(Press-News.org) Killer flies can reach accelerations of over 3g when aerial diving to catch their prey - but at such high speeds they often miss because they can't correct their course.

These are the findings of a study by researchers at the Universities of Cambridge, Lincoln, and Minnesota, published today in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Killer flies (Coenosia attenuata) perform high-speed aerial dives to attack prey flying beneath them, reaching impressive accelerations of up to 36 m/s2, equivalent to 3.6 times the acceleration due to gravity (or 3.6g). This happens because they beat their wings as they fall, combining the acceleration of powered flight with the acceleration of gravity.

This is an impressive feat: diving Falcons, the fastest animals that predate in the air, achieve much lower accelerations of only 6.8m/s2. Falcons dive by folding their wings and simply letting gravity accelerate them towards their prey.

For the tiny Killer fly though, the high speeds achieved in aerial dives could come as a surprise - because the researchers think the fly doesn't take the effect of gravity into account when diving to intercept a target.

To get their results, the researchers built a transparent 'flight arena' and flew a dummy prey target through it at constant velocity. Killer flies were filmed with high speed video cameras as they attacked the target, and the researchers watched the footage back in slow motion - using this data to reconstruct the entire attack sequence in 3D.

The study found that Killer flies reached much higher accelerations in flight when taking off from the ceiling of the arena, compared to from the floor or walls. The flies beat their wings at a similar rate wherever they launched from, indicating that their flight speed is determined by a combination of wing power and gravity.

"When Killer flies took off from the floor or walls of the arena, they moved at the time when they could take the shortest path to the target. But they couldn't manage that when they took off from the ceiling because the high acceleration caused by gravity changed the expected flight path," said Sergio Rossoni, a PhD student in the University of Cambridge's Department of Zoology and first author of the paper.

By diving with super-high acceleration the Killer fly sometimes catches its target prey extremely quickly, but it often misses because its speed makes it challenging to change course mid-dive if the prey moves. But even if the fly doesn't land on target, the dive quickly reduces its distance from the prey so it can keep sight of it while making the final manoeuvers to catch it.

The researchers think the effect of not accounting for gravity during downward dives might be compensated by another advantage. High speed dives force the potential prey to change direction as the attacker approaches, but to do this the prey has to slow down - making it easier to catch.

Insects that hunt in the air usually attack their prey upwards, because the contrast of the prey against the sky makes it easier to see. Killer flies are unusual insect predators in this respect; hunting downwards against a visually cluttered ground, using eyes that have only coarse resolution, is more difficult.

"This research into miniature flies helps us understand what shortcuts are acceptable when survival depends on fast decisions and accurate actions, but the sensory capabilities and processing power of the predator are heavily constrained," said Professor Gonzalez-Bellido at the University of Minnesota, who led the study.

INFORMATION:

This research was funded by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and the Royal Society.

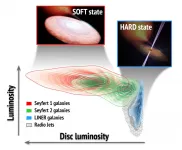

The researchers Juan A. Fernández-Ontiveros, of the Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica (INAF) in Rome and Teo Muñoz-Darias, of the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC), have written an article in which they describe the different states of activity of a large sample of supermassive black holes in the centres of galaxies. They have classified them using the behaviour of their closest "relations", the stellar mass black holes in X-ray binaries. The article has just been published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS).

Black holes range in mass from objects which have only a few ...

Mercury pollution is an issue of global concern due to its toxic effects. High levels have already been measured in Arctic organisms - with worrying effects on ecosystems and the food chain. So far, the Greenland Ice Sheet has not been taken into account as a part of the Arctic mercury cycle. Now, researchers led by Jon Hawkings of the German Research Centre for Geosciences in Potsdam and Florida State University show that meltwaters in the southwest of Greenland transport considerable amounts of mercury into the Arctic Ocean. Due to the large quantities detected, the researchers assume that they are of geological origin. They present their measurements in the current issue of Nature Geoscience.

Mercury: poison for humans and the environment - ...

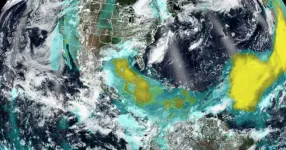

LAWRENCE -- For two weeks in June 2020, a massive dust plume from Saharan Africa crept westward across the Atlantic, blanketing the Caribbean and Gulf Coast states in the U.S. The dust storm was so strong, it earned the nickname "Godzilla."

Now, researchers from the University of Kansas have published a new study in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society parsing the mechanism that transported the dust. Their results explain a phenomenon that could occur more frequently in the years ahead due to climate change, affecting human health and transportation systems.

African dust darkened the skies of the Caribbean and American Gulf States thanks to a trio of atmospheric patterns, ...

Mitochondria are the cell's power plants and produce the majority of a cell's energy needs through an electrochemical process called electron transport chain coupled to another process known as oxidative phosphorylation. A number of different proteins in mitochondria facilitate these processes, but it's not fully understood how these proteins are arranged inside mitochondria and the factors that can influence their arrangement.

Now, scientists at the University of Copenhagen have used state-of-the-art proteomics technology to shine new light on how mitochondrial proteins gather into electron transport chain complexes, and further into so-called supercomplexes. The research, which is published in Cell Reports, also examined ...

Over the years, robots have gotten quite good at identifying objects -- as long as they're out in the open.

Discerning buried items in granular material like sand is a taller order. To do that, a robot would need fingers that were slender enough to penetrate the sand, mobile enough to wriggle free when sand grains jam, and sensitive enough to feel the detailed shape of the buried object.

MIT researchers have now designed a sharp-tipped robot finger equipped with tactile sensing to meet the challenge of identifying buried objects. In experiments, the aptly named ...

A mathematical model which can predict landslides that occur unexpectantly has been developed by two University of Melbourne scientists, with colleagues from GroundProbe-Orica and the University of Florence.

Professors Antoinette Tordesillas and Robin Batterham led the work over five years to develop and test the model SSSAFE (Spatiotemporal Slope Stability Analytics for Failure Estimation), which analyses slope stability over time to predict where and when a landslide or avalanche is likely to occur.

In a study published in Scientific Reports, the research team was ...

Discovered by Victor Hess in 1912, cosmic rays, relativisitic particles that shower Earth, contribute a signicant part of the energy density in the universe and carries unambiguous informations on various astrophysical processes . Yet until now, origin of cosmic rays is still a mystery.

A key problem in understanding the origin of cosmic rays is the searching for the acceleration site up to or even beyond Ultra-high energy (UHE). Such extreme accelerators are dubbed as PeVatrons. However, composed of subatomic particles, such as protons or atomic nuclei, cosmic rays are charged and lose ...

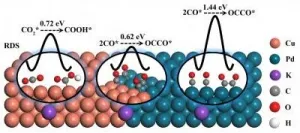

Using intermittent electric energy to convert excessive CO2 into C2 products, such as ethylene and ethanol, is an effective strategy to mitigate the greenhouse effect. Copper (Cu) is the only single metal catalyst which can converts CO2 into C2 products by electrochemical method, but with undesirable selectivity of C2 product. Therefore, how to improve the conversion efficiency of Cu-based catalysts for reducing CO2 to C2 product has attracted great attention.

Recently, a research team led by Prof. Min Liu from Central South University, China designed a Cu-Pd bimetallic electrocatalyst possessing CuPd(100) interface which can lower the energy barrier of C2 product generation. The electrocatalyst was obtained through using ...

WASHINGTON--People who eat too many refined carbs and fatty meats for dinner have a higher risk of heart disease than those who eat a similar diet for breakfast, according to a nationwide study published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

Cardiovascular diseases like congestive heart failure, heart attack and stroke are the number one cause of death globally, taking an estimated 17.9 million lives each year. Eating lots of saturated fat, processed meats and added sugars can raise your cholesterol and increase your risk of heart disease. Eating a heart-healthy diet with more whole carbohydrates like vegetables and grains and less meat can significantly offset the risk of cardiovascular disease.

"Meal timing along with food quality are important factors ...

The farming of livestock to feed the global appetite for animal products greatly contributes to global warming. A new study however shows that emission intensity per unit of animal protein produced from the sector has decreased globally over the past two decades due to greater production efficiency, raising questions around the extent to which methane emissions will change in the future and how we can better manage their negative impacts.

Despite what we know about the environmental cost of livestock production, the global appetite for animal products such as meat, eggs, and dairy continues to grow. The livestock sector is in fact the largest source of manmade methane emissions globally, and these emissions are projected ...