(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA, CA--Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, most people in the United States already had been sick with a coronavirus, albeit a far less dangerous one. That's because at least four coronaviruses in the same general family as SARS-CoV-2 cause the benign yet annoying illness known as the common cold.

In a new study that appears in Nature Communications, scientists from Scripps Research investigated how the immune system's previous exposure to cold-causing coronaviruses impact immune response to COVID-19. In doing so, they discovered one cross-reactive coronavirus antibody that's triggered during a COVID-19 infection.

The findings will help in the pursuit of a vaccine or antibody treatment that works against most or all coronaviruses, says senior author Raiees Andrabi, PhD, an investigator in the Department of Immunology and Microbiology.

"By examining blood samples collected before the pandemic and comparing those with samples from people who had been sick with COVID-19, we were able to pinpoint antibody types that cross reacted with benign coronaviruses as well as SARS-CoV-2," says Andrabi, who works closely with the laboratory of professor Dennis Burton, PhD.

In later tests, the antibody also neutralized SARS-CoV-1, the coronavirus that causes SARS, or severe acute respiratory syndrome.

"We were able to determine that this type of cross-reactive antibody is likely produced by a memory B cell that's initially exposed to a coronavirus that causes the common cold, and is then recalled during a COVID-19 infection," Andrabi says.

Memory B cells are an essential part of the immune system. They "remember" initial disease threats and can circulate in the bloodstream for decades, ready to be called back into action if the threat emerges again. These cells are responsible for producing targeted antibodies.

The discovery may be an important step in the eventual development of a pan-coronavirus vaccine, which would be able to protect against potential coronaviruses that emerge in the future, says Burton, the James and Jessie Minor Chair in Immunology in the Department of Immunology & Microbiology at Scripps Research.

"Another deadly coronavirus will likely emerge again in the future--and when it does, we want to be better prepared," Burton says. "Our identification of a cross-reactive antibody against SARS-CoV-2 and the more common coronaviruses is a promising development on the way to a broad-acting vaccine or therapy."

Burton's lab is also investigating broadly neutralizing antibodies that can be harnessed to protect against many forms of influenza, which is another virus likely to cause a pandemic in the future.

In the new study, the team used electron microscopy to understand how the cross-reactive antibody is able to neutralize a range of coronaviruses. They saw that it mostly binds to the base of the virus's spike protein, an area that doesn't change much from strain to strain, says first author Ge "Sophie" Song, a graduate student in the Burton laboratory.

"The study highlights how important it is to fully understand the nature of preexisting immunity, especially in regard to coronaviruses," Song says. "Earlier exposure to a coronavirus, even a benign virus that causes colds, impacts the nature and level of antibodies produced when more serious coronavirus threats emerge."

INFORMATION:

The study, "Cross-reactive serum and memory B-cell responses to spike protein in SARS-CoV-2 and endemic coronavirus infection," is authored by Ge Song, Wan-ting He, Sean Callaghan, Fabio Anzanello, Deli Huang, James Ricketts, Jonathan Torres, Nathan Beutler, Linghang Peng, Sirena Vargas, Jon Cassell, Mara Parren, Linlin Yang, Caroline Ignacio, Davey Smith, James Voss, David Nemazee, Andrew Ward, Thomas Rogers, Dennis Burton and Raiees Andrabi.

Funding for this research was provided by NIH CHAVD and R01 awards, the IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Center, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the John and Mary Tu Foundation and the James B. Pendleton Charitable Trust.

Although it is not spread through human contact, Francisella tularensis is one of the most infectious pathogenic bacteria known to science--so virulent, in fact, that it is considered a serious potential bioterrorist threat. It is thought that humans can contract respiratory tularemia, or rabbit fever--a rare and deadly disease--by inhaling as few as 10 airborne organisms.

Northern Arizona University professor David Wagner, director of the Pathogen and Microbiome Institute's (PMI) Biodefense and Disease Ecology Center, began a three-year project in 2018 to better understand the life cycle and behavior of F. tularensis, ...

An estimated one in seven Ohio women of adult, reproductive age has visited a crisis pregnancy center, a new study has found.

In a survey of 2,529 women, almost 14% said they'd ever attended a center. The prevalence was more than twice as high among Black women and 1.6 times as high among those in the lowest socioeconomic group, found a research team from The Ohio State University. Their study appears in the journal Contraception.

Crisis pregnancy centers are often supported by religious organizations and are designed to discourage women with unintended pregnancies from choosing abortion, though they don't typically advertise themselves as anti-abortion. In Ohio, where more than 100 centers are spread throughout the state, they are funded by state dollars. In 2019, during ...

Local management of coral reefs to ease environmental stressors, such as overfishing or pollution, could increase reefs' chances of recovery after devastating coral bleaching events caused by climate change, a new study finds. The results suggest that caring for reefs on a local scale might help them persist globally. When waters warm, corals can die quickly and en masse in coral bleaching events. Marine warming due to climate change has resulted in sharp increases in both the frequency and magnitude of these mass mortality events, which have already caused severe ...

An exoskeleton can reduce the metabolic cost of walking not by adding energy or by recycling energy from one gait phase to another, as other exoskeletons have done, but by removing the kinetic energy of a striding person's swinging leg so they don't have to tense their muscles so much. Tested in ten healthy males, it also converted the extracted kinetic energy to useable electricity. Although humans are exceptional walkers, walking is metabolically expensive and requires more energy than any other activity of daily living. Exoskeletons and exosuits - wearable devices designed to work along with the body's musculoskeletal system - have been shown to reduce this cost by adding or recycling energy to assist the body's movement. These and other ...

There is heightened public awareness that the world's oceans are under duress, with over-fishing and plastic pollution as some of the more tangible problems. Now, seabirds are calling attention to another problem and have delivered a warning message.

Serving as translators of the birds' message, an international team of 40 scientists led by William Sydeman at the Farallon Institute in northern California published findings on May 28 in the journal Science that some seabirds are struggling to raise young where the globe is most rapidly warming - in the northern hemisphere.

Using over 50 years of data from 67 seabird species across the globe, the team found ...

In a study that uniquely evaluates marine ecosystem responses to a changing climate by hemisphere, researchers report that the fish-eating, surface-foraging bird species of the Northern Hemisphere suffered greater breeding productivity stresses over the last half-century than their Southern Hemisphere counterparts. The findings suggest the need for ocean management at hemispheric scales and underscore the importance of long-term seabird monitoring programs - some of which are already under threat - by illustrating the critical role that seabirds play as sentinels of global marine change. To date, global understanding of ocean change has not explicitly considered differences, ...

Australian researchers recently reported a sharp decline in the abundance of coral along the Great Barrier Reef. Scientists are seeing similar declines in coral colonies throughout the world, including reefs off of Hawaii, the Florida Keys and in the Indo-Pacific region.

The widespread decline is fueled in part by climate-driven heat waves that are warming the world's oceans and leading to what's known as coral bleaching, the breakdown of the mutually beneficial relationship between corals and resident algae.

But other factors are contributing to the decline ...

HOUSTON - (May 27, 2021) - One hundred fifty years ago, Dmitri Mendeleev created the periodic table, a system for classifying atoms based on the properties of their nuclei. This week, a team of biologists studying the tree of life has unveiled a new classification system for cell nuclei and discovered a method for transmuting one type of cell nucleus into another.

The study, which appears this week in the journal Science, emerged from several once-separate efforts. One of these centered on the DNA Zoo, an international consortium spanning dozens of institutions including Baylor College of ...

Many seabirds in the Northern Hemisphere are struggling to breed -- and in the Southern Hemisphere, they may not be far behind. These are the conclusions of a study, published May 28 in Science, analyzing more than 50 years of breeding records for 67 seabird species worldwide.

The international team of scientists -- led by William Sydeman at the Farallon Institute in California -- discovered that reproductive success decreased in the past half century for fish-eating seabirds north of the equator. The Northern Hemisphere has suffered greater impacts from human-caused climate change and other human activities, like overfishing.

Seabirds include albatrosses, puffins, murres, penguins and other birds. Whether they ...

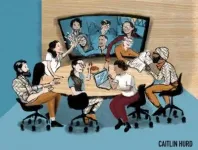

A new paper, published recently in PLOS Computational Biology by a team including UMass Amherst researchers, seeks to help scientists structure their lab-group meetings so that they are more inclusive, more productive and, ultimately, lead to better science.

The word "scientist" might conjure images of lab-coated researchers tending bubbling beakers or building supercomputers, but an enormous amount of scientific work takes place around a conference table during weekly group meetings. "There is plenty of good research showing that diversity and inclusion make the science itself better," says Kadambari Devarajan, one of the paper's co-lead authors and a graduate ...