Timing is everything in new implant tech

Stimulators win top award at circuitry conference, could aid spinal cord, heart therapies

2021-05-10

(Press-News.org) HOUSTON - (May 10, 2021) - Implants that require a steady source of power but don't need wires are an idea whose time has come.

Now, for therapies that require multiple, coordinated stimulation implants, their timing has come as well.

Rice University engineers who developed implants for electrical stimulation in patients with spinal cord injuries have advanced their technique to power and program multisite biostimulators from a single transmitter.

A peer-reviewed paper about the advance by electrical and computer engineer Kaiyuan Yang and his colleagues at Rice's Brown School of Engineering won the best paper award at the IEEE's Custom Integrated Circuits Conference, held virtually in the last week of April.

The Rice lab's experiments showed an alternating magnetic field generated and controlled by a battery-powered transmitter outside the body, perhaps on a belt or harness, can deliver power and programming to two or more implants to at least 60 millimeters (2.3 inches) away.

The implants can be programmed with delays measured in microseconds. That could enable them to coordinate the triggering of multiple wireless pacemakers in separate chambers of a patient's heart, Yang said.

"We show it's possible to program the implants to stimulate in a coordinated pattern," he said. "We synchronize every device, like a symphony. That gives us a lot of degrees of freedom for stimulation treatments, whether it's for cardiac pacing or for a spinal cord."

The lab tested its tiny implants, each about the size and weight of a vitamin, on tissue samples, live hydra vulgaris and in rodents. The experiments proved that over at least a short distance, the devices were able to stimulate two separate hydra to contract and activate a fluorescent tag in response to electrical signals, and to trigger a response at controlled amplitudes along a rodent's sciatic nerve.

"There's a study on spinal cord regeneration that shows multisite stimulation in a certain pattern will help in the recovery of the neuro system," Yang said. "There is clinical research going on, but they're all using benchtop equipment. There are no implantable tools that can do this."

The lab's devices, called MagNI (for magnetoelectric neural implants) were introduced early last year as possible spinal cord stimulators that didn't require wires to power and program them. That means wire leads don't have to poke through the skin of the patient, a situation that would risk infection. The other alternative, as used in many battery-powered implants, is to replace them via surgery every few years.

INFORMATION:

Rice graduate student Zhanghao Yu is lead author of the paper. Co-authors are graduate students Joshua Chen, Yan He, Fatima Alrashdan and Amanda Singer, staff specialist Benjamin Avants and Jacob Robinson, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and bioengineering. Yang is an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering.

The National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering and National Science Foundation supported the research.

Read the paper at https://vlsi.rice.edu/upload/CICC_Yu_10_1.pdf.

This news release can be found online at https://news.rice.edu/2021/05/10/timing-is-everything-in-new-implant-tech/

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews.

Related materials:

Secure and Intelligent Micro-Systems Lab (Yang lab): https://vlsi.rice.edu

Robinson Lab: https://neuroengineering.rice.edu/faculty/jacob-robinson

Electrical and Computer Engineering: https://eceweb.rice.edu

George R. Brown School of Engineering: https://engineering.rice.edu

Video:

https://youtu.be/W0KbaK67PoM

A video demonstrates fluorescent signals and movement by a hydra vulgaris triggered by timed MagNi devices developed at Rice University. The wireless implants allow for multiple stimulators to be programmed and magnetically powered from a single transmitter outside the body. (Credit: Secure and Intelligent Micro-Systems Lab/Rice University)

Images for download:

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2021/05/0510_IMPLANT-2-WEB.jpg

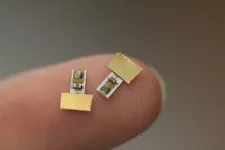

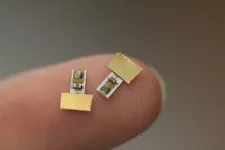

A new version of wireless implants developed at Rice University allows for multiple stimulators, as seen here, to be programmed and magnetically powered from a single transmitter outside the body. The implants could be used to treat spinal cord injuries or as pacemakers. (Credit: Secure and Intelligent Micro-Systems Lab/Rice University)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2021/05/0510_IMPLANT-1-WEB.jpg

Rice engineers have further developed neural implants that can be programmed and charged remotely with a magnetic field. The new version allows multiple implants to be charged and programmed from a single transmitter. From left, project leaders Kaiyuan Yang, Zhanghao Yu, Joshua Chen and Jacob Robinson. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation's top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 3,978 undergraduates and 3,192 graduate students, Rice's undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just under 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for lots of race/class interaction and No. 1 for quality of life by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger's Personal Finance.

Jeff Falk

713-348-6775

jfalk@rice.edu

Mike Williams

713-348-6728

mikewilliams@rice.edu

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-10

According to the International Whaling Commission, whale-watching tourism generates more than $2.5 billion a year. After the COVID-19 pandemic, this relatively safe outdoor activity is expected to rebound. Two new studies funded by a collaborative initiative between the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama and Arizona State University (ASU) show how science can contribute to whale watching practices that ensure the conservation and safety of whales and dolphins.

"The Smithsonian's role is to provide scientific advice to policy makers as they pioneer management strategies to promote whale conservation," said STRI marine biologist, Hector Guzmán, whose previous work led the International Maritime Organization to establish shipping corridors ...

2021-05-10

ATLANTA--Gestures--such as pointing or waving--go hand in hand with a child's first words, and twins lag behind single children in producing and using those gestures, two studies from Georgia State University psychology researchers show.

Twins produce fewer gestures and gesture to fewer objects than other children, said principal researcher Seyda Ozcaliskan, an associate professor in the Department of Psychology. Language use also lags for twins, and language--but not gesture--is also affected by sex, with girls performing better than boys, Ozcaliskan said.

"The implications are fascinating," said Ozcaliskan. ...

2021-05-10

MISSOULA - University of Montana Professor Mark Hebblewhite has joined an international team of 92 scientists and conservationists to create the first-ever global atlas of ungulate (hoofed mammal) migrations.

Working in partnership with the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals, a U.N. treaty, the Global Initiative on Ungulate Migration (GIUM) launches May 7 with the publication of a commentary in Science titled " END ...

2021-05-10

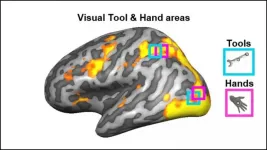

Visual brain areas involved in processing hands also encode information about the correct way to hold tools, according to new research published in JNeurosci.

Each part of the brain's visual system activates in response to a certain type of item -- whether it's faces, tools, objects, or hands. Scientists assumed the brain segregates visual information in this way to optimize motor actions with tools. Yet most studies investigating the brain mechanisms for tool grasping used images of tools or hands, and no actual hand movements were performed.

Knights et al. used fMRI to measure the brain activity of participants as they grasped 3D-printed kitchen tools (spoon, knife, and pizza cutter) and similar-sized non-tools. ...

2021-05-10

Researchers at the University of East Anglia have made an astonishing discovery about how our brains control our hands.

They used MRI data to study which parts of the brain are used when we handle tools, such as a knives.

They read out the signal from certain brain regions and tried to distinguish when participants handled tools appropriately for use.

Humans have used tools for millions of years, but this research is the first to show that actions such grasping a knife by its handle for cutting are represented by brain areas that also represent images of human hands, our primary 'tool' for interacting with the world.

The research ...

2021-05-10

Imaging technology has come a long way since the beginning of photography in the mid-19th century. Now, many state-of-the-art cameras for demanding applications rely on mechanisms that are considerably different from those in consumer-oriented devices. One of these cameras employs what is known as "single-photon imaging," which can produce vastly superior results in dark conditions and fast dynamic scenes. But how does single-photon imaging differ from conventional imaging?

When taking a picture with a regular CMOS camera, like the ones on smartphones, ...

2021-05-10

Peptides " short strings of amino acids" play a vital role in health and industry with a huge range of medical uses including in antibiotics, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer drugs. They are also used in the cosmetics industry and for enhancing athletic performance. Altering the structure of natural peptides to produce improved compounds is therefore of great interest to scientists and industry. But how the machineries that produce these peptides work still isn't clearly understood.

Associate Professor Max Cryle from Monash University's Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI) has revealed a key aspect of peptide machinery in a paper published in Nature Communications today that provides a key to the "Holy Grail" of re-engineering peptides..

The findings will advance his lab's work into ...

2021-05-10

A new study from the Harvard GenderSci Lab in the journal Human Fertility, "The Future of Sperm: A Biovariability Framework for Understanding Global Sperm Count Trends" questions the panic over apparent trends of declining human sperm count.

Recent studies have claimed that sperm counts among men globally, and especially from "Western" countries, are in decline, leading to apocalyptic claims about the possible extinction of the human species.

But the Harvard paper, by Marion Boulicault, Sarah S. Richardson, and colleagues, reanalyzes claims of precipitous human sperm declines, re-evaluating evidence presented in the widely-cited 2017 meta-analysis by Hagai Levine, Shanna ...

2021-05-10

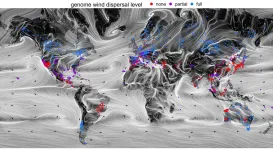

Berkeley -- Forests' ability to survive and adapt to the disruptions wrought by climate change may depend, in part, on the eddies and swirls of global wind currents, suggests a new study by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley.

Unlike animals, the trees that make up our planet's forests can't uproot and find new terrain if conditions get tough. Instead, many trees produce seeds and pollen that are designed to be carried away by the wind, an adaptation that helps them colonize new territories and maximize how far they can spread their genes.

The ...

2021-05-10

New research demonstrates that African and Asian leopards are more genetically differentiated from one another than polar bears and brown bears. Indeed, leopards are so different that they ought to be treated as two separate species, according to a team of researchers, among them, scientists from the University of Copenhagen. This new knowledge has important implications for better conserving this big and beautiful, yet widely endangered cat.

No one has any doubts about polar bears and brown bears being distinct species. Leopards, on the other hand, are considered one and the same, a single species, whether of African or Asian ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Timing is everything in new implant tech

Stimulators win top award at circuitry conference, could aid spinal cord, heart therapies