(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. - A study designed to enroll an equal number of Black and white men with advanced prostate cancer confirms key findings that have been evident in retrospective analyses and suggest potential new avenues for treating Black patients who disproportionately die of the disease.

Researchers at Duke Cancer Institute enrolled 50 Black and 50 white men with advanced prostate cancer to test whether there were outcome differences on treatment with the hormone therapy abiraterone acetate plus the steroid prednisone. In retrospective data reviews, the Duke researchers had previously found racial differences in PSA responses among advanced prostate cancer patients.

Publishing online in the journal Cancer, the researchers confirmed trends indicating that Black men's PSA levels dropped further and more frequently than those of white men undergoing the therapy. These PSA changes, however, did not result in differences in disease progression or overall survival times.

But the survival finding has an important subtlety, said lead author Daniel George, M.D., professor in the departments of Medicine and Surgery at Duke University School of Medicine. George noted that most drug studies among prostate cancer patients include a small fraction of Black men that is far lower than their numbers in the larger population.

Exclusions typically result because Black men with prostate cancer are more likely to have other illnesses such as diabetes and high blood pressure, which study leaders often fear could put them at higher risk for complications. Additionally, there are deep historic and cultural reasons that Black men tend to decline participation in clinical studies.

For their study, however, the Duke team -- including senior author Andrew Armstrong, M.D., professor in the departments of Medicine and Surgery -- found that Black men were eager to join the clinical trial.

They were able to enroll a much larger proportion of Black men than what most studies include, in part because the study was addressing a question pertaining to race. And they did not exclude men with co-existing conditions, asserting that since the treatment is FDA approved for this population, they should be inclusive of the patients they see in practice.

"When you look at the overall survival data for our study, they're equal between Black and white men," George said. "But given the prevalence of coexisting conditions in the Black men we enrolled, mortality should have actually been higher for them.

"Our finding that it was not higher is telling -- it suggests Black men with prostate cancer can fare just as well as whites, even with other health issues," George said. "And it signals that future studies should consider enrolling Black men despite these often-disqualifying conditions."

George said the researchers also identified a possible marker of ancestry-dependent treatment outcomes that could help explain why Black men respond more readily to hormone therapy, potentially pointing to new ways to address advanced prostate cancer in Black men.

"We need to understand how genetic ancestry might affect treatment outcomes -- especially disease responsiveness in prostate cancer -- because we are now using and studying these therapies earlier in the disease where we have the opportunity to cure patients," George said.

"If there is a subgroup of patients with an ancestry-based predisposition for potential better response, we need to understand that. But to do so, we will need greater genetic diversity in our future study populations, especially among those with African ancestry. We aren't going to fully understand this genetic complexity by solely enrolling men with European ancestry."

INFORMATION:

In addition to George, study authors include Susan Halabi, Elisabeth Heath, A. Oliver Sartor, Guru Sonpavde, Devika Das, Rhonda L. Bitting, William Berry, Patrick Healy, Monika Anand, Carol Winters, Colleen Riggan, Julie Kephart, Rhonda Wilder, Kellie Shobe, Julia Rasmussen, Matthew Milowsky, Mark Fleming, James Bearden, Michael Goodman, Tian Zhang, Michael R. Harrison, Megan McNamara, Dadong Zhang, Bonnie L. LaCroix, Rick A. Kittles, Brendon M. Patierno, Alexander B. Sibley, Steven R. Patierno, Kouros Owzar, Terry Hyslop, Jennifer A. Freedman, Andrew J. Armstrong.

The study received funding support from Janssen Scientific Affairs, which markets abiraterone acetate; the Department of Defense (W81XWH-09-1-0152, W81XWH-14-2-0198); the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (1P20-CA202925-01A1); and a Prostate Cancer Foundation Movember Challenge Award.

Armstrong reports a paid consultancy with Janssen among other disclosures itemized in the study; George receives study support from the company via Duke.

"The overarching idea of this research project is to influence different biological processes at the cellular level (i.e., wound healing, brain synapses or nervous system responses) by developing timely engineering applications", explains 4D-BIOMAP's lead researcher, Daniel García González from the UC3M's Department of Continuum Mechanics and Structural Analysis.

The so-called magneto-active polymers are revolutionising the fields of solid mechanics and materials science. These composites consist of a polymeric matrix (i.e., an elastomer) that contains magnetic particles (i.e., iron) that react mechanically ...

The study says differences in children's brains, which affect their sensitivity to pressure and rewards, and differences in the way they process information, make it more likely they will admit to crimes they didn't commit when incentivized to do so.

These developmental vulnerabilities mean solicitors and barristers should get extra support to help them better support young people deciding whether to admit guilt.

Dr Rebecca Helm, from the University of Exeter, who led the research, published in the Journal of Law and Society, said: "The criminal justice system relies almost exclusively on the autonomy of defendants, rather than accuracy, when justifying convictions ...

DURHAM, N.H.-- As climate change continues to trigger the rise in temperature, increase drier conditions and shift precipitation patterns, adapting to new conditions will be critical for the long-term survival of most species. Researchers at the University of New Hampshire found that to live in hotter more desert-like surroundings, and exist without water, there is more than one genetic mechanism allowing animals to adapt. This is important not only for their survival but may also provide important biomedical groundwork to develop gene therapies to treat human dehydration related illnesses, like kidney disease.

"To reference a familiar phrase, it tells us that there is more than one way to bake a ...

Reducing net greenhouse gas emissions to zero as soon as possible and achieving "carbon neutrality" is the key to addressing global warming and climate change. The ocean is the largest active carbon pool on the planet, with huge potential to help achieve negative emissions by serving as a carbon sink.

Recently, researchers found that adding a small amount of aluminum to achieve concentrations in the 10x nanomolar (nM) range can increase the net fixation of CO2 by marine diatoms and decrease their decomposition, thus improving the ocean's ability to absorb CO2 and sequester ...

Students struggling academically benefited most when schools around the world transitioned from classroom teaching to online learning in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the switch also didn't negatively impact higher achievers.

A new study has analysed the impact of online learning during the pandemic by crunching data at three middle schools in China, which administered different educational practices for about 7 weeks during the country's Covid-19 lockdown.

Online learning was shown to have a positive impact on overall student performance when compared to not receiving any support from school during lockdown, and the best results were achieved by ...

Australia's 'black summer' of bushfires was depicted on the front pages of the world's media with images of wildlife and habitat destruction, caused by climate change, while in Australia the toll on ordinary people remained the visual front-page focus.

QUT visual communication researcher Dr TJ Thomson compared the front-page bushfire imagery of the Sydney Morning Herald over three months from November 10, 2019 to January 31 2020 with 119 front pages from international media from the start of January, when the world sat up and took notice, to January 31.

"The international sample of front pages included the Americas and Europe (about 90 per cent) representing Australia's 'black summer'. Asia represented around 7 per cent of the international ...

Transitioning from fossil fuels to a clean hydrogen economy will require cheaper and more efficient ways to use renewable sources of electricity to break water into hydrogen and oxygen.

But a key step in that process, known as the oxygen evolution reaction or OER, has proven to be a bottleneck. Today it's only about 75% efficient, and the precious metal catalysts used to accelerate the reaction, like platinum and iridium, are rare and expensive.

Now an international team led by scientists at Stanford University and the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory has developed a ...

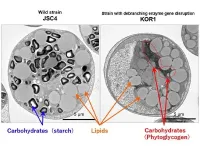

A cross-institutional collaboration has developed a technique to repartition carbon resources from carbohydrates to lipids in microalgae. It is hoped that this method can be applied to biofuel production. This discovery was the result of a collaboration between a research group at Kobe University's Engineering Biology Research Center consisting of Project Assistant Professor KATO Yuichi and Professor HASUNUMA Tomohisa et al., and Senior Researcher SATOH Katsuya et al. at the Takasaki Advanced Radiation Research Institute of the Quantum Beam Science Research Directorate ...

Scientists are calling for more stringent pesticide bans to lower deaths caused by deliberately ingesting toxic agricultural chemicals, which account for one fifth of global suicides.

A NHMRC funded study, in which the University of South Australia analysed the patient plasma pesticide concentrations, has identified discrepancies in World Health Organization (WHO) classifications of pesticide hazards that are based on animal doses rather than human data.

As a result, up to five potentially lethal pesticides are still being used in developing countries in the Asia Pacific, where self-poisonings account for up to two thirds of suicides.

In ...

New research from the University of Virginia School of Medicine reveals why sleep can put people with epilepsy at increased risk of sudden death.

Both sleep and seizures work together to slow the heart rate, the researchers found. Seizures also disrupt the body's natural regulation of sleep-related changes. Together, in some instances, this can prove deadly, causing Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy, or SUDEP.

"We have been trying to better understand the cardiac changes around the time of a seizure in patients with epilepsy. When we looked ...