, the authors unexpectedly discovered that FPP, when present at high concentrations ...

Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 may be at risk of developing heart failure even if they do not have a previous history of heart disease or cardiovascular risk factors, a new Mount Sinai study shows.

Researchers say that while these instances are rare, doctors should be aware of this potential complication. The study, published in the April 26 online issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, may prompt more monitoring of heart failure symptoms among patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

"This is one of the largest studies to date to specifically capture instances of new heart failure diagnosis among patients hospitalized ...

Skid marks left by cars are often analyzed for their impression patterns, but they often don't provide enough information to identify a specific vehicle. UCF Chemistry Associate Professor Matthieu Baudelet and his forensics team at the National Center for Forensic Science, which was established at UCF in 1997, may have just unlocked a new way to collect evidence from those skid marks.

The team recently published a study in the journal Applied Spectroscopy that details how they are classifying the chemical profile of tires to link vehicles back to potential crime ...

A genome by itself is like a recipe without a chef - full of important information, but in need of interpretation. So, even though we have sequenced genomes of our nearest extinct relatives - the Neanderthals and the Denisovans - there remain many unknowns regarding how differences in our genomes actually lead to differences in physical traits.

"When we're looking at archaic genomes, we don't have all the layers and marks that we usually have in samples from present-day individuals that help us interpret regulation in the genome, like RNA or cell structure," said David Gokhman, a postdoctoral fellow in biology at Stanford University.

"We ...

Gossip is often considered socially taboo and dismissed for its negative tone, but a Dartmouth study illustrates some of its merits. Gossip facilitates social connection and enables learning about the world indirectly through other people's experiences.

Gossip is not necessarily spreading rumors or saying bad things about other people but can include small talk in-person or online, such as having a private chat during a Zoom meeting. Prior research has found that approximately 14% of people's daily conversations are gossip, and primarily neutral in tone.

"Gossip is ...

Powered flight in animals -that uses flapping wings to generate thrust- is a very energetically demanding mode of locomotion that requires many anatomical and physiological adaptations. In fact, the capability to develop it has only appeared four times in the evolutionary history of animals: on insects, pterosaurs, birds and bats.

A research paper published in 2020 in the scientific journal Current Biology concluded that, apart from birds -the only living descendants of dinosaurs-, powered flight would have originated independently in other three groups of dinosaurs. A conclusion that makes a great impact, as it increases the number of vertebrates that would have developed this costly mode of locomotion, ...