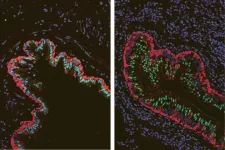

(Press-News.org) A team of researchers from UCLA, Cedars-Sinai and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation has developed a first-of-its-kind molecular catalog of cells in healthy lungs and the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis.

The catalog, described today in the journal Nature Medicine, reveals new subtypes of cells and illustrates how the disease changes the cellular makeup of the airways. The findings could help scientists in their search for specific cell types that represent prime targets for genetic and cell therapies for cystic fibrosis.

"This new research has provided us with valuable insights into the cellular makeup of both healthy and diseased airways," said Dr. Brigitte Gomperts, a co-senior author of the study and a member of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA. "If you can understand how things work in a state of health, it becomes easier to see what cellular and molecular changes occur in a disease state."

A progressive genetic disorder that affects more than 70,000 people worldwide, cystic fibrosis results from mutations to the CFTR gene. Cells that contain the defective protein encoded by the gene produce unusually thick and sticky mucus that builds up in the lungs and other organs. This mucus clogs the airways, trapping germs and bacteria that can cause life-threatening infections and irreversible lung damage.

While several new therapies can partially restore the function of these damaged proteins, easing symptoms of the disease, slowing its progression and improving quality of life, these treatments only work in people with some of the many CFTR mutations that can cause cystic fibrosis.

"We have made tremendous progress in the development of treatments for the underlying cause of cystic fibrosis, but many people cannot benefit from these medicines," said John (Jed) Mahoney, a senior co-author of the paper and head of the stem cell biology team at the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics Lab. "This research provides critical insight into how the disease alters the cellular makeup of the airways, which will enable scientists to better target the next generation of transformative therapies for all people with cystic fibrosis."

The research team was assembled through the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation's Epithelial Stem Cell Consortium, which brings together scientists from across the U.S. in an ongoing effort to identify different subtypes of stem cells in the lungs and study their function. Because these cells can self-renew and produce a continuous supply of specialized cells that maintain, repair and regenerate the airways, therapies aimed at correcting CFTR mutations in stem cells hold the best hope for a one-time, universal treatment for the disease.

"This catalog represents an important step toward identifying those rare stem cells that regenerate the airways over a person's lifetime," said Gomperts, who is also a professor of pediatrics and pulmonary medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. "We suspect these cells could be targets for future therapies that may provide a long-term correction to the mutation that causes this disease."

'Un-blending' a smoothie: How the catalog was created

For the study, Gomperts, Mahoney and their co-senior authors, Barry Stripp of Cedars-Sinai and Kathrin Plath of UCLA, compared tissue samples taken from lungs removed from 19 people with cystic fibrosis, all of whom had received lung transplants, with samples taken from healthy lungs donated by 19 individuals who had died from other causes.

Researchers at the three institutions employed similar but distinct methods to break these tissues down and examine them using a technology called single-cell RNA sequencing, which allowed them to analyze thousands of cells in tandem and classify them into subtypes based on their gene expression patterns -- this is, which genes are turned on and off.

"The process is analogous to taking a smoothie and 'un-blending' it to discover all the ingredients it contains and measure how much of each ingredient was used," said Plath, a professor of biological chemistry and a member of the UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center.

Using a novel computer-based bioinformatics approach to compare the gene expressions patterns of the various cells, the team was able to create a catalog of the cell types and subtypes present in healthy airways and those affected by cystic fibrosis, including some previously unknown subtypes that illuminate how the disease alters the cellular landscape of the airways.

"We were surprised to find that the airways of people with cystic fibrosis showed differences in the types and proportions of basal cells, a cell category that includes stem cells responsible for repairing and regenerating upper airway tissue, compared with airways of people without this disease," said Stripp, a professor of medicine and director of the lung stem cell program at the Cedars-Sinai Board of Governors Regenerative Medicine Institute.

Specifically, the researchers discovered that among the basal cell populations, there was a relative overabundance of cells that appear to be transitioning from basal stem cells into specialized ciliated cells, which use their finger-like projections to clear mucus out of the lungs.

"We suspect that changes the basal cells undergo to replenish ciliated cells represent an unsuccessful attempt to clear mucus that typically accumulates in airways of patients with cystic fibrosis," Stripp said.

The increase in transitioning cells provides further evidence suggesting that expression of the mutated CFTR gene disrupts normal function of the airways, leading to changes in the way that basal stem cells produce specialized cells.

Moving forward, the researchers will continue to study the new data for insights into how cystic fibrosis alters the cellular landscape of the airways -- including why this unsuccessful transition occurs-- and to identify the long-lived basal stem cells that would be the ideal target for a CFTR gene correction.

INFORMATION:

The co-first authors of the study were Gianni Carraro from Cedars-Sinai and Justin Langerman from UCLA.

This research was supported by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, the W.M. Keck Foundation, Celgene, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, a Parker B. Francis Foundation Fellowship, a UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center Rose Hills Foundation Graduate Scholarship and the UCLA Tumor Cell Biology Training Program.

Obesity may be a stronger risk factor for death, severe pneumonia and the need for intubation in men than in women with COVID-19, according to a study published in the European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

An analysis of a cohort of 3530 COVID-19 patients showed that both moderate (BMI of 35/m2 or higher) and severe obesity (BMI of 40kg/m2 and higher) in men but only severe obesity in women (BMI of 40kg/m2 and higher) was associated greater risk of developing severe disease, needing intubation and dying from COVID-19 in hospital.

Previous research demonstrated that obesity is a risk factor for hospitalization, severe disease, and death in patients with COVID-19. ...

Bacteria contain symmetry in their DNA signals that enable them to be read either forwards or backwards, according to new findings at the University of Birmingham which challenge existing knowledge about gene transcription.

In all living organisms, DNA code is divided into sections which provide information about a specific process. These must be read before the information can be used. Cells identify the start of each section using 'signposts', which scientists first identified in the 1960s.

It has always been assumed that these signposts enable genetic sequences ...

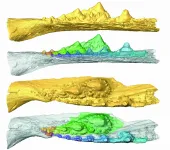

The origins of a pretty smile have long been sought in the fearsome jaws of living sharks which have been considered living fossils reflecting the ancestral condition for vertebrate tooth development and inference of its evolution. However, this view ignores real fossils which more accurately reflect the nature of ancient ancestors.

New research led by the University of Bristol and the Naturalis Biodiversity Center published in Nature Ecology and Evolution reveals that the dentitions of living shark relatives are entirely unrepresentative of the last shared ancestor of jawed vertebrates.

The study reveals ...

What The Study Did: This study estimates the association between Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccination and symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections among health care workers more than seven days after getting a second vaccine dose.

Authors: Ronen Ben-Ami, M.D., of the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center in Israel, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jama.2021.7152)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study ...

What The Study Did: This study describes an association between the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine and decreased risk of symptomatic and asymptomatic infections with SARS-CoV-2 in hospital employees.

Authors: Li Tang, Ph.D., of the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6564)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest ...

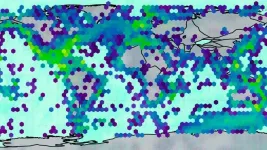

The bulging, equator-belted midsection of Earth currently teems with a greater diversity of life than anywhere else -- a biodiversity that generally wanes when moving from the tropics to the mid-latitudes and the mid-latitudes to the poles.

As well-accepted as that gradient is, though, ecologists continue to grapple with the primary reasons for it. New research from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Yale University and Stanford University suggests that temperature can largely explain why the greatest variety of aquatic life resides in the tropics -- but also why it has not ...

A key driver of patients' well-being and clinical trials for Parkinson's disease (PD) is the course the disease takes over time. However, nearly all that is known about the genetics of PD is related to susceptibility -- a person's risk for developing the disease in the future. A new study by investigators from Brigham and Women's Hospital published in Nature Genetics uncovers the genetic architecture of progression and prognosis, identifying five genetic locations (loci) associated with progression. The team also developed the first risk score for predicting ...

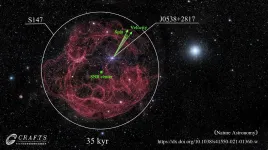

Pulsars - another name for fast-spinning neutron stars - originate from the imploded cores of massive dying stars through supernova explosion.

Now, more than 50 years after the discovery of pulsars and confirmation of their association with supernova explosions, the origin of the initial spin and velocity of pulsars is finally beginning to be understood.

Based on observations from the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical radio Telescope (FAST), Dr. YAO Jumei, member of a team led by Dr. LI Di from National Astronomical Observatories of Chinese Academy of Sciences (NAOC), found the first evidence for three-dimensional (3D) spin-velocity alignment in pulsars.

The study was published in Nature Astronomy on May 6. It also marks the beginning of in-depth pulsar research with FAST.

For decades, ...

While other medical systems across the country failed to maintain HIV screening volumes throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the University of Chicago Medicine maintained screening volumes by including universal HIV screening alongside COVID-19 testing in its busy emergency department, according to a new report published April 12 in JAMA Internal Medicine. Through targeted efforts to maintain infrastructure and enthusiasm for HIV screening, the number of HIV tests remained at pre-pandemic levels while the rate of acute HIV diagnoses actually increased.

Widespread screening to diagnose individuals newly infected with HIV is a key part of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) plan to ...

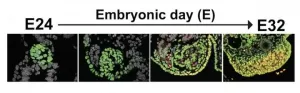

Early in human development, during the first trimester of gestation, a fetus may have XX or XY chromosomes that indicate its sex. Yet at this stage a mass of cells known as the bipotential gonad that ultimately develops into either ovaries or testes has yet to commit to its final destiny.

While researchers had studied the steps that go into the later stages of this process, little has been known about the precursors of the bipotential gonad. In a new study published in Cell Reports and co-led by Kotaro Sasaki of Penn's School of Veterinary Medicine, an international team lays ...