Should we panic over declining sperm counts? Harvard researchers say not so fast

An alternative explanation of recent findings of declining sperm counts: normal, non-pathological variation

2021-05-10

(Press-News.org) A new study from the Harvard GenderSci Lab in the journal Human Fertility, "The Future of Sperm: A Biovariability Framework for Understanding Global Sperm Count Trends" questions the panic over apparent trends of declining human sperm count.

Recent studies have claimed that sperm counts among men globally, and especially from "Western" countries, are in decline, leading to apocalyptic claims about the possible extinction of the human species.

But the Harvard paper, by Marion Boulicault, Sarah S. Richardson, and colleagues, reanalyzes claims of precipitous human sperm declines, re-evaluating evidence presented in the widely-cited 2017 meta-analysis by Hagai Levine, Shanna Swan, and colleagues.

Richardson: "The extraordinary biological claims of the meta-analysis of sperm count trends and the public attention it continues to garner raised questions for the GenderSci Lab, which specializes in analyzing bias and hype in the sciences of sex, gender, and reproduction and in the intersectional study of race, gender, and science."

Boulicault et al. propose an alternative explanation of sperm count trends in human populations: That sperm count varies within a wide range, much of which can be considered non-pathological and species-typical, and that above a critical threshold, more is not necessarily an indicator of better health or higher probability of fertility relative to less. The authors term this the Sperm Count Biovariability hypothesis.

The paper argues that a biovariability framework better supports critically important research on factors affecting the reproductive health of all men. Lead author Boulicault: "By proposing an alternative approach to sperm count data, we aim to contribute to the burgeoning discussion among reproductive health scientists and other researchers and clinicians about men's health."

Among the reasons to consider alternative interpretations of sperm count patterns than that of precipitous and fertility-threatening declines in men's sperm counts is the life of such theories in Alt-Right, white supremacist, and men's rights discourse. These groups have used Levine and Swan's research to argue that the fertility and health of men in whiter nations are in imminent danger, often linking the danger to the perceived increase in ethnic and racial diversity and to the influence of feminist and anti-racist social movements.

The Harvard researchers argue that claims of recent and impending dramatic declines in human sperm counts are based on a number of scientifically and ethically problematic assumptions:

* Claims about precipitous sperm decline assume that sperm counts in Anglophone developed nations of the 1970s constitute the species optimum.

* Declining sperm counts do not predict declining fertility. The assumption that male fertility scales proportionately with sperm count is unsupported by any available evidence.

* The proposed causal mechanism for lower sperm counts of exposure to environmental endocrine disrupting chemicals is not supported by the geographical and historical patterns of average population sperm counts.

* The use of two categories labeled "Western" and "Other" in analyzing sperm counts, as seen in the major 2017 meta-analysis of sperm decline studies, is scientifically unsound and embeds unethical racist and colonial assumptions in the study design. These statistical aggregations obscure the diversity across rural and urban locations within nations, and disguise the fact that there is very limited data on individuals' sperm counts in countries Levine et al. categorized as "Other."

As the paper concludes, "Researchers must take care to weigh hypotheses against alternatives and consider the language and narrative frames in which they present their work. In addition to its explanatory virtues, we argue that biovariability offers a more promising framework than does "sperm decline" for attending to these imperatives."

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-10

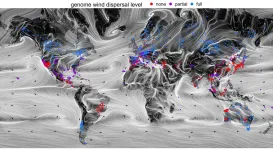

Berkeley -- Forests' ability to survive and adapt to the disruptions wrought by climate change may depend, in part, on the eddies and swirls of global wind currents, suggests a new study by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley.

Unlike animals, the trees that make up our planet's forests can't uproot and find new terrain if conditions get tough. Instead, many trees produce seeds and pollen that are designed to be carried away by the wind, an adaptation that helps them colonize new territories and maximize how far they can spread their genes.

The ...

2021-05-10

New research demonstrates that African and Asian leopards are more genetically differentiated from one another than polar bears and brown bears. Indeed, leopards are so different that they ought to be treated as two separate species, according to a team of researchers, among them, scientists from the University of Copenhagen. This new knowledge has important implications for better conserving this big and beautiful, yet widely endangered cat.

No one has any doubts about polar bears and brown bears being distinct species. Leopards, on the other hand, are considered one and the same, a single species, whether of African or Asian ...

2021-05-10

AURORA, Colo. (May 10, 2021) - Looking to safely block a gene linked to factors known to cause heart disease, scientists at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus may have found a new tool - light.

The study, published Monday in the journal Trends in Molecular Medicine, may solve a medical dilemma that has baffled scientists for years.

The gene, ANGPTL4, regulates fatty lipids in plasma. Scientists have found that people with lower levels of it also have reduced triglycerides and lipids, meaning less risk for cardiovascular disease.

But blocking the gene using antibodies triggered dangerous inflammation in mice. Complicating things further, the gene can also be beneficial in reducing the risk of myocardial ...

2021-05-10

Hamilton, ON (May 10, 2021) - It is well known that each person's gut bacteria is vital for digestion and overall health, but when does that gut microbiome start?

New research led by scientists from McMaster University and Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin in Germany has found it happens during and after birth, and not before.

McMaster researchers Deborah Sloboda and Katherine Kennedy examined prenatal stool (meconium) samples collected from 20 babies during breech Cesarean delivery.

"The key takeaway from our study is we are not colonized before birth. Rather, our relationship with our gut bacteria emerges ...

2021-05-10

URBANA, Ill. - Sweet corn growers and processors could be bringing in more profits by exploiting natural density tolerance traits in certain hybrids. That's according to 2019 research from USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and University of Illinois scientists.

But since root systems get smaller as plant density goes up, some in the industry are concerned about the risk of root lodging with greater sweet corn density. New research says those concerns are unjustified.

"Root lodging can certainly be a problem for sweet corn, but not because of plant density. What really matters is the specific hybrid and the environment, those major rainfall and wind events that set up conditions for root structural failure," says ...

2021-05-10

WHAT: A commentary from leaders at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, part of the NIH, discusses a new study showing that an extended-release injection of buprenorphine, a medication used to treat opioid use disorder, was preferred by patients compared to immediate-release buprenorphine, which must be taken orally every day. Extended-release formulations of medications used to treat opioid use disorder may be a valuable tool to address the current opioid addiction crisis and reduce its associated mortality. The study and the accompanying commentary were published May 10, 2021 in JAMA Network Open.

It is well established that medications used to treat ...

2021-05-10

Scientists at UC San Francisco are learning how immune cells naturally clear the body of defunct - or senescent - cells that contribute to aging and many chronic diseases. Understanding this process may open new ways of treating age-related chronic diseases with immunotherapy.

In a healthy state, these immune cells - known as invariant Natural Killer T (iNKT) cells - function as a surveillance system, eliminating cells the body senses as foreign, including senescent cells, which have irreparable DNA damage. But the iNKT cells become less active with age and other factors like obesity that contribute to chronic disease.

Finding ways to stimulate this natural surveillance system offers an alternative to senolytic ...

2021-05-10

A new study in Current Biology from the Institute of Genomics of the University of Tartu, Estonia has shed light on the genetic prehistory of populations in modern day Italy through the analysis of ancient human individuals during the Chalcolithic/Bronze Age transition around 4,000 years ago. The genomic analysis of ancient samples enabled researchers from Estonia, Italy, and the UK to date the arrival of the Steppe-related ancestry component to 3,600 years ago in Central Italy, also finding changes in burial practice and kinship structure during this transition.

In the last years, the genetic history of ancient individuals has been extensively studied focusing on ...

2021-05-10

Northwestern University researchers are building social bonds with beams of light.

For the first time ever, Northwestern engineers and neurobiologists have wirelessly programmed -- and then deprogrammed -- mice to socially interact with one another in real time. The advancement is thanks to a first-of-its-kind ultraminiature, wireless, battery-free and fully implantable device that uses light to activate neurons.

This study is the first optogenetics (a method for controlling neurons with light) paper exploring social interactions within groups of animals, which was previously impossible with current technologies.

The research will be published May 10 in the journal ...

2021-05-10

There are billions of neurons in the human brain, and scientists want to know how they are connected. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Alle Davis and Maxine Harrison Professor of Neurosciences Anthony Zador, and colleagues Xiaoyin Chen and Yu-Chi Sun, published a new technique in Nature Neuroscience for figuring out connections using genetic tags. Their technique, called BARseq2, labels brain cells with short RNA sequences called "barcodes," allowing the researchers to trace thousands of brain circuits simultaneously.

Many brain mapping tools allow neuroscientists to examine a handful of individual neurons at a time, for example by injecting them with dye. Chen, a postdoc in Zador's lab, explains how their tool, BARseq, is different:

"The idea here is that instead ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Should we panic over declining sperm counts? Harvard researchers say not so fast

An alternative explanation of recent findings of declining sperm counts: normal, non-pathological variation