'Unmaking' a move: Correcting motion blur in single-photon images

Researchers develop innovative deblurring method that works even for images with multiple objects moving independently

2021-05-10

(Press-News.org) Imaging technology has come a long way since the beginning of photography in the mid-19th century. Now, many state-of-the-art cameras for demanding applications rely on mechanisms that are considerably different from those in consumer-oriented devices. One of these cameras employs what is known as "single-photon imaging," which can produce vastly superior results in dark conditions and fast dynamic scenes. But how does single-photon imaging differ from conventional imaging?

When taking a picture with a regular CMOS camera, like the ones on smartphones, the camera sensor is open to a large influx of photons during a predefined exposure time. Each pixel in the sensor grid outputs an analog value that depends on the number of photons that hit that pixel during exposure. However, this type of imaging has few ways to deal with moving objects; the movement of the object has to be much slower than the exposure time to avoid blurring. In contrast, single-photon cameras capture a rapid burst of consecutive frames with very short individual exposure times. These frames are binary--a grid of 1s and 0s that respectively indicate whether one photon arrived at each pixel or not during exposure. To reconstruct an actual picture from these binary frames (or bit planes), many of them have to be processed into a single non-binary image. This can be achieved by assigning different levels of brightness to all the pixels in the grid, depending on how many of the bit planes had a "1" for each pixel.

Besides its higher speed, the completely digital nature of single-photon imaging allows for designing clever image reconstruction algorithms that can make up for technical limitations or difficult scenarios. At Tokyo University of Science, Japan, Professor Takayuki Hamamoto has been leading a research team focused on taking the capabilities of single-photon imaging further. In the latest study by Prof. Hamamoto and his team, which was published in IEEE Access, they developed a highly effective algorithm to fix the blurring caused by motion in the imaged objects, as well as common blurring of the entire image such as that caused by the shaking of the camera.

Their approach addresses many limitations of existing deblurring techniques for single-photon imaging, which produce low-quality pictures when multiple objects in the scene are moving at different speeds and dynamically overlapping each other. Instead of adjusting the entire image according to the estimated motion of a single object or on the basis of spatial regions where the object is considered to be moving, the proposed method employs a more versatile strategy.

First, a motion estimation algorithm tracks the movement of individual pixels through statistical evaluations on how bit values change over time (over different bit planes). In this way, as demonstrated experimentally by the researchers, the motion of individual objects can be accurately estimated. "Our tests show that the proposed motion estimation technique produced results with errors of less than one pixel, even in dark conditions with few incident photons," remarks Prof. Hamamoto.

The team then developed a deblurring algorithm that uses the results of the motion estimation step. This second algorithm groups pixels with a similar motion together, thereby identifying in each bit plane separate objects moving at different speeds. This allows for deblurring each region of the image independently according to the motions of objects that pass through it. Using simulations, the researchers showed that their strategy produced very crisp and high-quality images, even in low-light dynamic scenes crowded with objects coursing at disparate velocities.

Overall, the results of this study aptly showcase how greatly single-photon imaging can be improved if one gets down to developing effective image processing techniques. "Methods for obtaining crisp images in photon-limited situations would be useful in several fields, including medicine, security, and science. Our approach will hopefully lead to new technology for high-quality imaging in dark environments, like outer space, and super-slow recording that will far exceed the capabilities of today's fastest cameras," says Prof. Hamamoto. He also states that even consumer-level cameras might timely benefit from progress in single-photon imaging.

We are certainly getting closer to a new era in digital photography, and studies like this one are crucial for paving the wave towards that future!

INFORMATION:

About The Tokyo University of Science

Tokyo University of Science (TUS) is a well-known and respected university, and the largest science-specialized private research university in Japan, with four campuses in central Tokyo and its suburbs and in Hokkaido. Established in 1881, the university has continually contributed to Japan's development in science through inculcating the love for science in researchers, technicians, and educators.

With a mission of "Creating science and technology for the harmonious development of nature, human beings, and society", TUS has undertaken a wide range of research from basic to applied science. TUS has embraced a multidisciplinary approach to research and undertaken intensive study in some of today's most vital fields. TUS is a meritocracy where the best in science is recognized and nurtured. It is the only private university in Japan that has produced a Nobel Prize winner and the only private university in Asia to produce Nobel Prize winners within the natural sciences field.

Website: https://www.tus.ac.jp/en/mediarelations/

About Professor Takayuki Hamamoto from Tokyo University of Science

Takayuki Hamamoto received Bachelor's and Master's degrees from Tokyo University of Science in 1992 and 1994, respectively. He proceeded to get a doctoral degree in electrical engineering from The University of Tokyo in 1997. He is currently a Professor at Tokyo University of Science and leads the Hamamoto Lab, which focuses on image processing and coding, imaging sensors, and very-large-scale integration. He has over 300 papers to his name and received multiple "best paper" and "best poster" awards from various workshops and symposiums. Prof. Hamamoto is also a member of the IEEE.

Funding information

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI under Grant JP19K12025 and Grant 20K19829.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-10

Peptides " short strings of amino acids" play a vital role in health and industry with a huge range of medical uses including in antibiotics, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer drugs. They are also used in the cosmetics industry and for enhancing athletic performance. Altering the structure of natural peptides to produce improved compounds is therefore of great interest to scientists and industry. But how the machineries that produce these peptides work still isn't clearly understood.

Associate Professor Max Cryle from Monash University's Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI) has revealed a key aspect of peptide machinery in a paper published in Nature Communications today that provides a key to the "Holy Grail" of re-engineering peptides..

The findings will advance his lab's work into ...

2021-05-10

A new study from the Harvard GenderSci Lab in the journal Human Fertility, "The Future of Sperm: A Biovariability Framework for Understanding Global Sperm Count Trends" questions the panic over apparent trends of declining human sperm count.

Recent studies have claimed that sperm counts among men globally, and especially from "Western" countries, are in decline, leading to apocalyptic claims about the possible extinction of the human species.

But the Harvard paper, by Marion Boulicault, Sarah S. Richardson, and colleagues, reanalyzes claims of precipitous human sperm declines, re-evaluating evidence presented in the widely-cited 2017 meta-analysis by Hagai Levine, Shanna ...

2021-05-10

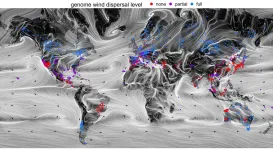

Berkeley -- Forests' ability to survive and adapt to the disruptions wrought by climate change may depend, in part, on the eddies and swirls of global wind currents, suggests a new study by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley.

Unlike animals, the trees that make up our planet's forests can't uproot and find new terrain if conditions get tough. Instead, many trees produce seeds and pollen that are designed to be carried away by the wind, an adaptation that helps them colonize new territories and maximize how far they can spread their genes.

The ...

2021-05-10

New research demonstrates that African and Asian leopards are more genetically differentiated from one another than polar bears and brown bears. Indeed, leopards are so different that they ought to be treated as two separate species, according to a team of researchers, among them, scientists from the University of Copenhagen. This new knowledge has important implications for better conserving this big and beautiful, yet widely endangered cat.

No one has any doubts about polar bears and brown bears being distinct species. Leopards, on the other hand, are considered one and the same, a single species, whether of African or Asian ...

2021-05-10

AURORA, Colo. (May 10, 2021) - Looking to safely block a gene linked to factors known to cause heart disease, scientists at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus may have found a new tool - light.

The study, published Monday in the journal Trends in Molecular Medicine, may solve a medical dilemma that has baffled scientists for years.

The gene, ANGPTL4, regulates fatty lipids in plasma. Scientists have found that people with lower levels of it also have reduced triglycerides and lipids, meaning less risk for cardiovascular disease.

But blocking the gene using antibodies triggered dangerous inflammation in mice. Complicating things further, the gene can also be beneficial in reducing the risk of myocardial ...

2021-05-10

Hamilton, ON (May 10, 2021) - It is well known that each person's gut bacteria is vital for digestion and overall health, but when does that gut microbiome start?

New research led by scientists from McMaster University and Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin in Germany has found it happens during and after birth, and not before.

McMaster researchers Deborah Sloboda and Katherine Kennedy examined prenatal stool (meconium) samples collected from 20 babies during breech Cesarean delivery.

"The key takeaway from our study is we are not colonized before birth. Rather, our relationship with our gut bacteria emerges ...

2021-05-10

URBANA, Ill. - Sweet corn growers and processors could be bringing in more profits by exploiting natural density tolerance traits in certain hybrids. That's according to 2019 research from USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and University of Illinois scientists.

But since root systems get smaller as plant density goes up, some in the industry are concerned about the risk of root lodging with greater sweet corn density. New research says those concerns are unjustified.

"Root lodging can certainly be a problem for sweet corn, but not because of plant density. What really matters is the specific hybrid and the environment, those major rainfall and wind events that set up conditions for root structural failure," says ...

2021-05-10

WHAT: A commentary from leaders at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, part of the NIH, discusses a new study showing that an extended-release injection of buprenorphine, a medication used to treat opioid use disorder, was preferred by patients compared to immediate-release buprenorphine, which must be taken orally every day. Extended-release formulations of medications used to treat opioid use disorder may be a valuable tool to address the current opioid addiction crisis and reduce its associated mortality. The study and the accompanying commentary were published May 10, 2021 in JAMA Network Open.

It is well established that medications used to treat ...

2021-05-10

Scientists at UC San Francisco are learning how immune cells naturally clear the body of defunct - or senescent - cells that contribute to aging and many chronic diseases. Understanding this process may open new ways of treating age-related chronic diseases with immunotherapy.

In a healthy state, these immune cells - known as invariant Natural Killer T (iNKT) cells - function as a surveillance system, eliminating cells the body senses as foreign, including senescent cells, which have irreparable DNA damage. But the iNKT cells become less active with age and other factors like obesity that contribute to chronic disease.

Finding ways to stimulate this natural surveillance system offers an alternative to senolytic ...

2021-05-10

A new study in Current Biology from the Institute of Genomics of the University of Tartu, Estonia has shed light on the genetic prehistory of populations in modern day Italy through the analysis of ancient human individuals during the Chalcolithic/Bronze Age transition around 4,000 years ago. The genomic analysis of ancient samples enabled researchers from Estonia, Italy, and the UK to date the arrival of the Steppe-related ancestry component to 3,600 years ago in Central Italy, also finding changes in burial practice and kinship structure during this transition.

In the last years, the genetic history of ancient individuals has been extensively studied focusing on ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] 'Unmaking' a move: Correcting motion blur in single-photon images

Researchers develop innovative deblurring method that works even for images with multiple objects moving independently