(Press-News.org) Berkeley -- Forests' ability to survive and adapt to the disruptions wrought by climate change may depend, in part, on the eddies and swirls of global wind currents, suggests a new study by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley.

Unlike animals, the trees that make up our planet's forests can't uproot and find new terrain if conditions get tough. Instead, many trees produce seeds and pollen that are designed to be carried away by the wind, an adaptation that helps them colonize new territories and maximize how far they can spread their genes.

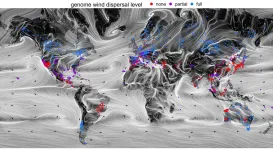

The new study compared global wind patterns with previously published genetic data of nearly 100 tree and shrub species collected from forests around the world, finding significant correlations between wind speed and direction and genetic diversity throughout our planet's forests. The findings are the first to show that wind may not only influence the spread of an individual tree or species' genes, but it can also help shape genetic diversity and direct the flow of gene variants across entire forests and landscapes.

Understanding how genetic variants move throughout a species range will become increasingly important as climate change alters the conditions of local habitats, the researchers say.

"How trees move and how plants move, in general, is a big area of uncertainty in plant ecology because it's hard to study plant movements directly -- they happen as a result small, rare movements of seeds and pollen," said study lead author Matthew Kling, a postdoctoral researcher in integrative biology at UC Berkeley. "However, to predict how species distributions, and plant ecology, in general, will respond to climate change, we need to understand how these species are going to be able to move long distances to track the movement of natural resources and climate conditions over time."

While animals, birds and insects can also disperse pollen and seeds, wind's strong directionality makes it particularly important for understanding how different tree species will respond to climate change, said study senior author David Ackerly, a professor and dean of UC Berkeley's Rausser College of Natural Resources.

"As the world warms, many plants and animals will need to move to places with suitable habitat in the future to survive," Ackerly said. "Wind dispersal has a particularly interesting connection to climate change because wind can either push the genes or organisms in the right direction, toward more suitable habitat, or in the opposite direction. It may be the only terrestrial dispersal vector that can be aligned with or against the direction of climate change."

Any way the wind blows

Despite the fickle nature of daily weather conditions, large-scale global wind patterns are largely determined by Earth's shape, rotation and the locations of the continents, and are believed to be relatively stable over millennial time-scales. These wind patterns are also unlikely to be dramatically altered by climate change, Kling said.

To examine whether these global prevailing winds have shaped the genetic diversity of modern-day forests, Kling compared current planetary wind models -- compiled from 30 years of global wind data -- with genetic data from 72 publications covering 97 tree and shrub species and 1,940 plant populations worldwide.

Kling's analysis revealed three key ways that global wind patterns are shaping forests' genetic diversity. First, tree populations that are connected by stronger wind currents tend to be more genetically similar than tree populations that are not as connected. Second, tree populations that are more downwind, or farther in the direction that the wind blows, tend to have more genetic diversity in general. Finally, genetic variants are more likely to disperse in the direction of the wind.

Though these patterns can only be statistically validated by looking at many populations of trees throughout the world, they can sometimes be evident when examining the genetic diversity of a single tree species across its habitat range, Kling said.

For example, the island scrub oak, or Quercus pacifica, is native to the Channel Islands in Southern California, where prevailing winds tend to blow to the southeast. Kling's analysis showed that scrub oak populations on islands that are connected by higher wind speeds are more genetically similar to each other. Genetic variants also appear to have dispersed more frequently to the islands in the southward and eastward directions than the reverse, leading to greater genetic diversity to the south and east.

Kling hopes that recognizing these patterns will help conservationists and ecologists better understand how well tree and plant species in different regions of the globe will adapt to a warming world.

"Populations in different portions of a species range have evolved over time to be well-adapted to the climate in that specific part of the range, and as climate changes, they can become out of sync with those conditions," Kling said. "Understanding how quickly genetic variants from elsewhere in the species range can get where they are needed is important for understanding how quickly the species will respond to climate change, and how vulnerable, versus resilient, a given population might be."

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship.

New research demonstrates that African and Asian leopards are more genetically differentiated from one another than polar bears and brown bears. Indeed, leopards are so different that they ought to be treated as two separate species, according to a team of researchers, among them, scientists from the University of Copenhagen. This new knowledge has important implications for better conserving this big and beautiful, yet widely endangered cat.

No one has any doubts about polar bears and brown bears being distinct species. Leopards, on the other hand, are considered one and the same, a single species, whether of African or Asian ...

AURORA, Colo. (May 10, 2021) - Looking to safely block a gene linked to factors known to cause heart disease, scientists at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus may have found a new tool - light.

The study, published Monday in the journal Trends in Molecular Medicine, may solve a medical dilemma that has baffled scientists for years.

The gene, ANGPTL4, regulates fatty lipids in plasma. Scientists have found that people with lower levels of it also have reduced triglycerides and lipids, meaning less risk for cardiovascular disease.

But blocking the gene using antibodies triggered dangerous inflammation in mice. Complicating things further, the gene can also be beneficial in reducing the risk of myocardial ...

Hamilton, ON (May 10, 2021) - It is well known that each person's gut bacteria is vital for digestion and overall health, but when does that gut microbiome start?

New research led by scientists from McMaster University and Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin in Germany has found it happens during and after birth, and not before.

McMaster researchers Deborah Sloboda and Katherine Kennedy examined prenatal stool (meconium) samples collected from 20 babies during breech Cesarean delivery.

"The key takeaway from our study is we are not colonized before birth. Rather, our relationship with our gut bacteria emerges ...

URBANA, Ill. - Sweet corn growers and processors could be bringing in more profits by exploiting natural density tolerance traits in certain hybrids. That's according to 2019 research from USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and University of Illinois scientists.

But since root systems get smaller as plant density goes up, some in the industry are concerned about the risk of root lodging with greater sweet corn density. New research says those concerns are unjustified.

"Root lodging can certainly be a problem for sweet corn, but not because of plant density. What really matters is the specific hybrid and the environment, those major rainfall and wind events that set up conditions for root structural failure," says ...

WHAT: A commentary from leaders at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, part of the NIH, discusses a new study showing that an extended-release injection of buprenorphine, a medication used to treat opioid use disorder, was preferred by patients compared to immediate-release buprenorphine, which must be taken orally every day. Extended-release formulations of medications used to treat opioid use disorder may be a valuable tool to address the current opioid addiction crisis and reduce its associated mortality. The study and the accompanying commentary were published May 10, 2021 in JAMA Network Open.

It is well established that medications used to treat ...

Scientists at UC San Francisco are learning how immune cells naturally clear the body of defunct - or senescent - cells that contribute to aging and many chronic diseases. Understanding this process may open new ways of treating age-related chronic diseases with immunotherapy.

In a healthy state, these immune cells - known as invariant Natural Killer T (iNKT) cells - function as a surveillance system, eliminating cells the body senses as foreign, including senescent cells, which have irreparable DNA damage. But the iNKT cells become less active with age and other factors like obesity that contribute to chronic disease.

Finding ways to stimulate this natural surveillance system offers an alternative to senolytic ...

A new study in Current Biology from the Institute of Genomics of the University of Tartu, Estonia has shed light on the genetic prehistory of populations in modern day Italy through the analysis of ancient human individuals during the Chalcolithic/Bronze Age transition around 4,000 years ago. The genomic analysis of ancient samples enabled researchers from Estonia, Italy, and the UK to date the arrival of the Steppe-related ancestry component to 3,600 years ago in Central Italy, also finding changes in burial practice and kinship structure during this transition.

In the last years, the genetic history of ancient individuals has been extensively studied focusing on ...

Northwestern University researchers are building social bonds with beams of light.

For the first time ever, Northwestern engineers and neurobiologists have wirelessly programmed -- and then deprogrammed -- mice to socially interact with one another in real time. The advancement is thanks to a first-of-its-kind ultraminiature, wireless, battery-free and fully implantable device that uses light to activate neurons.

This study is the first optogenetics (a method for controlling neurons with light) paper exploring social interactions within groups of animals, which was previously impossible with current technologies.

The research will be published May 10 in the journal ...

There are billions of neurons in the human brain, and scientists want to know how they are connected. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Alle Davis and Maxine Harrison Professor of Neurosciences Anthony Zador, and colleagues Xiaoyin Chen and Yu-Chi Sun, published a new technique in Nature Neuroscience for figuring out connections using genetic tags. Their technique, called BARseq2, labels brain cells with short RNA sequences called "barcodes," allowing the researchers to trace thousands of brain circuits simultaneously.

Many brain mapping tools allow neuroscientists to examine a handful of individual neurons at a time, for example by injecting them with dye. Chen, a postdoc in Zador's lab, explains how their tool, BARseq, is different:

"The idea here is that instead ...

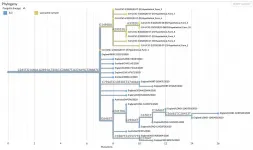

The COVID-19 pandemic has spurred genomic surveillance of viruses on an unprecedented scale, as scientists around the world use genome sequencing to track the spread of new variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The rapid accumulation of viral genome sequences presents new opportunities for tracing global and local transmission dynamics, but analyzing so much genomic data is challenging.

"There are now more than a million genome sequences for SARS-CoV-2. No one had anticipated that number when we started sequencing this virus," said Russ Corbett-Detig, assistant professor of biomolecular engineering at UC Santa Cruz.

The sheer number of coronavirus genome sequences and their rapid accumulation makes it hard to place new sequences on a "family ...