Monash study may help boost peptide design

Finding the holy grail of re-engineering peptide design -- for better antibiotics and beyond

2021-05-10

(Press-News.org) Peptides " short strings of amino acids" play a vital role in health and industry with a huge range of medical uses including in antibiotics, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer drugs. They are also used in the cosmetics industry and for enhancing athletic performance. Altering the structure of natural peptides to produce improved compounds is therefore of great interest to scientists and industry. But how the machineries that produce these peptides work still isn't clearly understood.

Associate Professor Max Cryle from Monash University's Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI) has revealed a key aspect of peptide machinery in a paper published in Nature Communications today that provides a key to the "Holy Grail" of re-engineering peptides..

The findings will advance his lab's work into re-engineering glycopeptide antibiotics to counter the pressing global threat posed by antimicrobial resistance, and more broadly to improving the properties of peptides generally.

"Peptide synthesis machineries are often largely modular assembly lines, with each module comprised of different component parts. Changing what you make in these assembly lines, that is, peptides with new bioactivities, is a "holy grail" in re-design," Associate Professor Cryle said. "One of the things we tried to understand in this study was where the selectivity of these machineries come from - they're very selective for making one specific peptide and understanding where this specificity comes from is a bit of a mystery," he said.

"We were able to structurally characterise a part of such a machinery that generates the links within the peptides at a stage that hasn't been previously determined. What we showed is that these domains responsible for the linking of amino acids into peptides don't play a general role in selecting the amino acids during this process."

"This is good news from a re-engineering point of view because it means we don't need to concern ourselves with changing multiple pieces of the machinery to make single amino acid changes, we just need to focus on changing the building block that goes in and that's quite promising."

Associate Professor Cryle led a multidisciplinary team of scientists who enlisted a variety of techniques to model the peptide structures including using the Australian Synchrotron for X-ray crystallography along with chemical and biochemical techniques. He collaborated with groups in Canberra, Brisbane and Germany who helped with computational modelling and bioinformatics.

"Our ability to understand the enzymes that make natural peptides is key to our ability to produce improved ones to target issues like antimicrobial resistance," he said. "Now we can actually start to think about ways to change the machinery's acceptance of different building blocks and in this way we can make new peptides with improved antibacterial properties," he said.

In the future, a collaboration with Dr Evi Stegmann's group at the University of Tübingen in Germany will help translate the findings from a theoretical lab solution to eventually developing a commercial-scale production of new and improved antibiotics, he said.

INFORMATION:

Dr Thierry Izore, (previously at Monash BDI) from Medpace, and PhD student Candace Ho from The University of Warwick, UK, are equal first authors. The work is linked to Warwick University. Associate Professor Cryle is a member of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Innovations in Peptide and Protein Science.

Read the full paperNature Communications titled: Understanding condensation domain selectivity in non-ribosomal peptide biosynthesis: structural characterization of the acceptor bound state.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-10

A new study from the Harvard GenderSci Lab in the journal Human Fertility, "The Future of Sperm: A Biovariability Framework for Understanding Global Sperm Count Trends" questions the panic over apparent trends of declining human sperm count.

Recent studies have claimed that sperm counts among men globally, and especially from "Western" countries, are in decline, leading to apocalyptic claims about the possible extinction of the human species.

But the Harvard paper, by Marion Boulicault, Sarah S. Richardson, and colleagues, reanalyzes claims of precipitous human sperm declines, re-evaluating evidence presented in the widely-cited 2017 meta-analysis by Hagai Levine, Shanna ...

2021-05-10

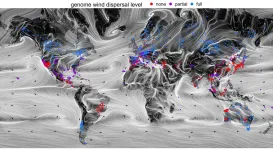

Berkeley -- Forests' ability to survive and adapt to the disruptions wrought by climate change may depend, in part, on the eddies and swirls of global wind currents, suggests a new study by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley.

Unlike animals, the trees that make up our planet's forests can't uproot and find new terrain if conditions get tough. Instead, many trees produce seeds and pollen that are designed to be carried away by the wind, an adaptation that helps them colonize new territories and maximize how far they can spread their genes.

The ...

2021-05-10

New research demonstrates that African and Asian leopards are more genetically differentiated from one another than polar bears and brown bears. Indeed, leopards are so different that they ought to be treated as two separate species, according to a team of researchers, among them, scientists from the University of Copenhagen. This new knowledge has important implications for better conserving this big and beautiful, yet widely endangered cat.

No one has any doubts about polar bears and brown bears being distinct species. Leopards, on the other hand, are considered one and the same, a single species, whether of African or Asian ...

2021-05-10

AURORA, Colo. (May 10, 2021) - Looking to safely block a gene linked to factors known to cause heart disease, scientists at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus may have found a new tool - light.

The study, published Monday in the journal Trends in Molecular Medicine, may solve a medical dilemma that has baffled scientists for years.

The gene, ANGPTL4, regulates fatty lipids in plasma. Scientists have found that people with lower levels of it also have reduced triglycerides and lipids, meaning less risk for cardiovascular disease.

But blocking the gene using antibodies triggered dangerous inflammation in mice. Complicating things further, the gene can also be beneficial in reducing the risk of myocardial ...

2021-05-10

Hamilton, ON (May 10, 2021) - It is well known that each person's gut bacteria is vital for digestion and overall health, but when does that gut microbiome start?

New research led by scientists from McMaster University and Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin in Germany has found it happens during and after birth, and not before.

McMaster researchers Deborah Sloboda and Katherine Kennedy examined prenatal stool (meconium) samples collected from 20 babies during breech Cesarean delivery.

"The key takeaway from our study is we are not colonized before birth. Rather, our relationship with our gut bacteria emerges ...

2021-05-10

URBANA, Ill. - Sweet corn growers and processors could be bringing in more profits by exploiting natural density tolerance traits in certain hybrids. That's according to 2019 research from USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and University of Illinois scientists.

But since root systems get smaller as plant density goes up, some in the industry are concerned about the risk of root lodging with greater sweet corn density. New research says those concerns are unjustified.

"Root lodging can certainly be a problem for sweet corn, but not because of plant density. What really matters is the specific hybrid and the environment, those major rainfall and wind events that set up conditions for root structural failure," says ...

2021-05-10

WHAT: A commentary from leaders at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, part of the NIH, discusses a new study showing that an extended-release injection of buprenorphine, a medication used to treat opioid use disorder, was preferred by patients compared to immediate-release buprenorphine, which must be taken orally every day. Extended-release formulations of medications used to treat opioid use disorder may be a valuable tool to address the current opioid addiction crisis and reduce its associated mortality. The study and the accompanying commentary were published May 10, 2021 in JAMA Network Open.

It is well established that medications used to treat ...

2021-05-10

Scientists at UC San Francisco are learning how immune cells naturally clear the body of defunct - or senescent - cells that contribute to aging and many chronic diseases. Understanding this process may open new ways of treating age-related chronic diseases with immunotherapy.

In a healthy state, these immune cells - known as invariant Natural Killer T (iNKT) cells - function as a surveillance system, eliminating cells the body senses as foreign, including senescent cells, which have irreparable DNA damage. But the iNKT cells become less active with age and other factors like obesity that contribute to chronic disease.

Finding ways to stimulate this natural surveillance system offers an alternative to senolytic ...

2021-05-10

A new study in Current Biology from the Institute of Genomics of the University of Tartu, Estonia has shed light on the genetic prehistory of populations in modern day Italy through the analysis of ancient human individuals during the Chalcolithic/Bronze Age transition around 4,000 years ago. The genomic analysis of ancient samples enabled researchers from Estonia, Italy, and the UK to date the arrival of the Steppe-related ancestry component to 3,600 years ago in Central Italy, also finding changes in burial practice and kinship structure during this transition.

In the last years, the genetic history of ancient individuals has been extensively studied focusing on ...

2021-05-10

Northwestern University researchers are building social bonds with beams of light.

For the first time ever, Northwestern engineers and neurobiologists have wirelessly programmed -- and then deprogrammed -- mice to socially interact with one another in real time. The advancement is thanks to a first-of-its-kind ultraminiature, wireless, battery-free and fully implantable device that uses light to activate neurons.

This study is the first optogenetics (a method for controlling neurons with light) paper exploring social interactions within groups of animals, which was previously impossible with current technologies.

The research will be published May 10 in the journal ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Monash study may help boost peptide design

Finding the holy grail of re-engineering peptide design -- for better antibiotics and beyond