INFORMATION:

'Last resort' antibiotic pops bacteria like balloons

Scientists have revealed how an antibiotic of 'last resort' kills bacteria.

2021-05-04

(Press-News.org) Scientists have revealed how an antibiotic of 'last resort' kills bacteria.

The findings, from Imperial College London and the University of Texas, may also reveal a potential way to make the antibiotic more powerful.

The antibiotic colistin has become a last resort treatment for infections caused by some of the world's nastiest superbugs. However, despite being discovered over 70 years ago, the process by which this antibiotic kills bacteria has, until now, been something of a mystery.

Now, researchers have revealed that colistin punches holes in bacteria, causing them to pop like balloons. The work, funded by the Medical Research Council and Wellcome Trust, and published in the journal eLife, also identified a way of making the antibiotic more effective at killing bacteria.

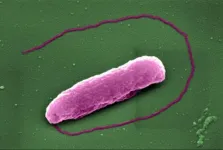

Colistin was first described in 1947, and is one of the very few antibiotics that is active against many of the most deadly superbugs, including E. coli, which causes potentially lethal infections of the bloodstream, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii, which frequently infect the lungs of people receiving mechanical ventilation in intensive care units.

These superbugs have two 'skins', called membranes. Colistin punctures both membranes, killing the bacteria. However, whilst it was known that colistin damaged the outer membrane by targeting a chemical called lipopolysaccharide (LPS), it was unclear how the inner membrane was pierced.

Now, a team led by Dr Andrew Edwards from Imperial's Department of Infectious Disease, has shown that colistin also targets LPS in the inner membrane, even though there's very little of it present.

Dr Edwards said: "It sounds obvious that colistin would damage both membranes in the same way, but it was always assumed colistin damaged the two membranes in different ways. There's so little LPS in the inner membrane that it just didn't seem possible, and we were very sceptical at first. However, by changing the amount of LPS in the inner membrane in the laboratory, and also by chemically modifying it, we were able to show that colistin really does puncture both bacterial skins in the same way - and that this kills the superbug. "

Next, the team decided to see if they could use this new information to find ways of making colistin more effective at killing bacteria.

They focussed on a bacterium called Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which also causes serious lung infections in people with cystic fibrosis. They found that a new experimental antibiotic, called murepavadin, caused a build up of LPS in the bacterium's inner skin, making it much easier for colistin to puncture it and kill the bacteria.

The team say that as murepavadin is an experimental antibiotic, it can't be used routinely in patients yet, but clinical trials are due to begin shortly. If these trials are successful, it may be possible to combine murepavadin with colistin to make a potent treatment for a vast range of bacterial infections.

Akshay Sabnis, lead author of the work also from the Department of Infectious Disease, said: "As the global crisis of antibiotic resistance continues to accelerate, colistin is becoming more and more important as the very last option to save the lives of patients infected with superbugs. By revealing how this old antibiotic works, we could come up with new ways to make it kill bacteria even more effectively, boosting our arsenal of weapons against the world's superbugs."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

One cup of leafy green vegetables a day lowers risk of heart disease

2021-05-04

New Edith Cowan University (ECU) research has found that by eating just one cup of nitrate-rich vegetables each day people can significantly reduce their risk of heart disease.

The study investigated whether people who regularly ate higher quantities of nitrate-rich vegetables, such as leafy greens and beetroot, had lower blood pressure, and it also examined whether these same people were less likely to be diagnosed with heart disease many years later.

Cardiovascular diseases are the number one cause of death globally, taking around 17.9 million lives each year.

Researchers examined data from over 50,000 people residing in Denmark taking part in the Danish Diet, ...

Microplastics found in Europe's largest ice cap

2021-05-04

In a recent article in Sustainability, scientists from Reykjavik University (RU), the University of Gothenburg, and the Icelandic Meteorological Office describe their finding of microplastic in a remote and pristine area of Vatnajokull glacier in Iceland, Europe's largest ice cap. Microplastics may affect the melting and rheological behaviour of glaciers, thus influencing the future meltwater contribution to the oceans and rising sea levels.

This is the first time that the finding of microplastic in the Vatnajökull glacier is described. The group visualised and identified microplastic particles of various sizes and materials by optical microscopy and μ-Raman spectroscopy.

The discussion about microplastics has mainly been focused on the contamination ...

Climate action potential in waste incineration plants

2021-05-04

Over the coming decades, our economy and society will need to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions as called for in the Paris Agreement. But even a future low-carbon economy will emit some greenhouse gases, such as in the manufacture of cement, steel, in livestock and crop farming, and in the chemical and pharmaceutical industries. To meet climate targets, these emissions need to be offset. Doing so requires "negative emissions" technologies, by means of which CO2 is removed from the atmosphere and permanently stored in underground repositories.

Researchers at ETH Zurich have now calculated the potential of one of these technologies for Europe: the combination of energy extraction from biomass with the capture and ...

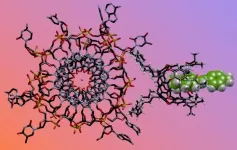

Chemical 'nose' sniffs critical differences in DNA structures

2021-05-04

Small changes in the structure of DNA have been implicated in breast cancer and other diseases, but they've been extremely difficult to detect -- until now.

Using what they describe as a "chemical nose," UC Riverside chemists are able to "smell" when bits of DNA are folded in unusual ways. Their work designing and demonstrating this system has been published in the journal Nature Chemistry.

"If a DNA sequence is folded, it could prevent the transcription of a gene linked to that particular piece of DNA," said study author and UCR chemistry professor Wenwan Zhong. "In other words, this could have a positive effect by silencing a gene with the potential to cause cancer or promote tumors."

Conversely, DNA folding ...

How a bad day at work led to better COVID predictions

2021-05-04

Talking about your bad day at work could lead to great solutions. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Associate Professor Saket Navlakha and his wife, Dr. Sejal Morjaria, an infectious disease physician at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK), found a way to predict COVID-19 severity in cancer patients. The computational tool they developed prevents unnecessary expensive testing and improves patient care.

Morjaria says, "Generally, I have good intuition for how patients will progress." However, that intuition failed her when confronted with COVID-19. She says:

"When the pandemic ...

Increased use of minimally invasive non-endoscopic tests for Barrett's esophagus screening

2021-05-04

Below please find summaries of new articles that will be published in the next issue of Annals of Internal Medicine. The summaries are not intended to substitute for the full articles as a source of information. This information is under strict embargo and by taking it into possession, media representatives are committing to the terms of the embargo not only on their own behalf, but also on behalf of the organization they represent.

1. Increased use of minimally invasive non-endoscopic tests for Barrett's esophagus screening could impact detection and prevention of esophageal cancer

Abstract: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M20-7164

URL ...

Solar development: super bloom or super bust for desert species?

2021-05-04

Throughout the history of the West, human actions have often rushed the desert -- and their actions backfired. In the 1920s, the Colorado River Compact notoriously overallocated water still used today by several western states because water measurements were taken during a wet period.

More currently, operators of the massive Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System in the Mojave Desert are spending around $45 million on desert tortoise mitigation after initial numbers of the endangered animals were undercounted before its construction.

A study published in the journal Ecological Applications from the University of California, Davis, and UC Santa Cruz warns against another potential desert timing mismatch amid the race against climate change and toward rapid renewable ...

Revealing the secret cocoa pollinators

2021-05-04

The importance of pollinators to ensure successful harvests and thus global food security is widely acknowledged. However, the specific pollinators for even major crops - such as cocoa - haven't yet been identified and there remain many questions about sustainability, conservation and plantation management to enhance their populations and, thereby, pollination services. Now an international research team based in Central Sulawesi, Indonesia and led by the University of Göttingen has found that in fact ants and flies - but not ceratopogonid midges as was previously thought - appear to have a crucial role to play. In addition, they found ...

Development of microsatellite markers for censusing of endangered rhinoceros

2021-05-04

Today, the Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) is critically endangered, with fewer than 100 individuals surviving in Indonesia on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo. To ensure survival of the threatened species, accurate censusing is necessary to determine the genetic diversity of remaining populations for conservation and management plans.

A new study reported in BMC Research Notes characterized 29 novel polymorphic microsatellite markers -- repetitive DNA sequences -- that serve as a reliable censusing method for wild Sumatran rhinos. The study was a collaborative effort involving the University ...

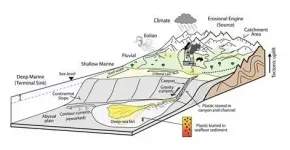

Plastic pollution in the deep sea: A geological perspective

2021-05-04

Boulder, Colo., USA: A new focus article in the May issue of Geology summarizes research on plastic waste in marine and sedimentary environments. Authors I.A. Kane of the Univ. of Manchester and A. Fildani of the Deep Time Institute write that "Environmental pollution caused by uncontrolled human activity is occurring on a vast and unprecedented scale around the globe. Of the diverse forms of anthropogenic pollution, the release of plastic into nature, and particularly the oceans, is one of the most recent and visible effects."

The authors cite multiple studies, including one in the May issue by Guangfa Zhong and Xiaotong ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

[Press-News.org] 'Last resort' antibiotic pops bacteria like balloonsScientists have revealed how an antibiotic of 'last resort' kills bacteria.