(Press-News.org) BAR HARBOR, MAINE — Our kidneys are charged with the extraordinary task of filtering about 53 gallons of fluid a day, a process that depends on podocytes, tiny, highly specialized cells in the cluster of blood vessels in the kidney where waste is filtered that are highly vulnerable to damage.

In research at the MDI Biological Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine, a team led by Iain Drummond, Ph.D., director of the Kathryn W. Davis Center for Regenerative Biology and Aging, has identified the signaling mechanisms underlying podocyte formation, or morphogenesis. The discovery opens the door to the development of therapies to stimulate the regeneration of these cells, which are vital to ridding the body of toxins.

"Podocytes play a very important role in kidney function," said Hermann Haller, M.D., president of the MDI Biological Laboratory and a nephrologist who leads the department of nephrology and hypertension at Hannover Medical School in Hanover, Germany. "The discovery of the signaling underlying podocyte morphogenesis by a team led by Iain Drummond is a major stride forward in the treatment of kidney disease."

The study, entitled "Autonomous Calcium Signaling in Human and Zebrafish Podocytes Controls Kidney Filtration Barrier Morphogenesis," was recently published in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

In addition to Drummond, authors include Melissa Little, Ph.D., Aude Dorison, Ph.D., Irene Ghobrial and Alejandro Hidalgo-Gonzalez, Ph.D., all of The Royal Children's Hospital, Murdoch Children's Research Institute in Melbourne, Australia; Heiko Schenk, M.D., and Jan Hegermann of Hannover Medical School, Hanover, Germany; and Lynne Staggs of Hannover Medical School and the MDI Biological Laboratory.

The discovery of the signaling mechanism underlying podocyte formation is relevant to the treatment of a range of kidney conditions that can damage the glomerular filtration barrier, including acute kidney injury, developmental defects, premature birth defects, kidney cancer, polycystic kidney disease and chronic kidney disease (CDK) caused by diabetes or hypertension.

A major public health threat

In recent years, CDK has emerged as a major public health threat, especially among those age 60 and over, due to diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease, all of which can contribute to kidney damage and all of which are increasing due to the aging of the world's population. Approximately 38 million Americans, or 15 percent of the adult population, is estimated to have kidney disease.

When kidneys fail, the usual treatment is dialysis, an expensive, time-consuming procedure in which the blood is cleansed by an external filtering device. Though transplantation is another option, only a fraction of the tens of thousands of end-stage renal disease patients waiting for a kidney transplant receive one because the number of organ donors is insufficient to meet demand.

As a result of the limited options, kidney research at the MDI Biological Laboratory has focused on the regeneration of kidney tissue, and especially of nephrons, the functional units of the kidney, which include the glomerulus, in which the work of filtering the blood takes place. The approximately 1 million glomeruli in the body filter excess fluid and waste products from the blood, preventing the build-up of toxic waste.

The membrane of the glomerulus is lined with podocytes, whose interdigitated, foot-like projections (podo is Latin for "having a foot") extend into the glomerular space. The podocytes are connected by a thin, mesh-like web called a "slit diaphragm" that functions as the final filtration barrier before fluid enters the glomerular space, from which it passes into collecting tubules and is ultimately excreted as urine.

"Podocytes are complex, which increases their vulnerability to injury," Drummond explained. "There are many moving parts that have to come together just right in order to create the filtration barrier, and defects in any one of these can lead to disease. The more we know about how the individual parts and processes work together, the more targets we have for potential therapeutic interventions."

In in vivo studies in zebrafish embryos and in vitro studies in maturing human kidney organoids, which are stem cell-derived "organs in a dish," Drummond and his colleagues have discovered that calcium signaling is required for the formation of the podocyte foot process and slit diaphragm. The discovery supports the critical role of calcium signaling in the formation of the filtration barrier.

The discovery was enabled by a genetically encoded, green fluorescent calcium biosensor, GCaMP, that can be targeted to specific cell types. Because it lights up when calcium signaling is active, the biosensor allows scientists to image calcium signaling in the podocytes of transparent zebrafish embryos in real time under a fluorescence microscope to determine how they are made and what goes wrong during disease.

The zebrafish as a model for human disease

An important outcome of Drummond's research is the establishment of the zebrafish as a model for human glomerular development and disease. The functional equivalency of podocytes in zebrafish and in human organoids suggests that their role has been conserved through evolution, thus validating the relevance of the zebrafish as a vertebrate model and as a screening platform for new therapies.

The research also identifies new routes for promoting kidney regeneration in humans. Unlike humans, zebrafish regenerate glomeruli throughout their adult lives. Though it is unknown if the signaling mechanisms employed during development are recapitulated during regeneration, Drummond thinks this is likely, in which case a deeper understanding could lead to therapies to trigger regeneration in humans.

"We wanted to go beyond looking at the shape and size and movement of cells during the process of forming the filter to the signals they are passing to generate this complex filter architecture," Drummond said. "Once we understand these signals, we can accelerate tissue formation by promoting productive regenerative communication though our own messages in the form of signaling molecules."

In recent years, the MDI Biological Laboratory has become a hub for kidney regeneration research due to its participation in a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded consortium, (Re)Building a Kidney (RBK), the aim of which is to develop a biological artificial kidney. The discovery of the signaling mechanism underlying podocyte formation will play a critical role in generating replacement kidney tissue.

In making his discovery, Drummond is building on the MDI Biological Laboratory's distinguished historical reputation in kidney physiology. Much of what is known today about human kidney function was discovered at the MDI Biological Laboratory in the 20th century through comparative biological studies.

INFORMATION:

Drummond's research is supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the NIH (grant numbers R01DK053093, UH3DK107372, R01DK071041 and UC2DK126021).

About the MDI Biological Laboratory

We aim to improve human health and healthspan by uncovering basic mechanisms of tissue repair, aging and regeneration, translating our discoveries for the benefit of society and developing the next generation of scientific leaders. For more information, please visit mdibl.org.

A team of University of Alberta researchers has discovered a way to use 3-D bioprinting technology to create custom-shaped cartilage for use in surgical procedures. The work aims to make it easier for surgeons to safely restore the features of skin cancer patients living with nasal cartilage defects after surgery.

The researchers used a specially designed hydrogel--a material similar to Jell-O--that could be mixed with cells harvested from a patient and then printed in a specific shape captured through 3-D imaging. Over a matter of weeks, the material is cultured in a lab to become functional cartilage.

"It takes a lifetime to make cartilage in an individual, while this method takes about four weeks. So you still expect ...

Metallacages prepared via coordination-driven self-assembly have received extensive attention because of their three-dimensional layout and cavity-cored nature. The construction of light-emitting materials employing metallacages as a platform has also gained significant interest due to their good modularity in photophysical properties, which bring emerging applications in fields as diverse as sensing, biomedicine, and catalysis.

However, the luminescence efficiency of conventional luminophores significantly decreases in the aggregate state because they encounter unfavorable aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ). Therefore, it was quite a challenge to fabricate light-emitting metallacages with high luminescence efficiency in various physical states.

In 2001, Tang's group ...

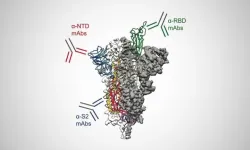

The most complete picture yet is coming into focus of how antibodies produced in people who effectively fight off SARS-CoV-2 work to neutralize the part of the virus responsible for causing infection. In the journal Science, researchers at The University of Texas at Austin describe the finding, which represents good news for designing the next generation of vaccines to protect against variants of the virus or future emerging coronaviruses.

Previous research focused on one group of antibodies that target the most obvious part of the coronavirus's spike protein, called the receptor-binding domain (RBD). Because the RBD is the part of the spike that attaches directly to human cells and enables the virus to infect them, ...

New York, NY (May 4, 2021) - A powerful, long-term study from WCS adds scientific backing for global calls for conserving 30 percent of the world's ocean. The studied no-take marine protected areas (MPAs) increased the growth of fish populations by 42 percent when fishing was unsustainable in surrounding areas, achieving the benefits of stable and high production of fish populations for fishers, while protecting threatened ecosystems.

The study recorded fish catches for 24-years across a dozen fish landing sites within two counties in Kenya, which allowed scientists to evaluate the long-term impacts of two different fisheries management methods. While one county ...

Harsh prison sentences for juvenile crimes do not reduce the probability of conviction for violent crimes as an adult, and actually increase the propensity for conviction of drug-related crimes, finds a new study by economists at UC Riverside and the University of Louisiana. Harsh juvenile sentences do reduce the likelihood of conviction for property crimes as an adult. But the increase in drug-related crimes cancels out any benefit harsh sentences might offer, researchers found.

"Juvenile incarceration is a double-edged sword which deters future property crimes but makes drug convictions more likely in adulthood. Thus, it's hard to make firm policy recommendations ...

Scientists believe a stomach-specific protein plays a major role in the progression of obesity, according to new research in Scientific Reports. The study co-authored by an Indiana University School of Medicine researcher, could help with development of therapeutics that would help individuals struggling with achieving and maintaining weight loss.

Researchers focused on Gastrokine-1 (GKN1) -- a protein produced exclusively and abundantly in the stomach. Previous research has suggested GKN1 is resistant to digestion, allowing it to pass into the intestine and interact with microbes in the gut.

In the Scientific Reports study, researchers show that inhibiting GKN1 produced significant differences in weight and levels of body fat in comparison to when the protein was expressed.

"While ...

Next-generation gene sequencing (NGS) technologies --in which millions of DNA molecules are simultaneously but individually analyzed-- theoretically provides researchers and clinicians the ability to noninvasively identify mutations in the blood stream. Identifying such mutations enables earlier diagnosis of cancer and can inform treatment decisions. Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center researchers developed a new technology to overcome the inefficiencies and high error rates common among next-generation sequencing techniques that have previously limited their clinical application.

To correct for these sequencing errors, the research team from the Ludwig Center and Lustgarten Laboratory at the Johns Hopkins ...

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- A pair of Mayo Clinic studies shed light on something that is typically difficult to see with the eye: respiratory aerosols. Such aerosol particles of varying sizes are a common component of breath, and they are a typical mode of transmission for respiratory viruses like COVID-19 to spread to other people and surfaces.

Researchers who conduct exercise stress tests for heart patients at Mayo Clinic found that exercising at increasing levels of exertion increased the aerosol concentration in the surrounding room. Then also found that a high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) device effectively filtered out the aerosols and decreased the time needed to ...

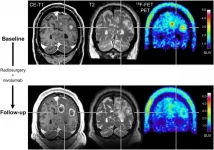

Reston, VA--For patients with brain metastases, amino acid positron emission tomography (PET) can provide valuable information about the effectiveness of state-of-the-art treatments. When treatment monitoring with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is unclear, adding 18F-FET PET can help to accurately diagnose recurring brain metastases and reliably assess patient response. This research was published in The Journal of Nuclear Medicine.

Newer treatment options for patients with brain metastases--such as immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapies--are effective, but can cause a variety of side effects. ...

The human immune system doesn't just protect our health, it reflects it. Each encounter with a potential disease-causing agent causes the body to produce specific immune agents -- proteins known as antibodies and T-cell receptors -- tailor-made to recognize and destroy the invader. Tasked with preventing re-infection, antibodies and T-cell receptors (TCR) from your previous encounters circulate throughout the body indefinitely, like a record of your personal medical history that you carry inside of you.

Clinical pathologist Ramy Arnaout, MD, DPhil, ...