(Press-News.org) A genome by itself is like a recipe without a chef - full of important information, but in need of interpretation. So, even though we have sequenced genomes of our nearest extinct relatives - the Neanderthals and the Denisovans - there remain many unknowns regarding how differences in our genomes actually lead to differences in physical traits.

"When we're looking at archaic genomes, we don't have all the layers and marks that we usually have in samples from present-day individuals that help us interpret regulation in the genome, like RNA or cell structure," said David Gokhman, a postdoctoral fellow in biology at Stanford University.

"We just have the naked DNA sequence, and all we can really do is stare at it and hope one day we'd be able to understand what it means," he said.

Motivated by such hopes, a team of researchers at Stanford and the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), have devised a new method to harvest more information from the genomes of archaic humans to potentially reveal the physical consequences of genomic differences between us and them.

Their work, published April 22 in eLife, focused on sequences related to gene expression - the process by which genes are activated or silenced, which determines when, how and where DNA's instructions are followed. Gene expression tends to be the genetic detail that determines physical differences between closely related groups.

Starting with 14,042 genetic variants unique to modern humans, the researchers found 407 that specifically contribute to differences in gene expression between modern and archaic humans. In further analysis, they determined that the differences were more likely to be associated with the vocal tract and the cerebellum, which is the part of our brain that receives sensory information and controls voluntary movement, including walking, coordination, balance and speech.

"It just seems so implausible that you could make a call like, 'I think the voice box evolved,' from the information we have," said Dmitri Petrov, the Michelle and Kevin Douglas Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences, who is co-senior author of the paper with Gokhman and Nadav Ahituv, a professor of bioengineering at UCSF. "The predictions are almost science fiction. If five years ago, somebody told me that this would be possible, I would not have put much money on it."

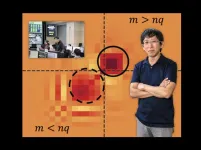

The path to modern humans

With such a large number of variants to examine, the researchers relied on a technique called a "massively parallel reporter assay" to test which sequences actually affect gene regulation. Their version of this technique, which was developed by Ahituv, involves packaging the DNA sequence variant into a "reporter gene" inside a virus. That virus is then put into a cell. If that variant affects gene expression, the reporter gene produces a barcoded molecule that identifies what DNA sequence it came from. The barcode allows the researchers to scan the products of a large number of variants at once.

Essentially, the whole process imitates an abridged version of how each variant would play out in a cell in real life and reports the results.

Lana Harshman, a graduate student at UCSF and co-lead author of the paper, infected three types of cells with the team's variant packages. These cells were related to the brain, skeleton and early development - subjects that are most likely to reveal evolutionary differences between us and our most recent ancestors. Carly Weiss, a postdoctoral scholar in the Petrov lab and co-lead author of the paper, analyzed the results of these experiments.

In total, the researchers found 407 sequences that represented a change in expression in modern humans compared to our predecessors. Among that list, genes that affect the cerebellum and genes that affect the voice box, pharynx, larynx and vocal cords seem to be overrepresented.

"This would suggest some kind of rapid evolution of those organs or some kind of a path that is specific to modern humans," said Gokhman. The next step, he added, would be trying to understand more about these sequences and the roles they played in the evolution of modern humans.

Even with those unknowns, this technique by itself is a significant advance for evolutionary research, said Petrov.

"This goes beyond the sequencing of the DNA from the Neanderthal and Denisovan bones. This begins to put meaning on those differences," said Petrov. "It's an important conceptual step from just the sequence - no tissue, no cells - to biological information and will enable many future studies."

INFORMATION:

Hunter Fraser, associate professor of biology at Stanford, and Fumitaka Inoue (UCSF) are also co-authors of the paper. Fraser is also a member of Stanford Bio-X, the Maternal & Child Health Research Institute (MCHRI) and the Stanford Cancer Institute. Petrov is also a member of Stanford Bio-X and the Maternal & Child Health Research Institute (MCHRI), and an affiliate of the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

This research was funded by Human Frontier, Rothschild and Zuckerman fellowships; the National Human Genome Research Institute; the National Institute of Mental Health; the Uehara Memorial Foundation; and the Stanford Center for Computational, Evolutionary and Human Genomics (CEHG).

Gossip is often considered socially taboo and dismissed for its negative tone, but a Dartmouth study illustrates some of its merits. Gossip facilitates social connection and enables learning about the world indirectly through other people's experiences.

Gossip is not necessarily spreading rumors or saying bad things about other people but can include small talk in-person or online, such as having a private chat during a Zoom meeting. Prior research has found that approximately 14% of people's daily conversations are gossip, and primarily neutral in tone.

"Gossip is ...

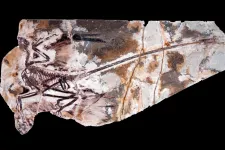

Powered flight in animals -that uses flapping wings to generate thrust- is a very energetically demanding mode of locomotion that requires many anatomical and physiological adaptations. In fact, the capability to develop it has only appeared four times in the evolutionary history of animals: on insects, pterosaurs, birds and bats.

A research paper published in 2020 in the scientific journal Current Biology concluded that, apart from birds -the only living descendants of dinosaurs-, powered flight would have originated independently in other three groups of dinosaurs. A conclusion that makes a great impact, as it increases the number of vertebrates that would have developed this costly mode of locomotion, ...

A major hurdle to developing new and effective treatments for drug addiction is better understanding how exactly it manifests itself before, during and after chronic use. In a paper published online in the April 21, 2021 issue of the journal eNeuro, an international team of researchers led by scientists at University of California San Diego School of Medicine describe the creation of two unique collections of more than 20,000 biological samples collected from laboratory rats before, during and after chronic use of cocaine and oxycodone.

Developed by the Preclinical Addiction Research Consortium, located in the Department of Psychiatry at UC San Diego School of Medicine and at Skaggs School of Pharmacy ...

Corn is America's top agricultural crop, and also one of its most wasteful. About half the harvest--stalks, leaves, husks, and cobs-- remains as waste after the kernels have been stripped from the cobs. These leftovers, known as corn stover, have few commercial or industrial uses aside from burning. A new paper by engineers at UC Riverside describes an energy-efficient way to put corn stover back into the economy by transforming it into activated carbon for use in water treatment.

Activated carbon, also called activated charcoal, is charred biological material that has been treated to create millions of microscopic pores that increase how much the material can absorb. It has many industrial ...

How often have you laid in bed scrolling through news stories, social media or responding to a text? After staring at the screen, have you ever found that it is harder to fall asleep?

It's widely believed that the emitted blue light from phones disrupts melatonin secretion and sleep cycles. To reduce this blue light emission and the strain on eyes, Apple introduced an iOS feature called Night Shift in 2016; a feature that adjusts the screen's colors to warmer hues after sunset. Android phones soon followed with a similar option, and now most smartphones have some sort of night mode function that claims ...

The process designed to harvest on Earth the fusion energy that powers the sun and stars can sometimes be tricked. Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics laboratory have derived and demonstrated a bit of slight-of-hand called "quasi-symmetry" that could accelerate the development of fusion energy as a safe, clean and virtually limitless source of power for generating electricity.

Fusion reactions combine light elements in the form of plasma -- the hot, charged state of matter composed of free electrons and atomic nuclei that makes up 99 percent of the visible universe ...

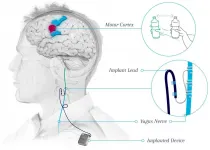

LOS ANGELES -- Every year, more than 795,000 people in the United States have a stroke. Of these, approximately 80% lose arm function and as many as 50-60% of this population still experience problems six months later.

Traditionally, stroke patients try to regain motor function through physical rehabilitation, where patients re-learn pre-stroke skills, such as eating motions and grasping. However, most patients eventually plateau and stop improving over time.

Now, results of a clinical trial published in The Lancet gives patients new hope in their recovery.

Patients who received a novel treatment that combines vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) and rehabilitation showed ...

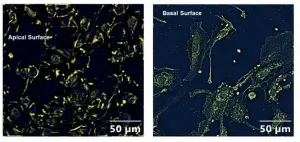

A new study performed in human lung airway cells is one of the first to show a potential link between exposure to organophosphate pesticides and increased susceptibility to COVID-19 infection. The findings could have implications for veterans, many of whom were exposed to organophosphate pesticides during wartime.

Exposure to organophosphate pesticides is thought to be one of the possible causes of Gulf War Illness, a cluster of medically unexplained chronic symptoms that can include fatigue, headaches, joint pain, indigestion, insomnia, dizziness, respiratory disorders and memory problems. More than 25% of Gulf War veterans are estimated to experience this condition.

"We have identified a basic mechanism linked with inflammation that could increase susceptibility to COVID-19 infection ...

During infection, SARS-CoV-2 binds to a cellular receptor known as angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) before entering a cell and replicating. Because it is not well established whether common blood pressure medications can increase the levels of ACE2, there has been some concern that patients taking these medications might be more susceptible to COVID-19.

In a new study, researchers led by Hans Ackerman, MD, DPhil, in the Laboratory of Malaria and Vector Research (LMVR) at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, found that mice treated with an ACE inhibitor blood pressure medication showed increased levels of ACE2. However, mice that received both an ACE inhibitor and a different blood pressure medicine known as an angiotensin ...

Tyrannosaurus rex dinosaurs chomped through bone by keeping a joint in their lower jaw steady like an alligator, rather than flexible like a snake, according to a study being presented at the END ...