INFORMATION:

UEA team reads minds to understand human tool use

2021-05-10

(Press-News.org) Researchers at the University of East Anglia have made an astonishing discovery about how our brains control our hands.

They used MRI data to study which parts of the brain are used when we handle tools, such as a knives.

They read out the signal from certain brain regions and tried to distinguish when participants handled tools appropriately for use.

Humans have used tools for millions of years, but this research is the first to show that actions such grasping a knife by its handle for cutting are represented by brain areas that also represent images of human hands, our primary 'tool' for interacting with the world.

The research could pave the way for the development of next-generation neuroprosthetics - prosthetic limbs that tap into the brain's control centre, and help rehabilitate people who have lost function in their limbs due to brain injury.

The study was led by UEA and carried out at the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital.

Lead researcher Dr Stephanie Rossit, from UEA's School of Psychology, said: "The emergence of handheld tools marks the beginning of a major discontinuity between humans and our closest primate relatives and is considered a defining feature of our species. Our findings could shed light on the regions of the brain that specifically evolved in the humans."

"We knew that seeing images of tools activates a different region of the brain to when we see other kinds of objects, for example a chair.

"Until now it was assumed that the brain segregates visual information in this way to optimise processing of actions associated with tools. But how the human brain controls our hands to correctly grasp 3D objects such as tools was not well understood.

"We wanted to test whether the human brain automatically processes 3D objects in terms of how we grasp them for use. And we particularly wanted to find out whether we could use signals from specific parts of the brain to distinguish whether people were handling tools correctly - for example grasping a knife by the handle rather than the blade."

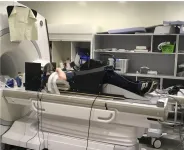

The team used an MRI scanner to collect brain imaging data while participants interacted with 3D objects.

Dr Rossit said: "This was really challenging because the space inside the scanner is really small and the participants need to stay really still.

"So we used a one-of-a-kind 'real action' set-up for presenting 3D tools and other objects.

"Our participants lay in the dark, on a custom-built bed with a revolving table mounted above their waist, so that we could show them 3D objects and they could grasp them.

"We designed and 3D-printed everyday kitchen tools from non-magnetic materials so that they would be safe in the MRI such as a plastic knife, pizza cutter and a spoon as well as another group of 3D-printed bars to represent items that were not tools, which we used as control objects."

Dr Ethan Knights, who was a PhD student with Dr Rossit, coordinated the data collection and scanned the brains of 20 volunteers at the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital. In the first session, participants were asked to grasp the 3D tool and 3D bars correctly or incorrectly using the bespoke 'real action' set-up.

The same participants returned to the scanner for a second session in which they simply looked at pictures of tools and hands.

Dr Fraser Smith, also from UEA's School of Psychology, said: "We studied brain activity when participants viewed pictures of tools and hands to identify which parts of the brain where the brain hand picture is represented.

"We then used state of the art machine learning to see if we could predict whether people actually grasped a tool by its handle or not. This is really important because knowing not to grasp an object, like a knife, by its blade, is critical to successful tool-use.

Dr Rossit said: "In contrast to what most scientists thought, we were able to predict whether a tool was grasped correctly from the signals of brain areas that respond to the sight of pictures of hands and not from visual areas that respond to the sight of pictures of tools.

"Importantly the signals from the visual hand areas could only be used to predict hand actions with tools but could not predict matched actions with the control 3D bar objects.

"This suggests that the visual hand areas are specially tuned for actions with tools.

"Our discovery changes our fundamental understanding of how the brain controls our hands and could have important implications for health and society.

"For example, it could help develop better devices or rehabilitation for people who have lost function in their limbs due to brain injury. And it could even allow people without limbs to control prosthetics with their minds.

"The potential for brain-driven interfaces and prosthetics is very exciting," she added.

'Hand-selective visual regions represent how to grasp 3D tools: brain decoding during real actions' is published in the Journal of Neuroscience on May 10, 2021. The study was funded by the BIAL Foundation.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

'Unmaking' a move: Correcting motion blur in single-photon images

2021-05-10

Imaging technology has come a long way since the beginning of photography in the mid-19th century. Now, many state-of-the-art cameras for demanding applications rely on mechanisms that are considerably different from those in consumer-oriented devices. One of these cameras employs what is known as "single-photon imaging," which can produce vastly superior results in dark conditions and fast dynamic scenes. But how does single-photon imaging differ from conventional imaging?

When taking a picture with a regular CMOS camera, like the ones on smartphones, ...

Monash study may help boost peptide design

2021-05-10

Peptides " short strings of amino acids" play a vital role in health and industry with a huge range of medical uses including in antibiotics, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer drugs. They are also used in the cosmetics industry and for enhancing athletic performance. Altering the structure of natural peptides to produce improved compounds is therefore of great interest to scientists and industry. But how the machineries that produce these peptides work still isn't clearly understood.

Associate Professor Max Cryle from Monash University's Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI) has revealed a key aspect of peptide machinery in a paper published in Nature Communications today that provides a key to the "Holy Grail" of re-engineering peptides..

The findings will advance his lab's work into ...

Should we panic over declining sperm counts? Harvard researchers say not so fast

2021-05-10

A new study from the Harvard GenderSci Lab in the journal Human Fertility, "The Future of Sperm: A Biovariability Framework for Understanding Global Sperm Count Trends" questions the panic over apparent trends of declining human sperm count.

Recent studies have claimed that sperm counts among men globally, and especially from "Western" countries, are in decline, leading to apocalyptic claims about the possible extinction of the human species.

But the Harvard paper, by Marion Boulicault, Sarah S. Richardson, and colleagues, reanalyzes claims of precipitous human sperm declines, re-evaluating evidence presented in the widely-cited 2017 meta-analysis by Hagai Levine, Shanna ...

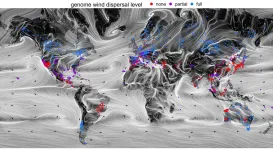

As global climate shifts, forests' futures may be caught in the wind

2021-05-10

Berkeley -- Forests' ability to survive and adapt to the disruptions wrought by climate change may depend, in part, on the eddies and swirls of global wind currents, suggests a new study by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley.

Unlike animals, the trees that make up our planet's forests can't uproot and find new terrain if conditions get tough. Instead, many trees produce seeds and pollen that are designed to be carried away by the wind, an adaptation that helps them colonize new territories and maximize how far they can spread their genes.

The ...

Differences between leopards are greater than between brown bears and polar bears

2021-05-10

New research demonstrates that African and Asian leopards are more genetically differentiated from one another than polar bears and brown bears. Indeed, leopards are so different that they ought to be treated as two separate species, according to a team of researchers, among them, scientists from the University of Copenhagen. This new knowledge has important implications for better conserving this big and beautiful, yet widely endangered cat.

No one has any doubts about polar bears and brown bears being distinct species. Leopards, on the other hand, are considered one and the same, a single species, whether of African or Asian ...

Intense light may hold answer to dilemma over heart treatment

2021-05-10

AURORA, Colo. (May 10, 2021) - Looking to safely block a gene linked to factors known to cause heart disease, scientists at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus may have found a new tool - light.

The study, published Monday in the journal Trends in Molecular Medicine, may solve a medical dilemma that has baffled scientists for years.

The gene, ANGPTL4, regulates fatty lipids in plasma. Scientists have found that people with lower levels of it also have reduced triglycerides and lipids, meaning less risk for cardiovascular disease.

But blocking the gene using antibodies triggered dangerous inflammation in mice. Complicating things further, the gene can also be beneficial in reducing the risk of myocardial ...

Bacteria do not colonize the gut before birth, says collaborative study

2021-05-10

Hamilton, ON (May 10, 2021) - It is well known that each person's gut bacteria is vital for digestion and overall health, but when does that gut microbiome start?

New research led by scientists from McMaster University and Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin in Germany has found it happens during and after birth, and not before.

McMaster researchers Deborah Sloboda and Katherine Kennedy examined prenatal stool (meconium) samples collected from 20 babies during breech Cesarean delivery.

"The key takeaway from our study is we are not colonized before birth. Rather, our relationship with our gut bacteria emerges ...

Growing sweet corn at higher densities doesn't increase root lodging risk

2021-05-10

URBANA, Ill. - Sweet corn growers and processors could be bringing in more profits by exploiting natural density tolerance traits in certain hybrids. That's according to 2019 research from USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and University of Illinois scientists.

But since root systems get smaller as plant density goes up, some in the industry are concerned about the risk of root lodging with greater sweet corn density. New research says those concerns are unjustified.

"Root lodging can certainly be a problem for sweet corn, but not because of plant density. What really matters is the specific hybrid and the environment, those major rainfall and wind events that set up conditions for root structural failure," says ...

Long-lasting medications may improve treatment satisfaction for opioid use disorder

2021-05-10

WHAT: A commentary from leaders at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, part of the NIH, discusses a new study showing that an extended-release injection of buprenorphine, a medication used to treat opioid use disorder, was preferred by patients compared to immediate-release buprenorphine, which must be taken orally every day. Extended-release formulations of medications used to treat opioid use disorder may be a valuable tool to address the current opioid addiction crisis and reduce its associated mortality. The study and the accompanying commentary were published May 10, 2021 in JAMA Network Open.

It is well established that medications used to treat ...

Scientists find mechanism that eliminates senescent cells

2021-05-10

Scientists at UC San Francisco are learning how immune cells naturally clear the body of defunct - or senescent - cells that contribute to aging and many chronic diseases. Understanding this process may open new ways of treating age-related chronic diseases with immunotherapy.

In a healthy state, these immune cells - known as invariant Natural Killer T (iNKT) cells - function as a surveillance system, eliminating cells the body senses as foreign, including senescent cells, which have irreparable DNA damage. But the iNKT cells become less active with age and other factors like obesity that contribute to chronic disease.

Finding ways to stimulate this natural surveillance system offers an alternative to senolytic ...