(Press-News.org) URBANA, Ill. - Sweet corn growers and processors could be bringing in more profits by exploiting natural density tolerance traits in certain hybrids. That's according to 2019 research from USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and University of Illinois scientists.

But since root systems get smaller as plant density goes up, some in the industry are concerned about the risk of root lodging with greater sweet corn density. New research says those concerns are unjustified.

"Root lodging can certainly be a problem for sweet corn, but not because of plant density. What really matters is the specific hybrid and the environment, those major rainfall and wind events that set up conditions for root structural failure," says Marty Williams, USDA-ARS ecologist, affiliate professor in the Department of Crop Sciences at Illinois, and author on a new study in Crop Science.

Williams and his co-authors used multiple approaches to understand the effects of planting density on root lodging in sweet corn. First, they planted sweet corn hybrid DMC 21-84 - a density-tolerant type that happens to be one of the most widely grown commercial hybrids - at five densities in experimental plots on U of I farms. When plants were at the tasseling stage, the researchers simulated a natural lodging event by flooding the field and knocking the corn over with a two-by-four.

"We mimicked a root lodging event with pure brute force," Williams says.

When corn is flattened in the process of root lodging, it can, depending on the growth stage, right itself through the plant's natural inclination to grow toward the light. As corn grows back upward from its repose, the base of the stem often carries a curved reminder of its lodging legacy, known as a gooseneck.

Williams and his team found most plants recovered to a near vertical position, albeit with a bit of goosenecking, within a few days of the artificial lodging event. They also measured yield metrics, and found no statistical difference in sweet corn yield between lodged and non-lodged plants.

But a two-by-four and brute force can't replace nature.

"Testing a crop's root lodging potential experimentally is inherently difficult. Simply put, a natural root lodging event may not happen in any given field experiment. As such, phenotyping crops for root lodging often employs the use of artificially created lodging events, like the ones we created," Williams says. "While artificially created root lodging events are helpful, used alone they often fail to capture a broad range of environments in which the crop is grown."

That's why the research team leveraged data from on-farm sweet corn trials across Illinois, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Between 2013 and 2017, the team evaluated economic optimum density for DMC 21-84 and 10 other hybrids under real-world farm management. And during that time, natural lodging events happened to occur in six of the 30 fields.

"We happened to take notes on lodging severity. It wasn't our specific focus at the time, but we figured, let's go ahead and score this and maybe we'll use it later. Turns out it was great that we collected root lodging data, because we were able to use it for this study," Williams says.

Those fortuitous notes showed that when sweet corn density increased from the current standard to the economic optimum density, typically a few thousand more plants per acre, there was absolutely no difference in the severity of lodging.

"What excited me about this work is that we combined an experiment where we created lodging artificially and looked at the response, and then we also tapped into this network of naturally occurring events. Together, they told a pretty convincing story," Williams says. "Simply put, root lodging potential should not keep us from using plant density tolerant hybrids and growing them at their correct density. I mean, there's always the possibility that root lodging could occur, but it's not going to be due to planting a few more plants."

INFORMATION:

The article, "Economic optimum plant density of sweet corn does not increase root lodging incidence," is published in Crop Science [DOI: 10.1002/csc2.20546]. Co-authors include Williams, Nicholas Hausman, Daljeet Dhaliwal, and Martin Bohn, Department of Crop Sciences, and Tony Grift, Department of Agricultural and Biological Engineering. Both departments are in the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences at the University of Illinois. Williams' primary affiliation is with the USDA-ARS Global Change and Photosynthesis Research Unit in Urbana, Illinois.

WHAT: A commentary from leaders at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, part of the NIH, discusses a new study showing that an extended-release injection of buprenorphine, a medication used to treat opioid use disorder, was preferred by patients compared to immediate-release buprenorphine, which must be taken orally every day. Extended-release formulations of medications used to treat opioid use disorder may be a valuable tool to address the current opioid addiction crisis and reduce its associated mortality. The study and the accompanying commentary were published May 10, 2021 in JAMA Network Open.

It is well established that medications used to treat ...

Scientists at UC San Francisco are learning how immune cells naturally clear the body of defunct - or senescent - cells that contribute to aging and many chronic diseases. Understanding this process may open new ways of treating age-related chronic diseases with immunotherapy.

In a healthy state, these immune cells - known as invariant Natural Killer T (iNKT) cells - function as a surveillance system, eliminating cells the body senses as foreign, including senescent cells, which have irreparable DNA damage. But the iNKT cells become less active with age and other factors like obesity that contribute to chronic disease.

Finding ways to stimulate this natural surveillance system offers an alternative to senolytic ...

A new study in Current Biology from the Institute of Genomics of the University of Tartu, Estonia has shed light on the genetic prehistory of populations in modern day Italy through the analysis of ancient human individuals during the Chalcolithic/Bronze Age transition around 4,000 years ago. The genomic analysis of ancient samples enabled researchers from Estonia, Italy, and the UK to date the arrival of the Steppe-related ancestry component to 3,600 years ago in Central Italy, also finding changes in burial practice and kinship structure during this transition.

In the last years, the genetic history of ancient individuals has been extensively studied focusing on ...

Northwestern University researchers are building social bonds with beams of light.

For the first time ever, Northwestern engineers and neurobiologists have wirelessly programmed -- and then deprogrammed -- mice to socially interact with one another in real time. The advancement is thanks to a first-of-its-kind ultraminiature, wireless, battery-free and fully implantable device that uses light to activate neurons.

This study is the first optogenetics (a method for controlling neurons with light) paper exploring social interactions within groups of animals, which was previously impossible with current technologies.

The research will be published May 10 in the journal ...

There are billions of neurons in the human brain, and scientists want to know how they are connected. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Alle Davis and Maxine Harrison Professor of Neurosciences Anthony Zador, and colleagues Xiaoyin Chen and Yu-Chi Sun, published a new technique in Nature Neuroscience for figuring out connections using genetic tags. Their technique, called BARseq2, labels brain cells with short RNA sequences called "barcodes," allowing the researchers to trace thousands of brain circuits simultaneously.

Many brain mapping tools allow neuroscientists to examine a handful of individual neurons at a time, for example by injecting them with dye. Chen, a postdoc in Zador's lab, explains how their tool, BARseq, is different:

"The idea here is that instead ...

The COVID-19 pandemic has spurred genomic surveillance of viruses on an unprecedented scale, as scientists around the world use genome sequencing to track the spread of new variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The rapid accumulation of viral genome sequences presents new opportunities for tracing global and local transmission dynamics, but analyzing so much genomic data is challenging.

"There are now more than a million genome sequences for SARS-CoV-2. No one had anticipated that number when we started sequencing this virus," said Russ Corbett-Detig, assistant professor of biomolecular engineering at UC Santa Cruz.

The sheer number of coronavirus genome sequences and their rapid accumulation makes it hard to place new sequences on a "family ...

PHILADELPHIA-- New research performed in mice models at Penn Medicine shows, mechanistically, how the infant lung regenerates cells after injury differently than the adult lung, with alveolar type 1 (AT1) cells reprograming into alveolar type 2 (AT2) cells (two very different lung alveolar epithelial cells), promoting cell regeneration, rather than AT2 cells differentiating into AT1 cells, which is the most widely accepted mechanism in the adult lung. These study findings, published today in Cell Stem Cell, show that the long-held assumption that AT1 ...

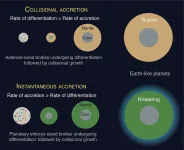

HOUSTON - (May 10, 2021) - The prospects for life on a given planet depend not only on where it forms but also how, according to Rice University scientists.

Planets like Earth that orbit within a solar system's Goldilocks zone, with conditions supporting liquid water and a rich atmosphere, are more likely to harbor life. As it turns out, how that planet came together also determines whether it captured and retained certain volatile elements and compounds, including nitrogen, carbon and water, that give rise to life.

In a study published in Nature Geoscience, Rice graduate student and lead author Damanveer Grewal and Professor Rajdeep Dasgupta show the competition between the time it takes for material to accrete into a protoplanet and the time the protoplanet ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - Voyager 1 - one of two sibling NASA spacecraft launched 44 years ago and now the most distant human-made object in space - still works and zooms toward infinity.

The craft has long since zipped past the edge of the solar system through the heliopause - the solar system's border with interstellar space - into the interstellar medium. Now, its instruments have detected the constant drone of interstellar gas (plasma waves), according to Cornell University-led research published in Nature Astronomy.

Examining data slowly sent back from more than 14 billion miles away, Stella Koch Ocker, a Cornell doctoral student in astronomy, has uncovered the emission. "It's very faint and monotone, because ...

Speech problems such as stammering or stuttering plague millions of people worldwide, including 3 million Americans. President Biden himself struggled with stuttering as a child and has largely overcome it with speech therapy. The cause of stuttering has long been a mystery, but researchers at Tufts University are beginning to unlock its causes and a strategy to develop potential treatments using a very curious model system - songbirds. In a study published today in Current Biology, the researchers were able to observe that a simple, reversible pharmacological treatment in zebra finches can stimulate rapid firing in a part of the brain that leads ...