(Press-News.org) A new study of ancient DNA from horse fossils found in North America and Eurasia shows that horse populations on the two continents remained connected through the Bering Land Bridge, moving back and forth and interbreeding multiple times over hundreds of thousands of years.

The new findings demonstrate the genetic continuity between the horses that died out in North America at the end of the last ice age and the horses that were eventually domesticated in Eurasia and later reintroduced to North America by Europeans. The study has been accepted for publication in the journal Molecular Ecology and is currently available online.

"The results of this paper show that DNA flowed readily between Asia and North America during the ice ages, maintaining physical and evolutionary connectivity between horse populations across the Northern Hemisphere," said corresponding author Beth Shapiro, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

The study highlights the importance of the Bering Land Bridge as an ecological corridor for the movement of large animals between the continents during the Pleistocene, when massive ice sheets formed during glacial periods. Dramatically lower sea levels uncovered a vast land area known as Beringia, extending from the Lena River in Russia to the MacKenzie River in Canada, with extensive grasslands supporting populations of horses, mammoths, bison, and other Pleistocene fauna.

Paleontologists have long known that horses evolved and diversified in North America. One lineage of horses, known as the caballine horses (which includes domestic horses) dispersed into Eurasia over the Bering Land Bridge about 1 million years ago, and the Eurasian population then began to diverge genetically from the horses that remained in North America.

The new study shows that after the split, there were at least two periods when horses moved back and forth between the continents and interbred, so that the genomes of North American horses acquired segments of Eurasian DNA and vice versa.

"This is the first comprehensive look at the genetics of ancient horse populations across both continents," said first author Alisa Vershinina, a postdoctoral scholar working in Shapiro's Paleogenomics Laboratory at UC Santa Cruz. "With data from mitochondrial and nuclear genomes, we were able to see that horses were not only dispersing between the continents, but they were also interbreeding and exchanging genes."

Mitochondrial DNA, inherited only from the mother, is useful for studying evolutionary relationships because it accumulates mutations at a steady rate. It is also easier to recover from fossils because it is a small genome and there are many copies in every cell. The nuclear genome carried by the chromosomes, however, is a much richer source of evolutionary information.

The researchers sequenced 78 new mitochondrial genomes from ancient horses found across Eurasia and North America. Combining those with 112 previously published mitochondrial genomes, the researchers reconstructed a phylogenetic tree, a branching diagram showing how all the samples were related. With a location and an approximate date for each genome, they could track the movements of different lineages of ancient horses.

"We found Eurasian horse lineages here in North America and vice versa, suggesting cross-continental population movements. With dated mitochondrial genomes we can see when that shift in location happened," Vershinina explained.

The analysis showed two periods of dispersal between the continents, both coinciding with periods when the Bering Land Bridge would have been open. In the Middle Pleistocene, shortly after the two lineages diverged, the movement was mostly east to west. A second period in the Late Pleistocene saw movement in both directions, but mostly west to east. Due to limited sampling in some periods, the data may fail to capture other dispersal events, the researchers said.

The team also sequenced two new nuclear genomes from well-preserved horse fossils recovered in Yukon Territory, Canada. These were combined with 7 previously published nuclear genomes, enabling the researchers to quantify the amount of gene flow between the Eurasian and North American populations.

"The usual view in the past was that horses differentiated into separate species as soon as they were in Asia, but these results show there was continuity between the populations," said coauthor Ross MacPhee, a paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural History. "They were able to interbreed freely, and we see the results of that in the genomes of fossils from either side of the divide."

The new findings are sure to fuel the ongoing controversy over the management of wild horses in the United States, descendants of domestic horses brought over by Europeans. Many people regard those wild horses as an invasive species, while others consider them to be part of the native fauna of North America.

"Horses persisted in North America for a long time, and they occupied an ecological niche here," Vershinina said. "They died out about 11,000 years ago, but that's not much time in evolutionary terms. Present-day wild North American horses could be considered reintroduced, rather than invasive."

Coauthor Grant Zazula, a paleontologist with the Government of Yukon, said the new findings help reframe the question of why horses disappeared from North America. "It was a regional population loss rather than an extinction," he said. "We still don't know why, but it tells us that conditions in North America were dramatically different at the end of the last ice age. If horses hadn't crossed over to Asia, we would have lost them all globally."

INFORMATION:

This project was a large international collaborative effort involving researchers at multiple institutions working together to obtain DNA from fossils of ancient horses over a wide range of sites in Eurasia and North America. The coauthors include researchers from the University of Toulouse, France, the Arctic University of Norway, and other institutions in the United States, Canada, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Russia, and China. This work was supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation, Gordon & Betty Moore Foundation, and the American Wild Horse Campaign.

ITHACA, N.Y. - While examining the prevalence of listeria in agricultural soil throughout the U.S., Cornell University food scientists have stumbled upon five previously unknown and novel relatives of the bacteria.

The discovery, researchers said, will help food facilities identify potential growth niches that until now, may have been overlooked - thus improving food safety.

"This research increases the set of listeria species monitored in food production environments," said lead author Catharine R. Carlin, a doctoral student in food science. "Expanding the knowledge base to understand the diversity of listeria will save the commercial food world confusion and errors, as well as prevent ...

WASHINGTON, May 18, 2021 -- What are the most delicate and valuable things you have handled? How would you feel if your daily job involved handling human eggs and any mistakes would affect someone's life?

Typical egg collection requires a healthy woman to go through weeks of hormone therapy and then undergo an operation to retrieve eggs. These hard-earned and precious eggs are fertilized in vitro, and the best embryos are selected for future transfer.

But not all transfers succeed, which gives rise to the practice of freezing the extra embryos from an IVF cycle for future ...

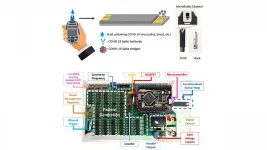

WASHINGTON, May 18, 2021 -- The COVID-19 pandemic made it clear technological innovations were urgently needed to detect, treat, and prevent the SARS-CoV-2 virus. A year and a half into this epidemic, waves of successive outbreaks and the dire need for new medical solutions -- especially testing -- continue to exist.

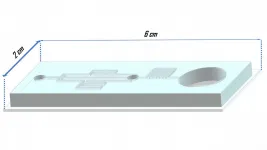

In the Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology B, researchers from the University of Florida and Taiwan's National Chiao Tung University report a rapid and sensitive testing method for COVID-19 biomarkers.

The researchers, who previously demonstrated ...

WASHINGTON, May 18, 2021 -- The COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced the pressing need to mitigate a fast-developing virus as well as antibiotic-resistant bacteria that are growing at alarming rates worldwide.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT), or using light to inactivate viruses, bacteria, and other microbes, has garnered promising results in recent decades for treating respiratory tract infections, such as pneumonia, and some types of cancer.

In Applied Physics Reviews, by AIP Publishing, researchers at Texas A&M University and the University of São Paulo in Brazil ...

Academic institutions need to do much more to support faculty members with disabilities and to create an environment in which they can thrive, argues a commentary published May 18 in the journal Trends in Neurosciences. The paper was written by Justin Yerbury, a cell and molecular neurobiologist who has amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and his wife, Rachel Yerbury, a research psychologist.

"We want people to understand how tough life is for people with a disability," says Justin Yerbury (@jjyerbury), a professor at the University of Wollongong in Australia. "When you add academia on top of ...

Twice as many eligible patients got screened for hepatitis C when it was already ordered for them compared to those who had to request it, according to a new study by researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Additionally, the patients in the study - whose average age was 63 - completed their screenings much more often when they were contacted via mail as opposed to electronic messaging. The study was published today in BMJ.

"We think that sending the lab order with outreach was so successful because it ...

University of California scientists have discovered genetic data that will help food crops like tomatoes and rice survive longer, more intense periods of drought on our warming planet.

Over the course of the last decade, the research team sought to create a molecular atlas of crop roots, where plants first detect the effects of drought and other environmental threats. In so doing, they uncovered genes that scientists can use to protect the plants from these stresses.

Their work, published today in the journal Cell, achieved a high degree of understanding of the root functions because it combined genetic data from different cells of tomato roots grown both indoors and outside.

"Frequently, ...

Bottom Line: The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that adults ages 45 to 75 be screened for colorectal cancer, lowering the age for screening that was previously 50 to 75. The USPSTF also recommends that clinicians selectively offer screening to adults 76 to 85 years of age. Colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of cancer death for both men and women in the United States. In 2016, 26% of eligible adults had never been screened and nearly one-third were not up to date with screening in 2018. The USPSTF routinely makes recommendations about the effectiveness of preventive care services and this statement replaces its 2016 recommendation.

To access the embargoed study: ...

Ikoma, Japan - In neurons, changes in the size of dendritic spines - small cellular protrusions involved in synaptic transmission - are thought to be a key mechanism underlying learning and memory. However, the specific way in which these structural changes occur remains unknown. In a study published in Cell Reports, researchers from Nara Institute of Science and Technology (NAIST) have revealed that the binding of cell adhesion molecules with actin, via an important linker protein in the structural backbone of synapses, is vital for this process of structural plasticity.

Actin proteins make up an important part of a cell's structure, or cytoskeleton, and allow for dynamic changes in this structure by forming ...

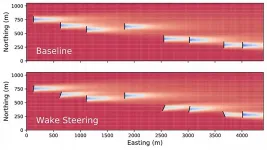

WASHINGTON, May 18, 2021 -- Wake steering is a strategy employed at wind power plants involving misaligning upstream turbines with the wind direction to deflect wakes away from downstream turbines, which consequently increases the net production of wind power at a plant.

In Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy, by AIP Publishing, researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) illustrate how wake steering can increase energy production for a large sampling of commercial land-based U.S. wind power plants.

While some plants showed less potential for wake steering due to unfavorable meteorological conditions or turbine layout, several wind power plants were ideal candidates ...