Children likely to be pleading guilty when innocent, study argues

2021-05-06

(Press-News.org) The study says differences in children's brains, which affect their sensitivity to pressure and rewards, and differences in the way they process information, make it more likely they will admit to crimes they didn't commit when incentivized to do so.

These developmental vulnerabilities mean solicitors and barristers should get extra support to help them better support young people deciding whether to admit guilt.

Dr Rebecca Helm, from the University of Exeter, who led the research, published in the Journal of Law and Society, said: "The criminal justice system relies almost exclusively on the autonomy of defendants, rather than accuracy, when justifying convictions via guilty plea. But children don't necessarily have the capacity to make truly autonomous decisions in this context, where they face a variety of really compelling pressures. Children are likely to misunderstand information, not admit they don't understand and agree with statements, or succumb to pressure from others and the system. They may be unsure whether they have committed a legal offence, or whether there is a defence they can rely on.

"The incentives offered to encourage guilty pleas, and time pressures associated with them, are likely to interact with developmental vulnerabilities in children to create an environment in which innocent children are systematically pleading guilty."

In England and Wales, the majority of defendants plead guilty rather than contest their guilt at trial. In 2019, 61 per cent of child defendants in the Crown Court pleaded guilty (with 58 per cent pleading guilty at their first hearing), and 47 per cent of child defendants in the Youth Court pleaded guilty at their first hearing.

Children who enter a guilty plea at the earliest possible opportunity to do so can get a reduction in their sentence of up to a third compared to what they would receive if convicted at trial, or receive a referral order or a youth rehabilitation order when they would face a custodial sentence at trial. The study says that these reductions are not appropriate in children and have the potential to create pressures to plead. It would be better to award tailored reductions to children based on less prescriptive guidelines and individual case circumstances, including defendant age.

Dr Helm said: "We now have a fairly good understanding of decision-making in children, and how it differs from decision-making in adults. It is therefore not appropriate to continue to put children accused of criminal offences in situations where it is predictable that they will 'admit' guilt even when innocent, and then punish them as if they are guilty. Ensuring children have appropriate and tailored protection when deciding whether to plead guilty is really important."

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-06

DURHAM, N.H.-- As climate change continues to trigger the rise in temperature, increase drier conditions and shift precipitation patterns, adapting to new conditions will be critical for the long-term survival of most species. Researchers at the University of New Hampshire found that to live in hotter more desert-like surroundings, and exist without water, there is more than one genetic mechanism allowing animals to adapt. This is important not only for their survival but may also provide important biomedical groundwork to develop gene therapies to treat human dehydration related illnesses, like kidney disease.

"To reference a familiar phrase, it tells us that there is more than one way to bake a ...

2021-05-06

Reducing net greenhouse gas emissions to zero as soon as possible and achieving "carbon neutrality" is the key to addressing global warming and climate change. The ocean is the largest active carbon pool on the planet, with huge potential to help achieve negative emissions by serving as a carbon sink.

Recently, researchers found that adding a small amount of aluminum to achieve concentrations in the 10x nanomolar (nM) range can increase the net fixation of CO2 by marine diatoms and decrease their decomposition, thus improving the ocean's ability to absorb CO2 and sequester ...

2021-05-06

Students struggling academically benefited most when schools around the world transitioned from classroom teaching to online learning in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the switch also didn't negatively impact higher achievers.

A new study has analysed the impact of online learning during the pandemic by crunching data at three middle schools in China, which administered different educational practices for about 7 weeks during the country's Covid-19 lockdown.

Online learning was shown to have a positive impact on overall student performance when compared to not receiving any support from school during lockdown, and the best results were achieved by ...

2021-05-06

Australia's 'black summer' of bushfires was depicted on the front pages of the world's media with images of wildlife and habitat destruction, caused by climate change, while in Australia the toll on ordinary people remained the visual front-page focus.

QUT visual communication researcher Dr TJ Thomson compared the front-page bushfire imagery of the Sydney Morning Herald over three months from November 10, 2019 to January 31 2020 with 119 front pages from international media from the start of January, when the world sat up and took notice, to January 31.

"The international sample of front pages included the Americas and Europe (about 90 per cent) representing Australia's 'black summer'. Asia represented around 7 per cent of the international ...

2021-05-06

Transitioning from fossil fuels to a clean hydrogen economy will require cheaper and more efficient ways to use renewable sources of electricity to break water into hydrogen and oxygen.

But a key step in that process, known as the oxygen evolution reaction or OER, has proven to be a bottleneck. Today it's only about 75% efficient, and the precious metal catalysts used to accelerate the reaction, like platinum and iridium, are rare and expensive.

Now an international team led by scientists at Stanford University and the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory has developed a ...

2021-05-06

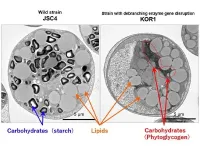

A cross-institutional collaboration has developed a technique to repartition carbon resources from carbohydrates to lipids in microalgae. It is hoped that this method can be applied to biofuel production. This discovery was the result of a collaboration between a research group at Kobe University's Engineering Biology Research Center consisting of Project Assistant Professor KATO Yuichi and Professor HASUNUMA Tomohisa et al., and Senior Researcher SATOH Katsuya et al. at the Takasaki Advanced Radiation Research Institute of the Quantum Beam Science Research Directorate ...

2021-05-06

Scientists are calling for more stringent pesticide bans to lower deaths caused by deliberately ingesting toxic agricultural chemicals, which account for one fifth of global suicides.

A NHMRC funded study, in which the University of South Australia analysed the patient plasma pesticide concentrations, has identified discrepancies in World Health Organization (WHO) classifications of pesticide hazards that are based on animal doses rather than human data.

As a result, up to five potentially lethal pesticides are still being used in developing countries in the Asia Pacific, where self-poisonings account for up to two thirds of suicides.

In ...

2021-05-06

New research from the University of Virginia School of Medicine reveals why sleep can put people with epilepsy at increased risk of sudden death.

Both sleep and seizures work together to slow the heart rate, the researchers found. Seizures also disrupt the body's natural regulation of sleep-related changes. Together, in some instances, this can prove deadly, causing Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy, or SUDEP.

"We have been trying to better understand the cardiac changes around the time of a seizure in patients with epilepsy. When we looked ...

2021-05-06

Proteins are the workhorses of cells, responsible for almost all biological functions that make life possible.

Understanding how specific proteins work is key to disease prevention and treatment, allowing us to lead longer, healthier lives.

Yet scientists still know nothing or very little about thousands of proteins that exist in our bodies and their role in keeping us alive.

Now researchers from Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University have uncovered a new protein analysis tool - coined the Bacterial Growth Inhibition Screen (BGIS) - that could fast-track the process of assessing proteins. The tool allows for quick and efficient basic characterisation of protein function with no special equipment or cost involved.

Dr Ferdinand Kappes of XJTLU's ...

2021-05-06

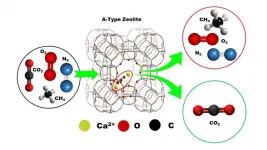

It is now well known that carbon dioxide is the biggest contributor to climate change and originates primarily from burning of fossil fuels. While there are ongoing efforts around the world to end our dependence on fossil fuels as energy sources, the promise of green energy still lies in the future. Can something be done in the meantime to reduce the concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere?

It would, in fact, be great if the CO2 in the atmosphere could simply be adsorbed! Turns out, this is exactly what direct air capture (DAC), or the capture of CO2 under ambient conditions, aims to do. However, no such material with the ability to adsorb CO2 efficiently under DAC ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Children likely to be pleading guilty when innocent, study argues