New modeling of Antarctic ice shows unstoppable sea level rise if Paris targets overshot

Study led by UMass Amherst's Rob DeConto is the first to use physics-based model of ice sheet to test Paris Agreement targets

2021-05-05

(Press-News.org) AMHERST, Mass. - The world is currently on track to exceed three degrees Celsius of global warming, and new research led by the University of Massachusetts Amherst's Rob DeConto, co-director of the School of Earth & Sustainability, shows that such a scenario would drastically accelerate the pace of sea-level rise by 2100. If the rate of global warming continues on its current trajectory, we will reach a tipping point by 2060, past which these consequences would be "irreversible on multi-century timescales."

The new paper, published today in Nature, models the impact of several different warming scenarios on the Antarctic Ice Sheet, including the Paris Agreement target of two degrees Celsius of warming, an aspirational 1.5 degree scenario, and our current course which, if not altered, will yield three or more degrees of warming. If the more optimistic 1.5 and 2 degree Paris Agreement temperature targets are achieved, the Antarctic Ice Sheet would contribute between 6 and 11 centimeters of sea level rise by 2100. But if the current course toward 3 degrees is maintained, the model points to a major jump in melting. Unless ambitious action to rein in warming begins by 2060, no human intervention, including geoengineering, would be able to stop 17 to 21 centimeters of sea-level rise from Antarctic ice melt alone by 2100. The implications of exceeding Paris Agreement warming targets become even more stark on longer timescales. Antarctica contributes about 1 meter of sea level rise by 2300 if warming is limited to 2 degrees or less, but reaches globally catastrophic levels of 10 meters or more under a more extreme warming scenario with no mitigation of greenhouse-gas emissions.

DeConto and colleagues' research shows the very architecture of the Antarctic Ice Sheet itself plays a key role in ice loss. Ice flows slowly downhill, and the Antarctic Ice Sheet naturally creeps into the ocean, where it begins to melt. What keeps that ocean-bound ice flowing slowly is a ring of buttressing ice shelves, which float in the ocean but hold back the upstream glacial ice by scraping on shallow sea-floor features. Those buttressing ice shelves act both as dams that keep the sheet from sliding rapidly into the ocean, and as supports that keep the edges of the ice sheet from collapsing.

But as warming increases, the ice shelves thin and become more fragile. Meltwater on their surfaces can deepen crevasses and cause them to disintegrate entirely. This not only lets the ice sheet flow toward the warming ocean more quickly, it allows the exposed edges of the ice sheet to break off or "calve" into the ocean, adding to sea level rises. These processes of melting and ice shelf loss, followed by faster glacial flow and rapid calving are seen on Greenland today, but they haven't become widespread on the colder Antarctic ice sheet -- at least not yet. DeConto points out that "if the world continues to warm, the huge glaciers on Antarctica might begin behaving like their smaller counterparts on Greenland, which would be disastrous in terms of sea level rise." The authors of the study, which was supported by funding from the National Science Foundation and the NASA Sea Level Change Science Team, write that missing Paris Agreement temperature targets and allowing extensive loss of the buttressing ice shelves "represents a possible tipping point in Antarctica's future."

INFORMATION:

Contact: Rob DeConto, deconto@geo.umass.edu

Daegan Miller, drmiller@umass.edu

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-05

In 1 to 2 percent of cancer cases, the primary site of tumor origin cannot be determined. Because many modern cancer therapeutics target primary tumors, the prognosis for a cancer of unknown primary (CUP) is poor, with a median overall survival of 2.7-to-16 months. In order to receive a more specific diagnosis, patients often must undergo extensive diagnostic workups that can include additional laboratory tests, biopsies and endoscopy procedures, which delay treatment. To improve diagnosis for patients with complex metastatic cancers, especially those in low-resource settings, researchers from the Mahmood Lab at the Brigham and Women's Hospital developed an artificial intelligence (AI) system that uses routinely acquired histology slides to accurately find the origins of metastatic ...

2021-05-05

The Antarctic ice sheet is much less likely to become unstable and cause dramatic sea-level rise in upcoming centuries if the world follows policies that keep global warming below a key END ...

2021-05-05

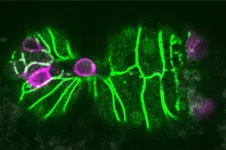

Mitochondria either split in half to multiply within the cell, or cut off their ends to get rid of damaged material. That's the take-away message from EPFL biophysicists in their latest research investigating mitochondrial fission. It's a major departure from the classical textbook explanation of the life cycle of this well-known organelle, the powerhouse of the cell. The results are published today in Nature.

"Until this study, it was poorly understood how mitochondria decide where and when to divide," says EPFL biophysicist Suliana Manley and senior author of the study.

The big question : regulating mitochondrial fission

Mitochondrial fission is important for the proliferation of mitochondria, which is fundamental for cellular growth. As a cell gets bigger, ...

2021-05-05

The discovery of the earliest human burial site yet found in Africa, by an international team including several CNRS researchers1, has just been announced in the journal Nature. At Panga ya Saidi, in Kenya, north of Mombasa, the body of a three-year-old, dubbed Mtoto (Swahili for 'child') by the researchers, was deposited and buried in an excavated pit approximately 78,000 years ago. Through analysis of sediments and the arrangement of the bones, the research team showed that the body had been protected by being wrapped in a shroud made of perishable material, and that the head had likely rested on an object also of perishable material. Though there are no signs of offerings or ochre, both common at more recent burial ...

2021-05-05

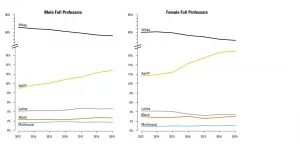

Among the upper echelons of academic surgery, Black and Latinx representation has remained flat over the past six years, according to a study published today in JAMA Surgery by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center and University of Florida Health.

The study tracked trends across more than 15,000 faculty in surgery departments across the U.S. between 2013-2019. Although the data revealed modest diversity gains among early-career faculty during this period, especially for Black and Latina women, the percentage of full professors and department chairs identifying as Black or Latinx continued to hover in the single digits. ...

2021-05-05

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- For all animals, eliminating some cells is a necessary part of embryonic development. Living cells are also naturally sloughed off in mature tissues; for example, the lining of the intestine turns over every few days.

One way that organisms get rid of unneeded cells is through a process called extrusion, which allows cells to be squeezed out of a layer of tissue without disrupting the layer of cells left behind. MIT biologists have now discovered that this process is triggered when cells are unable to replicate their DNA during cell division.

The researchers discovered this mechanism in the worm C. elegans, and they showed that ...

2021-05-05

What The Study Did: This study analyzed changes in Medicaid enrollment for all 50 states and the District of Columbia during the first nine months of last year during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Authors: Peggah Khorrami, M.P.H., of the Harvard T.H.Chan School of Public Health in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.9463)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other ...

2021-05-05

Exeter scientists have discovered a simple, efficient way to recreate the early structure of the human embryo from stem cells in the laboratory. The new approach unlocks news ways of studying human fertility and reproduction.

Stem cells have the ability to turn into different types of cell. Now, in research published in Cell Stem Cell and funded by the Medical Research Council, scientists at the University of Exeter's Living Systems Institute, working with colleagues from the University of Cambridge, have developed a method to organise lab-grown stem cells into an accurate model of the first stage of human embryo development.

The ability to create artificial ...

2021-05-05

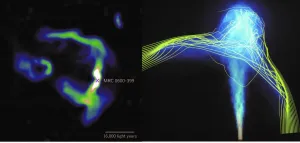

New observations and simulations show that jets of high-energy particles emitted from the central massive black hole in the brightest galaxy in galaxy clusters can be used to map the structure of invisible inter-cluster magnetic fields. These findings provide astronomers with a new tool for investigating previously unexplored aspects of clusters of galaxies.

As clusters of galaxies grow through collisions with surrounding matter, they create bow shocks and wakes in their dilute plasma. The plasma motion induced by these activities can drape intra-cluster magnetic ...

2021-05-05

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute and UCL (University College London) have found that mice can sense extremely fast and subtle changes in the structure of odours and use this to guide their behaviour. The findings, published in Nature today (Wednesday), alter the current view on how odours are detected and processed in the mammalian brain.

Odour plumes, like the steam off a hot cup of coffee, are complex and often turbulent structures, and can convey meaningful information about an animal's surroundings, like the movements of a predator or the location of food sources. But it has previously been assumed that mammalian brains can't fully process these temporal ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] New modeling of Antarctic ice shows unstoppable sea level rise if Paris targets overshot

Study led by UMass Amherst's Rob DeConto is the first to use physics-based model of ice sheet to test Paris Agreement targets