INFORMATION:

This work was supported by internal funds from BWH Pathology, NIH NIGMS R35GM138216, Google Cloud Research Grant, Nvidia GPU Grant Program and the NIH Biomedical Informatics and Data Science Research Training Program (NLM T15LM007092).

Paper cited: Ming, LY et al., "AI-based pathology predicts origins for cancers of unknown primary" Nature DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03512-4

Artificial intelligence system may improve diagnosis of complicated metastatic cancers

Using routinely acquired pathology slides, the model accurately predicts the origin of cancers with unknown primary tumors

2021-05-05

(Press-News.org) In 1 to 2 percent of cancer cases, the primary site of tumor origin cannot be determined. Because many modern cancer therapeutics target primary tumors, the prognosis for a cancer of unknown primary (CUP) is poor, with a median overall survival of 2.7-to-16 months. In order to receive a more specific diagnosis, patients often must undergo extensive diagnostic workups that can include additional laboratory tests, biopsies and endoscopy procedures, which delay treatment. To improve diagnosis for patients with complex metastatic cancers, especially those in low-resource settings, researchers from the Mahmood Lab at the Brigham and Women's Hospital developed an artificial intelligence (AI) system that uses routinely acquired histology slides to accurately find the origins of metastatic tumors while generating a "differential diagnosis," for CUP patients. Research findings are described in Nature.

"Almost every patient that has a cancer diagnosis has a histology slide, which has been the diagnostic standard for over a hundred years. Our work provides a way to leverage universally acquired data and the power of artificial intelligence to improve diagnosis for these complicated cases that typically require extensive diagnostic work-ups," said corresponding author Faisal Mahmood, PhD, of the Division of Computational Pathology at the Brigham and an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School.

The deep-learning-based algorithm developed by the researchers, called Tumor Origin Assessment via Deep Learning (TOAD), simultaneously identifies the tumor as primary or metastatic and predicts its site of origin. The researchers trained their model with gigapixel pathology whole-slide images of tumors from over 22,000 cancer cases, and then tested TOAD in about 6,500 cases with known primaries and analyzed increasingly complicated metastatic cancers to establish utility of the AI model on CUPs. For tumors with known primary origins, the model correctly identified the cancer 83 percent of the time and listed the diagnosis among its top three predictions 96 percent of the time. The researchers then tested the model on 317 CUP cases for which a differential diagnosis was assigned, finding that TOAD's diagnosis agreed with pathologists' reports 61 percent of the time and top-three agreement in 82 percent of cases.

TOAD's performance was largely comparable to the performance reported by several recent studies that used genomic data to predict tumor origins. While genomic-based AI offers an alternative option for aiding diagnoses, genomic testing is not always performed for patients, especially in low-resource settings. The researchers hope to continue training their histology-based model with more cases and engage in clinical trials to determine whether it improves diagnostic capabilities and patients' prognoses.

"The top predictions from the model can accelerate diagnosis and subsequent treatment by reducing the number of ancillary tests that need to be ordered, reducing additional tissue sampling, and the overall time required to diagnose patients, which can be long and stressful," Mahmood said. "Top-three predictions can be used to guide pathologists next steps, and in low-resource settings where pathology expertise may not be available the top prediction could potentially be used to assign a differential diagnosis. This is only the first step in using whole-slide images for AI-assisted cancer origin prediction, and it's a very exciting area with the potential to standardize and improve the diagnotic process."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Catastrophic sea-level rise from Antarctic melting possible with severe global warming

2021-05-05

The Antarctic ice sheet is much less likely to become unstable and cause dramatic sea-level rise in upcoming centuries if the world follows policies that keep global warming below a key END ...

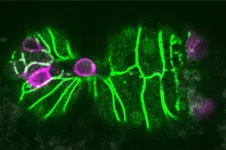

How mitochondria make the cut

2021-05-05

Mitochondria either split in half to multiply within the cell, or cut off their ends to get rid of damaged material. That's the take-away message from EPFL biophysicists in their latest research investigating mitochondrial fission. It's a major departure from the classical textbook explanation of the life cycle of this well-known organelle, the powerhouse of the cell. The results are published today in Nature.

"Until this study, it was poorly understood how mitochondria decide where and when to divide," says EPFL biophysicist Suliana Manley and senior author of the study.

The big question : regulating mitochondrial fission

Mitochondrial fission is important for the proliferation of mitochondria, which is fundamental for cellular growth. As a cell gets bigger, ...

Africa's oldest human burial site uncovered

2021-05-05

The discovery of the earliest human burial site yet found in Africa, by an international team including several CNRS researchers1, has just been announced in the journal Nature. At Panga ya Saidi, in Kenya, north of Mombasa, the body of a three-year-old, dubbed Mtoto (Swahili for 'child') by the researchers, was deposited and buried in an excavated pit approximately 78,000 years ago. Through analysis of sediments and the arrangement of the bones, the research team showed that the body had been protected by being wrapped in a shroud made of perishable material, and that the head had likely rested on an object also of perishable material. Though there are no signs of offerings or ochre, both common at more recent burial ...

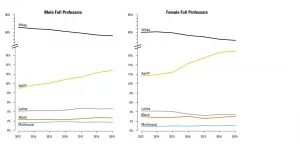

Black and Latinx surgeons continue to hit glass ceiling in America

2021-05-05

Among the upper echelons of academic surgery, Black and Latinx representation has remained flat over the past six years, according to a study published today in JAMA Surgery by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center and University of Florida Health.

The study tracked trends across more than 15,000 faculty in surgery departments across the U.S. between 2013-2019. Although the data revealed modest diversity gains among early-career faculty during this period, especially for Black and Latina women, the percentage of full professors and department chairs identifying as Black or Latinx continued to hover in the single digits. ...

Biologists discover a trigger for cell extrusion

2021-05-05

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- For all animals, eliminating some cells is a necessary part of embryonic development. Living cells are also naturally sloughed off in mature tissues; for example, the lining of the intestine turns over every few days.

One way that organisms get rid of unneeded cells is through a process called extrusion, which allows cells to be squeezed out of a layer of tissue without disrupting the layer of cells left behind. MIT biologists have now discovered that this process is triggered when cells are unable to replicate their DNA during cell division.

The researchers discovered this mechanism in the worm C. elegans, and they showed that ...

Medicaid enrollment during COVID-19 pandemic

2021-05-05

What The Study Did: This study analyzed changes in Medicaid enrollment for all 50 states and the District of Columbia during the first nine months of last year during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Authors: Peggah Khorrami, M.P.H., of the Harvard T.H.Chan School of Public Health in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.9463)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other ...

Stem cells create early human embryo structure in advance for fertility research

2021-05-05

Exeter scientists have discovered a simple, efficient way to recreate the early structure of the human embryo from stem cells in the laboratory. The new approach unlocks news ways of studying human fertility and reproduction.

Stem cells have the ability to turn into different types of cell. Now, in research published in Cell Stem Cell and funded by the Medical Research Council, scientists at the University of Exeter's Living Systems Institute, working with colleagues from the University of Cambridge, have developed a method to organise lab-grown stem cells into an accurate model of the first stage of human embryo development.

The ability to create artificial ...

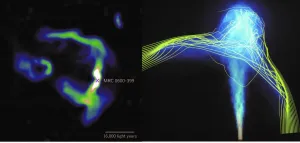

A new window to see hidden side of magnetized universe

2021-05-05

New observations and simulations show that jets of high-energy particles emitted from the central massive black hole in the brightest galaxy in galaxy clusters can be used to map the structure of invisible inter-cluster magnetic fields. These findings provide astronomers with a new tool for investigating previously unexplored aspects of clusters of galaxies.

As clusters of galaxies grow through collisions with surrounding matter, they create bow shocks and wakes in their dilute plasma. The plasma motion induced by these activities can drape intra-cluster magnetic ...

Fast changing smells can teach mice about space

2021-05-05

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute and UCL (University College London) have found that mice can sense extremely fast and subtle changes in the structure of odours and use this to guide their behaviour. The findings, published in Nature today (Wednesday), alter the current view on how odours are detected and processed in the mammalian brain.

Odour plumes, like the steam off a hot cup of coffee, are complex and often turbulent structures, and can convey meaningful information about an animal's surroundings, like the movements of a predator or the location of food sources. But it has previously been assumed that mammalian brains can't fully process these temporal ...

New bonobo genome fine tunes great ape evolution studies

2021-05-05

Chimpanzees and bonobos diverged comparatively recently in great ape evolutionary history. They split into different species about 1.7 million years ago. Some of the distinctions between chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and bonobo (Pan paniscus) lineages have been made clearer by a recent achievement in hominid genomics.

A new bonobo genome assembly has been constructed with a multiplatform approach and without relying on reference genomes. According to the researchers on this project, more than 98% of the genes are now completely annotated and 99% of the gaps are closed.

The ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

RESPIN launches new online course to bridge the gap between science and global environmental policy

[Press-News.org] Artificial intelligence system may improve diagnosis of complicated metastatic cancersUsing routinely acquired pathology slides, the model accurately predicts the origin of cancers with unknown primary tumors