(Press-News.org) Nobody likes driving in a blizzard, including autonomous vehicles. To make self-driving cars safer on snowy roads, engineers look at the problem from the car's point of view.

A major challenge for fully autonomous vehicles is navigating bad weather. Snow especially confounds crucial sensor data that helps a vehicle gauge depth, find obstacles and keep on the correct side of the yellow line, assuming it is visible. Averaging more than 200 inches of snow every winter, Michigan's Keweenaw Peninsula is the perfect place to push autonomous vehicle tech to its limits. In two papers presented at SPIE Defense + Commercial Sensing 2021, researchers from Michigan Technological University discuss solutions for snowy driving scenarios that could help bring self-driving options to snowy cities like Chicago, Detroit, Minneapolis and Toronto.

Just like the weather at times, autonomy is not a sunny or snowy yes-no designation. Autonomous vehicles cover a spectrum of levels, from cars already on the market with blind spot warnings or braking assistance, to vehicles that can switch in and out of self-driving modes, to others that can navigate entirely on their own. Major automakers and research universities are still tweaking self-driving technology and algorithms. Occasionally accidents occur, either due to a misjudgment by the car's artificial intelligence (AI) or a human driver's misuse of self-driving features.

Humans have sensors, too: our scanning eyes, our sense of balance and movement, and the processing power of our brain help us understand our environment. These seemingly basic inputs allow us to drive in virtually every scenario, even if it is new to us, because human brains are good at generalizing novel experiences. In autonomous vehicles, two cameras mounted on gimbals scan and perceive depth using stereo vision to mimic human vision, while balance and motion can be gauged using an inertial measurement unit. But, computers can only react to scenarios they have encountered before or been programmed to recognize.

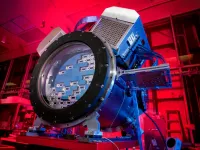

Since artificial brains aren't around yet, task-specific artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms must take the wheel -- which means autonomous vehicles must rely on multiple sensors. Fisheye cameras widen the view while other cameras act much like the human eye. Infrared picks up heat signatures. Radar can see through the fog and rain. Light detection and ranging (lidar) pierces through the dark and weaves a neon tapestry of laser beam threads.

"Every sensor has limitations, and every sensor covers another one's back," said Nathir Rawashdeh, assistant professor of computing in Michigan Tech's College of Computing and one of the study's lead researchers. He works on bringing the sensors' data together through an AI process called sensor fusion.

"Sensor fusion uses multiple sensors of different modalities to understand a scene," he said. "You cannot exhaustively program for every detail when the inputs have difficult patterns. That's why we need AI."

Rawashdeh's Michigan Tech collaborators include Nader Abu-Alrub, his doctoral student in electrical and computer engineering, and Jeremy Bos, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering, along with master's degree students and graduates from Bos' lab: Akhil Kurup, Derek Chopp and Zach Jeffries. Bos explains that lidar, infrared and other sensors on their own are like the hammer in an old adage. "'To a hammer, everything looks like a nail,'" quoted Bos. "Well, if you have a screwdriver and a rivet gun, then you have more options."

Most autonomous sensors and self-driving algorithms are being developed in sunny, clear landscapes. Knowing that the rest of the world is not like Arizona or southern California, Bos's lab began collecting local data in a Michigan Tech autonomous vehicle (safely driven by a human) during heavy snowfall. Rawashdeh's team, notably Abu-Alrub, poured over more than 1,000 frames of lidar, radar and image data from snowy roads in Germany and Norway to start teaching their AI program what snow looks like and how to see past it.

"All snow is not created equal," Bos said, pointing out that the variety of snow makes sensor detection a challenge. Rawashdeh added that pre-processing the data and ensuring accurate labeling is an important step to ensure accuracy and safety: "AI is like a chef -- if you have good ingredients, there will be an excellent meal," he said. "Give the AI learning network dirty sensor data and you'll get a bad result."

Low-quality data is one problem and so is actual dirt. Much like road grime, snow buildup on the sensors is a solvable but bothersome issue. Once the view is clear, autonomous vehicle sensors are still not always in agreement about detecting obstacles. Bos mentioned a great example of discovering a deer while cleaning up locally gathered data. Lidar said that blob was nothing (30% chance of an obstacle), the camera saw it like a sleepy human at the wheel (50% chance), and the infrared sensor shouted WHOA (90% sure that is a deer).

Getting the sensors and their risk assessments to talk and learn from each other is like the Indian parable of three blind men who find an elephant: each touches a different part of the elephant -- the creature's ear, trunk and leg -- and comes to a different conclusion about what kind of animal it is. Using sensor fusion, Rawashdeh and Bos want autonomous sensors to collectively figure out the answer -- be it elephant, deer or snowbank. As Bos puts it, "Rather than strictly voting, by using sensor fusion we will come up with a new estimate."

While navigating a Keweenaw blizzard is a ways out for autonomous vehicles, their sensors can get better at learning about bad weather and, with advances like sensor fusion, will be able to drive safely on snowy roads one day.

INFORMATION:

Ionizing radiation is used for treating nearly half of all cancer patients. Radiotherapy works by damaging the DNA of cancer cells, and cells sustaining so much DNA damage that they cannot sufficiently repair it will soon cease to replicate and die. It's an effective strategy overall, and radiotherapy is a common frontline cancer treatment option. Unfortunately, many cancers have subsets of cells that are able to survive initial radiotherapeutic regimens by developing mechanisms that are able to repair the DNA damage. This often results in resistance to further radiation as cancerous growth recurs. But until recently, little was known about exactly what happens in the genomes of cancer cells following radiotherapy.

To probe the traits of post-radiotherapy cancer ...

May 27, 2021 - Patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty (THA) show significant reduction in pain and other symptoms and improvement in walking gait biomechanics. However, those improvements do not lead to increased daily physical activity levels, reports a study in The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio in partnership with Wolters Kluwer.

The findings "present a worrying picture that while patients have the opportunity to be more physically active through improvements in functional capacity, their physical behaviors do not change," according to the new research, led by Jasvir S. Bahl of the University of South Australia, Adelaide, in collaboration with the University of Adelaide, Flinders University, ...

In 29 new scientific papers, the Dark Energy Survey examines the largest-ever maps of galaxy distribution and shapes, extending more than 7 billion light-years across the Universe. The extraordinarily precise analysis, which includes data from the survey's first three years, contributes to the most powerful test of the current best model of the Universe, the standard cosmological model. However, hints remain from earlier DES data and other experiments that matter in the Universe today is a few percent less clumpy than predicted.

New results from the Dark Energy Survey (DES) use the largest-ever sample ...

LA JOLLA, CA--Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, most people in the United States already had been sick with a coronavirus, albeit a far less dangerous one. That's because at least four coronaviruses in the same general family as SARS-CoV-2 cause the benign yet annoying illness known as the common cold.

In a new study that appears in Nature Communications, scientists from Scripps Research investigated how the immune system's previous exposure to cold-causing coronaviruses impact immune response to COVID-19. In doing so, they discovered one cross-reactive coronavirus antibody that's triggered during a COVID-19 infection.

The findings will help in the pursuit of a vaccine or antibody ...

Although it is not spread through human contact, Francisella tularensis is one of the most infectious pathogenic bacteria known to science--so virulent, in fact, that it is considered a serious potential bioterrorist threat. It is thought that humans can contract respiratory tularemia, or rabbit fever--a rare and deadly disease--by inhaling as few as 10 airborne organisms.

Northern Arizona University professor David Wagner, director of the Pathogen and Microbiome Institute's (PMI) Biodefense and Disease Ecology Center, began a three-year project in 2018 to better understand the life cycle and behavior of F. tularensis, ...

An estimated one in seven Ohio women of adult, reproductive age has visited a crisis pregnancy center, a new study has found.

In a survey of 2,529 women, almost 14% said they'd ever attended a center. The prevalence was more than twice as high among Black women and 1.6 times as high among those in the lowest socioeconomic group, found a research team from The Ohio State University. Their study appears in the journal Contraception.

Crisis pregnancy centers are often supported by religious organizations and are designed to discourage women with unintended pregnancies from choosing abortion, though they don't typically advertise themselves as anti-abortion. In Ohio, where more than 100 centers are spread throughout the state, they are funded by state dollars. In 2019, during ...

Local management of coral reefs to ease environmental stressors, such as overfishing or pollution, could increase reefs' chances of recovery after devastating coral bleaching events caused by climate change, a new study finds. The results suggest that caring for reefs on a local scale might help them persist globally. When waters warm, corals can die quickly and en masse in coral bleaching events. Marine warming due to climate change has resulted in sharp increases in both the frequency and magnitude of these mass mortality events, which have already caused severe ...

An exoskeleton can reduce the metabolic cost of walking not by adding energy or by recycling energy from one gait phase to another, as other exoskeletons have done, but by removing the kinetic energy of a striding person's swinging leg so they don't have to tense their muscles so much. Tested in ten healthy males, it also converted the extracted kinetic energy to useable electricity. Although humans are exceptional walkers, walking is metabolically expensive and requires more energy than any other activity of daily living. Exoskeletons and exosuits - wearable devices designed to work along with the body's musculoskeletal system - have been shown to reduce this cost by adding or recycling energy to assist the body's movement. These and other ...

There is heightened public awareness that the world's oceans are under duress, with over-fishing and plastic pollution as some of the more tangible problems. Now, seabirds are calling attention to another problem and have delivered a warning message.

Serving as translators of the birds' message, an international team of 40 scientists led by William Sydeman at the Farallon Institute in northern California published findings on May 28 in the journal Science that some seabirds are struggling to raise young where the globe is most rapidly warming - in the northern hemisphere.

Using over 50 years of data from 67 seabird species across the globe, the team found ...

In a study that uniquely evaluates marine ecosystem responses to a changing climate by hemisphere, researchers report that the fish-eating, surface-foraging bird species of the Northern Hemisphere suffered greater breeding productivity stresses over the last half-century than their Southern Hemisphere counterparts. The findings suggest the need for ocean management at hemispheric scales and underscore the importance of long-term seabird monitoring programs - some of which are already under threat - by illustrating the critical role that seabirds play as sentinels of global marine change. To date, global understanding of ocean change has not explicitly considered differences, ...