Bronze Age migrations changed societal organization and genomic landscape in Italy

2021-05-10

(Press-News.org) A new study in Current Biology from the Institute of Genomics of the University of Tartu, Estonia has shed light on the genetic prehistory of populations in modern day Italy through the analysis of ancient human individuals during the Chalcolithic/Bronze Age transition around 4,000 years ago. The genomic analysis of ancient samples enabled researchers from Estonia, Italy, and the UK to date the arrival of the Steppe-related ancestry component to 3,600 years ago in Central Italy, also finding changes in burial practice and kinship structure during this transition.

In the last years, the genetic history of ancient individuals has been extensively studied focusing on movements and settlements of humans in different areas of Eurasia. However, the genetic history of individuals from the Italian Peninsula during the Chalcolithic/Bronze Age transition, around 4,000 years ago, was still unexplored. Researchers from the Institute of Genomics of the University of Tartu in collaboration with universities in Italy and the UK have collected human remains from the Italian Peninsula and generated ancient genomes in the aDNA laboratory at the University of Tartu, Estonia.

"For the study, we extracted ancient DNA of 50 individuals from four archaeological sites located in Northeastern and Central Italy dated to Chalcolithic, Early Bronze Age, and Bronze Age. We were able to generate the first genome-wide shotgun data of ancient Italians dated to the Bronze Age period and study the arrival of the Steppe-related ancestry component in the Italian Peninsula. This genetic component, ultimately tracing its origin in the Pontic-Caspian Steppe, a steppeland located between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, and very common in Central and Northern Europe. It is also presented in the Bronze Age Italian individuals which we scrutinised and suggesting that populations in the South of the Alps experienced a similar evolution," said the lead author of the work Tina Saupe, from the Institute of Genomics.

"For the genetic analysis, we used a reference dataset including individuals from the Italian Peninsula, Sicily, and Sardinia dated from the Neolithic to the Iron Age. We decided to study the new genomes altogether with available data to have a deeper insight into the genetic changes and demography of this important transition, but also to understand its impact in the following centuries" added co-author Francesco Montinaro from the same institution and from the University of Bari, Italy. Researchers found that samples dated to the Neolithic and Chalcolithic from the Italian Peninsula are more similar to Early Neolithic farmers in Eastern Europe and Anatolian farmers than to farmers from Western Europe, which opens the possibility of different histories for the two Neolithic groups in Europe.

"Because of the geographical distribution of the archaeological sites of published and newly generated genomes, we were able to date the arrival of the Steppe-related ancestry component to at least ~4,000 years ago in Northern Italy and ~3,600 years ago in Central Italy. We did not find the component in individuals dated to the Neolithic and Chalcolithic, but in individuals dated to the Early Bronze Age and increasing through time in the individuals dated to the Bronze Age," pointed out by Luca Pagani, Associate Professor at the Institute of Genomics and University of Padova and co-senior author of this work.

"In addition, we were able to find a shift in burial practice correlated with the change of relatedness between the individuals in two of the sites, but we did not find any changes in the phenotypes of ancient Italians during the transition," said Christiana L. Scheib, the aDNA research group leader at the Institute of Genomics and corresponding author.

"It was remarkable to see how this project developed over time and how the interpretation of the results changed once samples from Central Italy were added thanks to the collaboration with the universities of Oxford (UK), Durham (UK), Groningen (Netherlands) and Rome "Tor Vergata" (Italy) "said Cristian Capelli (University of Parma), co-senior author of this study.

"These results of this study have shown that the genetic profile of ancient individuals from the Italian Peninsula changed with the movement and settlement of humans since the Neolithic. This knowledge enlightens us on our genetic origin and enables plans for further studies including a denser sampling of individuals dated to the Iron Age and Roman empire," concluded Scheib.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-10

Northwestern University researchers are building social bonds with beams of light.

For the first time ever, Northwestern engineers and neurobiologists have wirelessly programmed -- and then deprogrammed -- mice to socially interact with one another in real time. The advancement is thanks to a first-of-its-kind ultraminiature, wireless, battery-free and fully implantable device that uses light to activate neurons.

This study is the first optogenetics (a method for controlling neurons with light) paper exploring social interactions within groups of animals, which was previously impossible with current technologies.

The research will be published May 10 in the journal ...

2021-05-10

There are billions of neurons in the human brain, and scientists want to know how they are connected. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Alle Davis and Maxine Harrison Professor of Neurosciences Anthony Zador, and colleagues Xiaoyin Chen and Yu-Chi Sun, published a new technique in Nature Neuroscience for figuring out connections using genetic tags. Their technique, called BARseq2, labels brain cells with short RNA sequences called "barcodes," allowing the researchers to trace thousands of brain circuits simultaneously.

Many brain mapping tools allow neuroscientists to examine a handful of individual neurons at a time, for example by injecting them with dye. Chen, a postdoc in Zador's lab, explains how their tool, BARseq, is different:

"The idea here is that instead ...

2021-05-10

The COVID-19 pandemic has spurred genomic surveillance of viruses on an unprecedented scale, as scientists around the world use genome sequencing to track the spread of new variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The rapid accumulation of viral genome sequences presents new opportunities for tracing global and local transmission dynamics, but analyzing so much genomic data is challenging.

"There are now more than a million genome sequences for SARS-CoV-2. No one had anticipated that number when we started sequencing this virus," said Russ Corbett-Detig, assistant professor of biomolecular engineering at UC Santa Cruz.

The sheer number of coronavirus genome sequences and their rapid accumulation makes it hard to place new sequences on a "family ...

2021-05-10

PHILADELPHIA-- New research performed in mice models at Penn Medicine shows, mechanistically, how the infant lung regenerates cells after injury differently than the adult lung, with alveolar type 1 (AT1) cells reprograming into alveolar type 2 (AT2) cells (two very different lung alveolar epithelial cells), promoting cell regeneration, rather than AT2 cells differentiating into AT1 cells, which is the most widely accepted mechanism in the adult lung. These study findings, published today in Cell Stem Cell, show that the long-held assumption that AT1 ...

2021-05-10

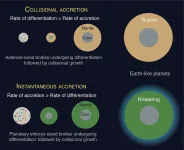

HOUSTON - (May 10, 2021) - The prospects for life on a given planet depend not only on where it forms but also how, according to Rice University scientists.

Planets like Earth that orbit within a solar system's Goldilocks zone, with conditions supporting liquid water and a rich atmosphere, are more likely to harbor life. As it turns out, how that planet came together also determines whether it captured and retained certain volatile elements and compounds, including nitrogen, carbon and water, that give rise to life.

In a study published in Nature Geoscience, Rice graduate student and lead author Damanveer Grewal and Professor Rajdeep Dasgupta show the competition between the time it takes for material to accrete into a protoplanet and the time the protoplanet ...

2021-05-10

ITHACA, N.Y. - Voyager 1 - one of two sibling NASA spacecraft launched 44 years ago and now the most distant human-made object in space - still works and zooms toward infinity.

The craft has long since zipped past the edge of the solar system through the heliopause - the solar system's border with interstellar space - into the interstellar medium. Now, its instruments have detected the constant drone of interstellar gas (plasma waves), according to Cornell University-led research published in Nature Astronomy.

Examining data slowly sent back from more than 14 billion miles away, Stella Koch Ocker, a Cornell doctoral student in astronomy, has uncovered the emission. "It's very faint and monotone, because ...

2021-05-10

Speech problems such as stammering or stuttering plague millions of people worldwide, including 3 million Americans. President Biden himself struggled with stuttering as a child and has largely overcome it with speech therapy. The cause of stuttering has long been a mystery, but researchers at Tufts University are beginning to unlock its causes and a strategy to develop potential treatments using a very curious model system - songbirds. In a study published today in Current Biology, the researchers were able to observe that a simple, reversible pharmacological treatment in zebra finches can stimulate rapid firing in a part of the brain that leads ...

2021-05-10

Numerous disease development processes are linked to epigenetic modulation. One protein involved in the process of modulation and identified as an important cancer marker is BRD4. A recent study by the research group of Giulio Superti-Furga, Principal Investigator and Scientific Director at the CeMM Research Center for Molecular Medicine of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, now shows that the supply of purines as well as the purine synthesis of a cell can influence BRD4 activity and thus play a role in the carcinogenesis process. The findings were published in Nature Metabolism.

Chromatin is a ...

2021-05-10

New Curtin University research has found a bias among scientists toward colourful and visually striking plants, means they are more likely to be chosen for scientific study and benefit from subsequent conservation efforts, regardless of their ecological importance.

Co-author John Curtin Distinguished Professor Kingsley Dixon from Curtin's School of Molecular and Life Sciences was part of an international team that looked for evidence of an aesthetic bias among scientists by analysing 113 plant species found in global biodiversity hotspot the Southwestern Alps and mentioned in 280 research papers published between 1975 and 2020.

Professor Dixon said the study tested whether there was a relationship between research focus on plant species and characteristics ...

2021-05-10

In cancer, a lot of biology goes awry: Genes mutate, molecular processes change dramatically, and cells proliferate uncontrollably to form entirely new tissues that we call tumors. Multiple things go wrong at different levels, and this complexity is partly what makes cancer so difficult to research and treat.

So it stands to reason that cancer researchers focus their attention where all cancers begin: the genome. If we can understand what happens at the level of DNA, then we can perhaps one day not just treat but even prevent cancers altogether.

This drive has led a ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Bronze Age migrations changed societal organization and genomic landscape in Italy