Scientists find mechanism that eliminates senescent cells

Discovery points to potential immune therapy for chronic disease and fibrosis

2021-05-10

(Press-News.org) Scientists at UC San Francisco are learning how immune cells naturally clear the body of defunct - or senescent - cells that contribute to aging and many chronic diseases. Understanding this process may open new ways of treating age-related chronic diseases with immunotherapy.

In a healthy state, these immune cells - known as invariant Natural Killer T (iNKT) cells - function as a surveillance system, eliminating cells the body senses as foreign, including senescent cells, which have irreparable DNA damage. But the iNKT cells become less active with age and other factors like obesity that contribute to chronic disease.

Finding ways to stimulate this natural surveillance system offers an alternative to senolytic therapies, which to date have been the primary approach to removing senescent cells. It could be a boon to a field that has struggled with how to systemically administer these senolytics without serious side effects.

The iNKT cells have two attributes that make them an especially appealing drug target. First, they all have the same receptor, which does not appear on any other cell in the body, so they can be primed without also activating other types of immune cells. Second, they operate within a natural negative feedback loop that returns them to a dormant state after a period of activity.

"Using iNKT-targeted therapy can piggyback on their exquisite, built-in specificity," said Anil Bhushan, PhD, a professor of medicine at UCSF in the Diabetes Center and senior author of the paper, which appears May 10, 2021, in Med.

The scientific team found they could remove senescent cells by using lipid antigens to activate iNKT cells. When they treated mice with diet-induced obesity, their blood glucose levels improved, while mice with lung fibrosis had fewer damaged cells, and they also lived longer.

Mallar Bhattacharya, MD, associate professor of medicine at UCSF who treats patients with lung disease and is an author of the paper, said the results presented for iNKT cells in a mouse model of lung fibrosis offer hope for a potentially fatal disease that often leads to lung transplants.

"I think this is a potential immune therapy for senescence and fibrosis," Bhattacharya said. "It's a fairly well tolerated therapy, and we just have to get around dosing and trials."

A diabetes researcher, Bhushan first started paying attention to iNKT cells when a previous study identified a link between iNKT cells and senescent pancreatic beta cells. Because senescent cells tend to accumulate in many tissues and correlate with disease, he surmised that activating iNKT cells could be used to treat a wide variety of diseases.

INFORMATION:

A biotech company that Bushan helped found, Deciduous Therapeutics, Inc., is planning to translate this early discovery to the clinic in the next few years.

Additional co-authors include Peter Thompson, Shivani Arora, Yao Wang, Aritra Bhattacharyya, Hara Apostolopoulou, Ram Naikawadi, Paul Wolters and Suneil Koliwad, all of UCSF; and Rachel Hatano and Ajit Shah of Deciduous.

The research was supported by the Larry L. Hillblom Foundation, the Diabetes Research Connection, the UCSF Sandler Asthma Basic Research Center, the UCSF Diabetes Center and NIH R01DK121794 and R01DK118099.

About UCSF: The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is exclusively focused on the health sciences and is dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. UCSF Health, which serves as UCSF's primary academic medical center, includes top-ranked specialty hospitals and other clinical programs, and has affiliations throughout the Bay Area. UCSF School of Medicine also has a regional campus in Fresno. Learn more at ucsf.edu, or see our Fact Sheet.

Follow UCSF END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-10

A new study in Current Biology from the Institute of Genomics of the University of Tartu, Estonia has shed light on the genetic prehistory of populations in modern day Italy through the analysis of ancient human individuals during the Chalcolithic/Bronze Age transition around 4,000 years ago. The genomic analysis of ancient samples enabled researchers from Estonia, Italy, and the UK to date the arrival of the Steppe-related ancestry component to 3,600 years ago in Central Italy, also finding changes in burial practice and kinship structure during this transition.

In the last years, the genetic history of ancient individuals has been extensively studied focusing on ...

2021-05-10

Northwestern University researchers are building social bonds with beams of light.

For the first time ever, Northwestern engineers and neurobiologists have wirelessly programmed -- and then deprogrammed -- mice to socially interact with one another in real time. The advancement is thanks to a first-of-its-kind ultraminiature, wireless, battery-free and fully implantable device that uses light to activate neurons.

This study is the first optogenetics (a method for controlling neurons with light) paper exploring social interactions within groups of animals, which was previously impossible with current technologies.

The research will be published May 10 in the journal ...

2021-05-10

There are billions of neurons in the human brain, and scientists want to know how they are connected. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Alle Davis and Maxine Harrison Professor of Neurosciences Anthony Zador, and colleagues Xiaoyin Chen and Yu-Chi Sun, published a new technique in Nature Neuroscience for figuring out connections using genetic tags. Their technique, called BARseq2, labels brain cells with short RNA sequences called "barcodes," allowing the researchers to trace thousands of brain circuits simultaneously.

Many brain mapping tools allow neuroscientists to examine a handful of individual neurons at a time, for example by injecting them with dye. Chen, a postdoc in Zador's lab, explains how their tool, BARseq, is different:

"The idea here is that instead ...

2021-05-10

The COVID-19 pandemic has spurred genomic surveillance of viruses on an unprecedented scale, as scientists around the world use genome sequencing to track the spread of new variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The rapid accumulation of viral genome sequences presents new opportunities for tracing global and local transmission dynamics, but analyzing so much genomic data is challenging.

"There are now more than a million genome sequences for SARS-CoV-2. No one had anticipated that number when we started sequencing this virus," said Russ Corbett-Detig, assistant professor of biomolecular engineering at UC Santa Cruz.

The sheer number of coronavirus genome sequences and their rapid accumulation makes it hard to place new sequences on a "family ...

2021-05-10

PHILADELPHIA-- New research performed in mice models at Penn Medicine shows, mechanistically, how the infant lung regenerates cells after injury differently than the adult lung, with alveolar type 1 (AT1) cells reprograming into alveolar type 2 (AT2) cells (two very different lung alveolar epithelial cells), promoting cell regeneration, rather than AT2 cells differentiating into AT1 cells, which is the most widely accepted mechanism in the adult lung. These study findings, published today in Cell Stem Cell, show that the long-held assumption that AT1 ...

2021-05-10

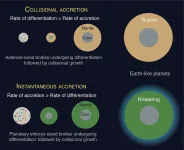

HOUSTON - (May 10, 2021) - The prospects for life on a given planet depend not only on where it forms but also how, according to Rice University scientists.

Planets like Earth that orbit within a solar system's Goldilocks zone, with conditions supporting liquid water and a rich atmosphere, are more likely to harbor life. As it turns out, how that planet came together also determines whether it captured and retained certain volatile elements and compounds, including nitrogen, carbon and water, that give rise to life.

In a study published in Nature Geoscience, Rice graduate student and lead author Damanveer Grewal and Professor Rajdeep Dasgupta show the competition between the time it takes for material to accrete into a protoplanet and the time the protoplanet ...

2021-05-10

ITHACA, N.Y. - Voyager 1 - one of two sibling NASA spacecraft launched 44 years ago and now the most distant human-made object in space - still works and zooms toward infinity.

The craft has long since zipped past the edge of the solar system through the heliopause - the solar system's border with interstellar space - into the interstellar medium. Now, its instruments have detected the constant drone of interstellar gas (plasma waves), according to Cornell University-led research published in Nature Astronomy.

Examining data slowly sent back from more than 14 billion miles away, Stella Koch Ocker, a Cornell doctoral student in astronomy, has uncovered the emission. "It's very faint and monotone, because ...

2021-05-10

Speech problems such as stammering or stuttering plague millions of people worldwide, including 3 million Americans. President Biden himself struggled with stuttering as a child and has largely overcome it with speech therapy. The cause of stuttering has long been a mystery, but researchers at Tufts University are beginning to unlock its causes and a strategy to develop potential treatments using a very curious model system - songbirds. In a study published today in Current Biology, the researchers were able to observe that a simple, reversible pharmacological treatment in zebra finches can stimulate rapid firing in a part of the brain that leads ...

2021-05-10

Numerous disease development processes are linked to epigenetic modulation. One protein involved in the process of modulation and identified as an important cancer marker is BRD4. A recent study by the research group of Giulio Superti-Furga, Principal Investigator and Scientific Director at the CeMM Research Center for Molecular Medicine of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, now shows that the supply of purines as well as the purine synthesis of a cell can influence BRD4 activity and thus play a role in the carcinogenesis process. The findings were published in Nature Metabolism.

Chromatin is a ...

2021-05-10

New Curtin University research has found a bias among scientists toward colourful and visually striking plants, means they are more likely to be chosen for scientific study and benefit from subsequent conservation efforts, regardless of their ecological importance.

Co-author John Curtin Distinguished Professor Kingsley Dixon from Curtin's School of Molecular and Life Sciences was part of an international team that looked for evidence of an aesthetic bias among scientists by analysing 113 plant species found in global biodiversity hotspot the Southwestern Alps and mentioned in 280 research papers published between 1975 and 2020.

Professor Dixon said the study tested whether there was a relationship between research focus on plant species and characteristics ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Scientists find mechanism that eliminates senescent cells

Discovery points to potential immune therapy for chronic disease and fibrosis