"Now, we are able to access these patients' gene mutations using CRISPR-Cas9 technology," explains Professor Simone Spuler, head of the Myology Lab at the Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), a joint institution of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association and Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin. "We care for more than 2,000 patients at the Charité outpatient clinic for muscle disorders, and quickly recognized the potential of the new technology." The researchers immediately started working with some of the affected families, and have now presented their results in the journal JCI Insight. In the families studied, the parents were healthy and had no idea they possessed a mutated gene. The children all inherited a copy of the disease mutation from both parents.

Edited human muscle stem cells developed into muscle fibers in mice

The term "muscular dystrophy" is used to refer to some 50 different diseases. "They all take the same course, but differ due to the mutation of different genes," explains Spuler. "And even within the genes, different sites can be mutated." Following a genomic analysis of all patients, the researchers chose one family because of their particular form of the disease: Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 2D/R3 is relatively common, progresses rapidly, and has a suitable docking site for the "genetic scissors" close to the mutation on the DNA.

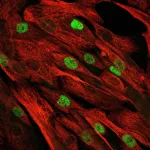

For the study, the researchers took a sample of muscle tissue from a ten-year-old patient, isolated the stem cells, multiplied these in vitro, and used base editing to replace a base pair at the mutated site. They then injected the edited muscle stem cells into mouse muscles, which can tolerate foreign human cells. These multiplied in the rodent and most developed into muscle fibers. "With this, we were able to show for the first time that it is possible to replace diseased muscle cells with healthy ones," says Spuler. Following further tests, the repaired stem cells will be reintroduced to the patient.

Base editing - a sophisticated technique

Base editing is a newer and highly sophisticated variant of the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing tool. Whereas in the "classic" method, both strands of DNA are cut by these molecular scissors, the Cas enzymes used for base editing merely snip off the residual glucose from a particular base and attach a different one, thus creating a different base at the targeted site. "This tool works more like tweezers than scissors, and is perfect for carrying out targeted point mutations in a gene," says Dr. Helena Escobar, a molecular biologist in Spuler's team. "It is also a much safer method, because unwanted changes are extremely rare. In the genetically repaired muscle stem cells, we have not witnessed any misediting at unintended regions of the genome." Escobar is the study's lead author and the one who developed the technique for the muscle cells.

Autologous cell therapy - which involves removing a patient's own stem cells, editing them outside the body and then injecting them back into the muscle - will not enable sufferers who are already wheelchair-bound to walk again. "We cannot repair muscle that has already atrophied and been replaced by connective tissue," Spuler stresses. And the number of cells that can be edited in vitro is also limited. However, the study provides the first proof that a form of therapy may even be possible for a group of previously incurable diseases, and it could be used to repair small muscle defects, such as those in the finger flexor.

One step closer to a cure

But this is just the first step. "The next milestone will be to find a way to inject the base editor directly into the patient. Once inside the body, it would 'swim' around for a short while, edit all the muscle stem cells, and then quickly break down again." The team wants to start the first trials in a mouse model soon. If this also works, newborns could be tested for corresponding gene mutations in the future and the curative therapy could be initiated at a time when comparatively few cells would need to be edited.

So, what might an in vivo therapy for muscular dystrophy look like in concrete terms? This is something that scientists have been testing on animal models for some time using viral vectors. However, Helena Escobar explains that because these vectors remain in the body for too long, the risk of misediting and toxic effects is too high. "An alternative would be for mRNA molecules that contain the information for the editor to synthesize the tools in vivo," says the molecular biologist. "mRNA breaks down very quickly in the body, so the therapeutic enzymes can only remain in an active state for a short time." The therapy could probably also be repeated, if necessary. "We do not yet know whether this would need to be a therapy cycle involving several applications."

This therapeutic avenue would mean that, unlike with autologous cell therapy, not every patient would need to be treated individually. For each form of muscle therapy, one "tool" would be sufficient to cure muscle atrophy before major damage even occurred. But, for now, that is still a long way off.

INFORMATION:

Scientific contacts

Prof. Simone Spuler

Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC)

Myology Lab

+49 30 4505-40501

simone.spuler@charite.de or simone.spuler@mdc-berlin.de

Dr. Helena Escobar

Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC)

Myology Lab

+49 30 4505-540526

helena.escobar@charite.de or Helena.escobar@mdc-berlin.de

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC)

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) was founded in Berlin in 1992. It is named for the German-American physicist Max Delbrück, who was awarded the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine. The MDC's mission is to study molecular mechanisms in order to understand the origins of disease and thus be able to diagnose, prevent and fight it better and more effectively. In these efforts the MDC cooperates with the Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH ) as well as with national partners such as the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and numerous international research institutions. More than 1,600 staff and guests from nearly 60 countries work at the MDC, just under 1,300 of them in scientific research. The MDC is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (90 percent) and the State of Berlin (10 percent), and is a member of the Helmholtz Association of German Research Centers. http://www.mdc-berlin.de

The Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC)

The Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC) is an institutional cooperation and a joint research structure of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) and the Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, founded in 2007. The aim of the ECRC is to expand and strengthen interdisciplinary activities between basic and clinical researchers and to shorten the pathway from discovery to clinical application. The ECRC is situated at the science campus in Berlin-Buch and provides unique conditions for patient-oriented research and clinical studies in a research-driven environment.