Epilepsy research reveals why sleep increases risk of sudden death

2021-05-06

(Press-News.org) New research from the University of Virginia School of Medicine reveals why sleep can put people with epilepsy at increased risk of sudden death.

Both sleep and seizures work together to slow the heart rate, the researchers found. Seizures also disrupt the body's natural regulation of sleep-related changes. Together, in some instances, this can prove deadly, causing Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy, or SUDEP.

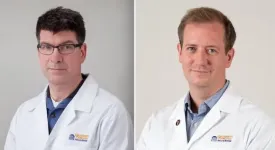

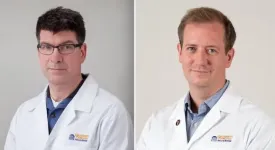

"We have been trying to better understand the cardiac changes around the time of a seizure in patients with epilepsy. When we looked at the heart rates for patients with epilepsy admitted to the hospital, many of them develop tachycardia [a fast heart rate] following a seizure, but a subset of patients have a decreased heart rate. This decline was more pronounced when the patients were asleep," said Andrew Schomer, MD, of UVA's Department of Neurology and the UVA Brain Institute. "The mechanism of SUDEP, or Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy, is still not fully understood. We know there is an increased risk during sleep and if seizures are poorly controlled. Hopefully with further study we can try to identify individuals who are at an increased risk and work to prevent this devastating outcome."

Understanding SUDEP in Sleep

Doctors have been unsure how seizures in sleep can cause death, such as was the case with young Disney Channel star Cameron Boyce in 2019. He died of SUDEP while sleeping at age 20. (While SUDEP can occur when patients with epilepsy are awake, the majority of cases occur during sleep.)

To better understand the effect of sleep seizures, UVA researchers led by Schomer and Mark Quigg, MD, MSc, monitored the brain and heart activity of people with epilepsy as they slept. The patients were admitted to the UVA Epilepsy Monitoring Unit between February 2018 and August 2019, and all were 17 or older.

In total, the researchers evaluated 101 sleep seizures in 41 patients, with a median age of 40.5. The participants were, on average, diagnosed more than 20 years previously.

The researchers monitored how deeply the patients were sleeping when the seizures occurred. Some seizures caused heart rates to increase. But the greater sleep depth prior to a seizure, the slower the patient's heart rate was likely to become, the scientists found.

The results suggest that seizures during sleep are more likely to lead to dangerously slow heart rate. The effect of the seizure is secondary to the natural slowing of the heart rate during sleep, the researchers believe, but the two together can, in some instances, prove deadly.

More study is needed to better understand the variables involved and to better determine what is occurring in individual patients, the researchers say. But the findings represent an important advance in the effort to prevent SUDEP during sleep.

"People with poorly controlled seizures have the greatest risk of SUDEP, and seizures during sleep may hold the higher risk," said Quigg, of UVA's Department of Neurology and the UVA Brain Institute. "Our findings can direct further research to determine how the heart's and lung's control systems fail during sleep-related seizures in order to help prevent SUDEP."

INFORMATION:

Findings Published

The researchers have published their findings in the scientific journal Epilepsia. The research team consisted of Schomer, Morgan Lynch, Stephanie Lowenhaupt, Juliana Leonardo, Valentina Baljak, Matthew Clark, Jaideep Kapur and Quigg.

The work was supported by the National Institute of Health's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke via its NeuroNEXT program, grant 4U10NS077260-07.

To keep up with the latest medical research news from UVA, subscribe to the Making of Medicine blog at http://makingofmedicine.virginia.edu.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-06

Proteins are the workhorses of cells, responsible for almost all biological functions that make life possible.

Understanding how specific proteins work is key to disease prevention and treatment, allowing us to lead longer, healthier lives.

Yet scientists still know nothing or very little about thousands of proteins that exist in our bodies and their role in keeping us alive.

Now researchers from Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University have uncovered a new protein analysis tool - coined the Bacterial Growth Inhibition Screen (BGIS) - that could fast-track the process of assessing proteins. The tool allows for quick and efficient basic characterisation of protein function with no special equipment or cost involved.

Dr Ferdinand Kappes of XJTLU's ...

2021-05-06

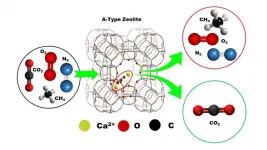

It is now well known that carbon dioxide is the biggest contributor to climate change and originates primarily from burning of fossil fuels. While there are ongoing efforts around the world to end our dependence on fossil fuels as energy sources, the promise of green energy still lies in the future. Can something be done in the meantime to reduce the concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere?

It would, in fact, be great if the CO2 in the atmosphere could simply be adsorbed! Turns out, this is exactly what direct air capture (DAC), or the capture of CO2 under ambient conditions, aims to do. However, no such material with the ability to adsorb CO2 efficiently under DAC ...

2021-05-06

In Alzheimer's disease, neurons in the brain die. Largely responsible for the death of neurons are certain protein deposits in the brains of affected individuals: So-called beta-amyloid proteins, which form clumps (plaques) between neurons, and tau proteins, which stick together the inside of neurons. The causes of these deposits are as yet unclear. In addition, a rapidly progressive atrophy, i.e. a shrinking of the brain volume, can be observed in affected persons. Alzheimer's symptoms such as memory loss, disorientation, agitation and challenging behavior are the consequences.

Scientists at the DZNE led by Prof. Michael Wagner, head of a research group at the DZNE and senior ...

2021-05-06

Determining safe yet effective drug dosages for children is an ongoing challenge for pharmaceutical companies and medical doctors alike. A new drug is usually first tested on adults, and results from these trials are used to select doses for pediatric trials. The underlying assumption is typically that children are like adults, just smaller, which often holds true, but may also overlook differences that arise from the fact that children's organs are still developing.

Compounding the problem, pediatric trials don't always shed light on other differences that can affect recommendations for drug doses. There are many factors that limit children's participation in drug trials - for instance, some diseases simply ...

2021-05-06

AURORA, Colo. (May 6, 2021) - Scientists examining the remains of 36 bubonic plague victims from a 16th century mass grave in Germany have found the first evidence that evolutionary adaptive processes, driven by the disease, may have conferred immunity on later generations of people from the region.

"We found that innate immune markers increased in frequency in modern people from the town compared to plague victims," said the study's joint-senior author Paul Norman, PhD, associate professor in the Division of Personalized Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. "This suggests these markers might have evolved to resist the plague."

The study, done in conjunction with the Max Planck Institute in Germany, was published online Thursday in the journal Molecular ...

2021-05-06

Ultrasound is an indispensable tool for the life sciences and various industrial applications due to its non-destructive, high contrast, and high resolution qualities. A persistent challenge over the years has been how to increase the resolution of an acoustic endoscope without drastically increasing the footprint of the probe, or risking the robustness of the ultrasonic transducer. In recent years, a host of all-optical ultrasonic imaging techniques have emerged - which generally utilise pulsed lasers and optical cavities to excite and detect ultrasound waves - without sacrificing device footprint, sensitivity, or the integrity of the transducer. Thus far these powerful techniques have achieved imaging resolutions on microscopic-mesoscopic length ...

2021-05-06

Researchers at the University of Eastern Finland have discovered previously unknown non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) involved in regulating the gene expression of vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF), the master regulators of angiogenesis. The study, conducted by the research groups of Associate Professor Minna Kaikkonen-Määttä and Academy Professor Seppo Ylä-Herttuala, provides a better understanding of the complex interplay of ncRNAs with gene regulation, which might open up novel therapeutic approaches in the future. The results were published in the Molecular and Cellular Biology Journal.

Over the past years, the development of next generation ...

2021-05-06

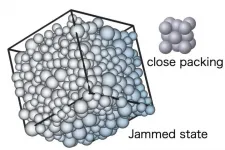

Researchers at Chinese Academy of Science and Osaka University show that, unlike the crystalline close packing of spheres, random close packing or jamming of spheres in a container can take place in a broad range of densities and anisotropies. Furthermore, they show that such diverse jammed states are all just marginally stable and exhibit common universal critical properties.

Osaka, Japan - Scientists at the theoretical institutes, Chinese Academy of Science and Cybermedia Center at Osaka University performed extensive computer simulations to generate and examine random packing of spheres. They show that the "jamming" ...

2021-05-06

A KAIST research team has developed a new technology that enables to process a large-scale graph algorithm without storing the graph in the main memory or on disks. Named as T-GPS (Trillion-scale Graph Processing Simulation) by the developer Professor Min-Soo Kim from the School of Computing at KAIST, it can process a graph with one trillion edges using a single computer.

Graphs are widely used to represent and analyze real-world objects in many domains such as social networks, business intelligence, biology, and neuroscience. As the number of graph applications increases rapidly, developing and testing new graph algorithms is becoming more important than ever before. Nowadays, many industrial ...

2021-05-06

Trust, safety and security are the most important factors affecting passengers' attitudes towards self-driving cars. Younger people felt their personal security to be significantly better than older people.

The findings are from a Finnish study into passengers' attitudes towards, and experiences of, self-driving cars. The study is also the first in the world to examine passengers' experiences of self-driving cars in winter conditions.

The findings were published in Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. The study was carried out in collaboration between the University of Eastern Finland and Tampere University.

Self-driving cars face huge expectations in Europe and the United States, which is why passengers' ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Epilepsy research reveals why sleep increases risk of sudden death