(Press-News.org) As the health of ecosystems in regions around the globe declines due to a variety of rising threats, scientists continue to seek clues to help prevent future collapses.

A new analysis by scientists from around the world, led by a researcher at the University of California San Diego, is furthering science's understanding of species interactions and how diversity contributes to the preservation of ecosystem health.

A coalition of 49 researchers examined a deep well of data describing tree species in forests located across a broad range of countries, ecosystems and latitudes. Information about the 16 forest diversity plots in Panama, China, Sri Lanka, Puerto Rico and other locations--many in remote, inaccessible areas--had been collected by hundreds of scientists and students over decades.

Lead researcher Christopher Wills, an evolutionary biologist and professor emeritus in the UC San Diego Division of Biological Sciences, says the new study addresses large questions about these complex ecosystems--made up of trees, animals, insects and even bacteria and viruses--and how such stunning diversity is maintained to support the health of the forest.

The new analysis, believed to be the most detailed study of such an enormous set of ecological data, is published in the journal PLOS Computational Biology.

"Observational and experimental evidence shows that all ecosystems are characterized by strong interactions between and among their many species. These webs of interactions can be important contributors to the preservation of ecosystem diversity," said Wills.

The authors note, however, that many of these interactions--including those involving microscopic pathogens and the chemical defenses mounted by their prey--are not easy to identify and analyze in ecosystems that feature tens to hundreds of millions of inhabitants.

The researchers employed a detailed computational tool to extract hidden details from the forest census data. Their new "equal-area-annulus" method identifies pairs and groups of tree species that show unusually high or low levels of between-species interactions affecting their recruitment, mortality and growth. The authors found, unexpectedly, that closely-related pairs of tree species in a forest often interact weakly with each other, while distantly-related pairs can often interact with surprising strength. Such new information enables the design of further fieldwork and experiments to identify the many other species of organisms that have the potential to influence these interactions. These studies will in turn pave a path to understanding the roles of these webs of interactions in ecosystem stability.

Most of the thousands of significant interactions that the new analysis revealed were of types that give advantages to the tree species if they are rare. The advantages disappear, however, when those species become common. Some well-studied examples of such disappearing advantages involve diseases of certain species of tree. These specialized diseases are less likely to spread when their host trees are rare, and more likely to spread when the hosts are plentiful. Such interaction patterns can help to maintain many different host tree species simultaneously in an ecosystem.

"We explored how our method can be used to identify the between-species interactions that play the largest roles in the maintenance of ecosystems and their diversity," said Wills. "The interplay we have found between and among species helps to explain how the numerous species in these complex ecosystems can buffer the ecosystems against environmental changes, enabling the ecosystems themselves to survive."

Moving forward, the scientists plan to continue using the data to help tease out specific influences that are essential to ecosystem health.

"We want to show how we can maintain the diversity of the planet at the same time as we are preserving ecosystems that will aid our own survival," said Wills.

INFORMATION:

The full coauthor list includes: Christopher Wills, Bin Wang, Shuai Fang, Yunquan Wang, Yi Jin, James Lutz, Jill Thompson, Kyle Harms, Sandeep Pulla, Bonifacio Pasion, Sara Germain, Heming Liu, Joseph Smokey, Sheng-Hsin Su, Nathalie Butt, Chengjin Chu, George Chuyong, Chia-Hao Chang-Yang, H. S. Dattaraja, Stuart Davies, Sisira Ediriweera, Shameema Esufali, Christine Dawn Fletcher, Nimal Gunatilleke, Savi Gunatilleke, Chang-Fu Hsieh, Fangliang He, Stephen Hubbell, Zhanqing Hao, Akira Itoh, David Kenfack, Buhang Li, Xiankun Li, Keping Ma, Michael Morecroft, Xiangcheng Mi, Yadvinder Malhi, Perry Ong, Lillian Jennifer Rodriguez, H. S. Suresh, I Fang Sun, Raman Sukumar, Sylvester Tan, Duncan Thomas, Maria Uriarte, Xihua Wang, Xugao Wang, T.L. Yao, Jess Zimmermann.

Jeremy Edwards, director of the Computational Genomics and Technology (CGaT) Laboratory at The University of New Mexico, and his colleagues at Centrillion Technologies in Palo Alto, Calif. and West Virginia University, have developed a chip that provides a simpler and more rapid method of genome sequencing for viruses like COVID-19.

Their research, titled, "Highly Accurate Chip-Based Resequencing of SARS-CoV-2 Clinical Samples" was published recently in the American Chemical Society's Langmuir. As part of the research, scientists created a tiled genome array they developed for rapid and inexpensive full viral genome resequencing and applied their SARS-CoV-2-specific genome tiling array to rapidly and accurately resequenced ...

Boston, MA (April 30, 2021) - A new study, presented today at the AATS 101st Annual Meeting, shows that non-invasive cell-free DNA tests can reduce the need for regular surveillance biopsies to detect early rejection in heart transplant patients. The study was the first of its kind to be performed on both adult and pediatric patients.

Pediatric and adult heart transplant recipients were recruited prospectively from eight participating sites and followed longitudinally for at least 12 months with serial plasma samples collected immediately prior to all endomyocardial biopsies. Structured biopsy results and clinical data were collected and monitored by an independent clinical research organization (CRO).

For ...

Boston, MA (April 30, 2021) - A new study, presented today at the AATS 101st Annual Meeting, found that severely ill COVID-19 patients treated with ECMO did not suffer worse long-term outcomes than other mechanically-ventilated patients. The multidisciplinary team included cardio thoracic surgeons, critical care doctors, medical staff at long-term care facilities, physical therapists and other specialists, and followed patients at five academic centers: University of Colorado; University of Virginia; University of Kentucky; Johns Hopkins University; and Vanderbilt University. ...

LA JOLLA--(April 30, 2021) Scientists have known for a while that SARS-CoV-2's distinctive "spike" proteins help the virus infect its host by latching on to healthy cells. Now, a major new study shows that they also play a key role in the disease itself.

The paper, published on April 30, 2021, in Circulation Research, also shows conclusively that COVID-19 is a vascular disease, demonstrating exactly how the SARS-CoV-2 virus damages and attacks the vascular system on a cellular level. The findings help explain COVID-19's wide variety of seemingly unconnected complications, and could ...

While the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing system has become the poster child for innovation in synthetic biology, it has some major limitations. CRISPR-Cas9 can be programmed to find and cut specific pieces of DNA, but editing the DNA to create desired mutations requires tricking the cell into using a new piece of DNA to repair the break. This bait-and-switch can be complicated to orchestrate, and can even be toxic to cells because Cas9 often cuts unintended, off-target sites as well.

Alternative gene editing techniques called recombineering instead perform this bait-and-switch ...

Medical researchers at Flinders University have established a new link between high body mass index (BMI) and breast cancer survival rates - with clinical data revealing worse outcomes for early breast cancer (EBC) patients and improved survival rates in advanced breast cancer (ABC).

In a new study published in a top breast cancer journal- researchers evaluated data from 5 thousand patients with EBC and 3496 with ABC to determine associations between BMI and survival rates across both stages.

Researchers say the results present an 'obesity paradox' which will impact the survival outcomes of the 19,807 women and 167 men diagnosed with breast cancer in Australia in 2020.

Natansh Modi, a NHMRC PHD Candidate at Flinders University, says understanding the ...

The Brazilian Amazon rainforest released more carbon than it stored over the last decade - with degradation a bigger cause than deforestation - according to new research.

More than 60% of the Amazon rainforest is in Brazil, and the new study used satellite monitoring to measure carbon storage from 2010-2019.

The study found that degradation (parts of the forest being damaged but not destroyed) accounted for three times more carbon loss than deforestation.

The research team - including INRAE, the University of Oklahoma and the University of Exeter - said large areas of rainforest were degraded or destroyed due to human activity and climate change, leading to carbon loss.

The findings, published in Nature Climate Change, also ...

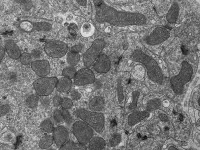

Mitochondria are the energy suppliers of our body cells. These tiny cell components have their own genetic material, which triggers an inflammatory response when released into the interior of the cell. The reasons for the release are not yet known, but some cardiac and neurodegenerative diseases as well as the ageing process are linked to the mitochondrial genome. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Biology of Ageing and the CECAD Cluster of Excellence in Ageing research have investigated the reasons for the release of mitochondrial genetic material and found a direct link to cellular metabolism: when the cell's DNA building blocks are in short supply, mitochondria release their genetic material and trigger inflammation. ...

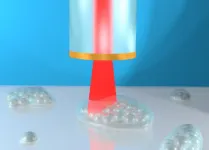

Scientists at the University of Nottingham have developed an ultrasonic imaging system, which can be deployed on the tip of a hair-thin optical fibre, and will be insertable into the human body to visualise cell abnormalities in 3D.

The new technology produces microscopic and nanoscopic resolution images that will one day help clinicians to examine cells inhabiting hard-to-reach parts of the body, such as the gastrointestinal tract, and offer more effective diagnoses for diseases ranging from gastric cancer to bacterial meningitis.

The high level of performance the technology delivers is currently only possible in state-of-the-art research labs with large, scientific instruments - whereas this compact system has the potential to bring it into clinical settings to improve patient care.

The ...

Successful navigation requires the ability to separate memories in a context-dependent manner. For example, to find lost keys, one must first remember whether the keys were left in the kitchen or the office. How does the human brain retrieve the contextual memories that drive behavior? J.B. Julian of the Princeton Neuroscience Institute at Princeton University, USA, and Christian F. Doeller of the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany, found in a recent study that modulation of map-like representations in our brain's hippocampal formation can predict contextual memory retrieval in an ambiguous environment.

The researchers developed a novel virtual reality navigation task in which human participants learned object positions in two different ...