(Press-News.org) Half a billion tonnes of carbon emissions could be cut from Earth's atmosphere by improved management of peatlands, according to research partly undertaken at the University of Leicester.

A team of scientists, led by the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology (UKCEH), estimated the potential reduction of around 500 million tonnes in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by restoring all global agricultural peatlands.

Peatlands - a type of wetland, where dead vegetation is stopped from fully breaking down - cover just 3% of the global land surface, but store around 650 billion tonnes of carbon, around 100 billion tonnes more than all of the world's vegetation combined.

Dr Jörg Kaduk and Professor Sue Page, both from the University of Leicester's School of Geography, Geology and the Environment, are co-authors of the study published in Nature.

Professor Page said: "Our results present a challenge but also a great opportunity. Better water management in peatlands offers a potential 'win-win' - lower greenhouse gas emissions, improved soil health, extended agricultural lifetimes and reduced flood risk.

"For agricultural peatlands, the balance is between climate security, and livelihood and food security. Our study indicates that raising peatland water levels could allow peatland farmers to both reduce the climate impact of their activities and extend the usage of these very fertile organic soils through modified land management.

"However, this will not be possible in all locations, and will need to be considered alongside other options, including complete rewetting and ecosystem restoration."

In their natural state, peatlands can mitigate climate change by continuously removing the GHG carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and storing it securely under waterlogged conditions. But many peatland areas have been substantially modified by human activity, including drainage for agriculture and forest plantations.

This results in the release of around 1.5 billion tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere each year - which equates to three per cent of all global GHG emissions caused by human activities.

However, because large populations rely on these peatlands for their livelihoods, it may not be realistic to expect all agricultural peatlands to be fully returned to their natural condition in the near future.

The team therefore also analysed the impact of halving current drainage depths in croplands and grasslands on peat - which cover over 250,000km2 globally - and showed that this could still bring significant, realistic benefits for climate change mitigation. The study estimates this could cut emissions by around 500 million tonnes of CO2 a year, which equates to one per cent of all global GHG emissions caused by human activities.

Professor Chris Evans of UKCEH, who led the research, said: "Widespread peatland degradation will need to be addressed if the UK and other countries are to achieve their goal of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, as part of their contribution to the Paris climate agreement targets.

"Concerns over the economic and social consequences of rewetting agricultural peatlands have prevented large-scale restoration, but our study shows the development of locally appropriate mitigation measures could still deliver substantial reductions in emissions."

The scientists say potential reductions in GHG emissions from halving the drainage depth in agricultural peatlands are likely to be greater than estimated, given they did not include changes in emissions of the potent GHG nitrous oxide (N2O) which, like levels of CO2, are also likely to be higher in deep-drained agricultural peatlands.

The University of Leicester plays a prominent role in peatland research, as policy-makers look to make better use of this highly efficient resource. The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs this month published the England Peat Action Plan, which sets out the government's long-term vision for the management, protection and restoration of peatland. The plan utilises information derived from several research projects to which University of Leicester has made key contributions, particularly on the scale of GHG emissions from peatlands in eastern England.

Dr Kaduk and Professor Page are also working with the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy in order to better understand the role that agricultural management of peatlands plays in releasing N2O, as well as examining the long-term effects of agricultural use of peatlands.

Dr Kaduk added: "This study is just the first step towards fully exploring the emission reductions achievable through a whole range of differentiated local mitigation measures. For example, together with our farming partners we are determining the effects of farming practices on greenhouse gas emissions."

And earlier this month, Professor Page addressed the Climate Exp0 conference on Leicester's peatland work ahead of COP26, the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference due to be held in Glasgow this November, of which the University is part.

The study in Nature, 'Overriding water table control on managed peatland greenhouse gas emissions', involved authors from UKCEH, the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, the University of Leeds, The James Hutton Institute, Bangor University, Durham University, Queen Mary University of London, University of Birmingham, University of Leicester, Rothamsted Research and Frankfurt University.

INFORMATION:

Highlights

Among patients receiving dialysis in the Southeastern United States, those at for-profit dialysis facilities were less likely to be referred for kidney transplantation than those at non-profit facilities.

Rates of starting medical evaluations soon after referral and placing patients on a waitlist after evaluations were similar between the groups.

Washington, DC (May 26, 2021) -- New research indicates that patients with kidney failure who receive care at for-profit dialysis facilities are less likely to be referred for kidney transplants that those receiving care at non-profit ...

Scientists at the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC) have identified the first blood biomarker for myocarditis, a cardiac disease that is often misdiagnosed as myocardial infarction. Nevertheless, the diagnosis of myocarditis continues to be challenging in clinical practice.

The study, led by Dr. Pilar Martín and published today in The New England Journal of Medicine, has detected the presence of the human homolog of micro RNA miR-721 in the blood of myocarditis patients.

CNIC General Director Dr. Valentín Fuster emphasizes that these results of paramount importance because they establish the first validated blood marker with high sensitivity and specifity (>90%) for myocarditis. This will allow ...

Continuous skin-to-skin contact starting immediately after delivery even before the baby has been stabilised can reduce mortality by 25 per cent in infants with a very low birth weight. This according to a study in low- and middle-income countries coordinated by the WHO on the initiative of researchers at Karolinska Institutet published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Continuous skin-to-skin contact between infant and mother, or "Kangaroo Mother Care" (KMC), is one of the most effective ways to prevent infant mortality globally. The current recommendation from the World Health Organization (WHO) is that skin-to-skin contact should commence ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - Soil carbon storage, carbon capture and storage, biochar - mention these terms to most people, and a blank stare might be the response.

But frame these climate change mitigation strategies as being clean and green approaches to reversing the dangerous warming of our planet, and people might be more inclined to at least listen - and even to back these efforts.

A cross-disciplinary collaboration led by Jonathon Schuldt, associate professor of communication at Cornell University, found that a majority of the U.S. public is supportive of soil carbon storage as a climate change mitigation strategy, particularly when that and similar approaches are seen as "natural" strategies.

"To me, that psychology part - that's really interesting," Schuldt ...

With brilliant colors and picturesque shapes, many crystals are wonders of nature. Some crystals are also wonders of science, with transformative applications in electronics and optics. Understanding how best to grow such crystals is key to further advances.

Scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory, along with three universities, have revealed new insights into the mechanism behind how gallium nitride crystals grow at the atomic scale.

Gallium nitride crystals are already in wide use in light-emitting diodes, better known as LEDs. They might also be applied to form transistors for high-power switching electronics to make electric grids more energy efficient and smarter. The use of such "smart grids," which ...

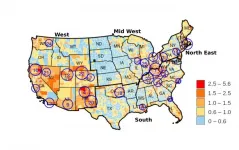

The opioid epidemic is taking a deadly toll on people in disproportionate clusters from Cape Cod to San Diego, according to a new study by the University of Cincinnati.

Fatal opiate overdoses are most prevalent among six states: Ohio, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, West Virginia, Indiana and Tennessee. But researchers identified 25 hot spots of fatal opioid overdoses nationwide using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The study demonstrates how both widespread and localized the problem of substance use disorders can be, UC assistant professor and co-author Diego Cuadros ...

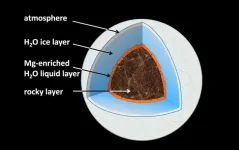

What is happening deep beneath the surface of ice planets? Is there liquid water, and if so, how does it interact with the planetary rocky "seafloor"? New experiments show that on water-ice planets between the size of our Earth and up to six times this size, water selectively leaches magnesium from typical rock minerals. The conditions with pressures of hundred thousand atmospheres and temperatures above one thousand degrees Celsius were recreated in a lab and mimicked planets similar, but smaller than Neptune and Uranus.

The mechanisms of water-rock interaction at the Earth's surface are well known, and the picture of ...

Modern-day agriculture faces two major dilemmas: how to produce enough food to feed the growing human population and how to minimize environmental damage associated with intensive agriculture. Keeping more nitrogen in soil as ammonium may be one key way to address both challenges, according to a new paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Today's use of nitrogen fertilizers contributes heavily to greenhouse gas emissions, air pollution, and water pollution, but they are also essential for growing crops. Reducing this pollution is critical, but nitrogen use is likely to grow with increased food production. At ...

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- One of the most important and widespread reef-building corals, known as cauliflower coral, exhibits strong partnerships with certain species of symbiotic algae, and these relationships have persisted through periods of intense climate fluctuations over the last 1.5 million years, according to a new study led by researchers at Penn State. The findings suggest that these corals and their symbiotic algae may have the capacity to adjust to modern-day increases in ocean warming, at least over the coming decades.

Cauliflower corals -- which are in the genus Pocillopora -- are branching corals that provide critical habitat for one-quarter of the world's fish and many kinds of invertebrates, such as lobsters, sea urchins and giant clams. ...

To help patients manage their mental wellness between appointments, researchers at Texas A&M University have developed a smart device-based electronic platform that can continuously monitor the state of hyperarousal, one of the signs of psychiatric distress. They said this advanced technology could read facial cues, analyze voice patterns and integrate readings from built-in vital signs sensors on smartwatches to determine if a patient is under stress.

Furthermore, the researchers noted that the technology could provide feedback and alert care teams if there is an abrupt deterioration in the patient's mental health.

"Mental health can change very rapidly, and a lot of these changes remain hidden from providers or counselors," said Dr. Farzan Sasangohar, assistant ...