(Press-News.org) Phosphate pollution in rivers, lakes and other waterways has reached dangerous levels, causing algae blooms that starve fish and aquatic plants of oxygen. Meanwhile, farmers worldwide are coming to terms with a dwindling reserve of phosphate fertilizers that feed half the world's food supply.

Inspired by Chicago's many nearby bodies of water, a Northwestern University-led team has developed a way to repeatedly remove and reuse phosphate from polluted waters. The researchers liken the development to a "Swiss Army knife" for pollution remediation as they tailor their membrane to absorb and later release other pollutants.

The research will be published during the week of May 31 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

Phosphorus underpins both the world's food system and all life on earth. Every living organism on the planet requires it: phosphorous is in cell membranes, the scaffolding of DNA and in our skeleton. Though other key elements like oxygen and nitrogen can be found in the atmosphere, phosphorous has no analog. The small fraction of usable phosphorous comes from the Earth's crust, which takes thousands or even millions of years to weather away. And our mines are running out.

A 2021 article in The Atlantic by Julia Rosen cited Isaac Asimov's 1939 essay, in which the American writer and chemist dubbed phosphorous "life's bottleneck."

Given the shortage of this non-renewable natural resource, it is sadly ironic that many of our lakes are suffering from a process known as eutrophication, which occurs when too many nutrients enter a natural water source. As phosphate and other minerals build up, aquatic vegetation and algae become too dense, depleting oxygen from water and ultimately killing aquatic life.

"We used to reuse phosphate a lot more," said Stephanie Ribet, the paper's first author. "Now we just pull it out of the ground, use it once and flush it away into water sources after use. So, it's a pollution problem, a sustainability problem and a circular economy problem."

Ecologists and engineers traditionally have developed tactics to address the mounting environmental and public health concerns around phosphate by eliminating phosphate from water sources. Only recently has the emphasis shifted away from removing to recovering phosphate.

"One can always do certain things in a laboratory setting," said Vinayak Dravid, the study's corresponding author. "But there's a Venn Diagram when it comes to scaling up, where you need to be able to scale the technology, you want it to be effective and you want it to be affordable. There was nothing in that intersection of the three before, but our sponge seems to be a platform that meets all these criteria."

Dravid is the Abraham Harris Professor of Materials Science and Engineering at Northwestern's McCormick School of Engineering, the founding director of the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental Center (NUANCE), and director of the Soft and Hybrid Nanotechnology Experimental Resource (SHyNE). Dravid also serves as the director of global initiatives for Northwestern's International Institute of Nanotechnology. Ribet is a Ph.D. student in Dravid's lab and the paper's first author.

The team's Phosphate Elimination and Recovery Lightweight (PEARL) membrane is a porous, flexible substrate (such as a coated sponge, cloth or fibers) that selectively sequesters up to 99% of phosphate ions from polluted water. Coated with nanostructures that bind to phosphate, the PEARL membrane can be tuned by controlling the pH to either absorb or release nutrients to allow for phosphate recovery and reuse of the membrane for many cycles.

Current methods to remove phosphate are based on complex, lengthy, multi-step methods. Most of them do not also recover the phosphate during removal and ultimately generate a great deal of physical waste. The PEARL membrane provides a simple one-step process to remove phosphate that also efficiently recovers it. It's also reusable and generates no physical waste.

Using samples from Chicago's Water Reclamation District, the researchers tested their theory with the added complexity of real water samples.

"We often call this a 'nanoscale solution to a gigaton problem,'" Dravid said. "In many ways the nanoscale interactions that we study have implications for macrolevel remediation."

The team has demonstrated that the sponge-based approach is effective on scales, ranging from milligrams to kilograms, suggesting promise in scaling even further.

This research builds on a former development from the same team - Vikas Nandwana, a member of the Dravid group and co-author on the present study was the first author -called the OHM (oleophilic hydrophobic multifunctional) sponge that used the same sponge platform to selectively remove and recover oil resulting from oil contamination in water. By modifying the nanomaterial coating in the membrane, the team plans to next use their "plug-and-play"-like framework to go after heavy metals. Ribet also said multiple pollutants could be addressed at once by applying multiple materials with tailored affinities.

"This water remediation challenge hits so close to home," Ribet said. "The western basin of Lake Erie is one of the main areas you think of when it comes to eutrophication, and I was inspired by learning more about the water remediation challenges in our Great Lakes neighborhood."

INFORMATION:

The research, "Phosphate Elimination and Recovery Lightweight (PEARL) Membrane: A Sustainable Environmental Remediation Approach," was supported by the National Science Foundation (award number DMR-1929356). Research for the paper made use of SHyNE resource facilities, which are supported by the NSF National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (NSF-NCCI) program.

Benjamin Shindel, Roberto dos Reis and Vikas Nandwana -- all from Northwestern -- coauthored the paper.

Very high atmospheric CO2 levels can explain the high temperatures on the still young Earth three to four billion years ago. At the time, our Sun shone with only 70 to 80 per cent of its present intensity. Nevertheless, the climate on the young Earth was apparently quite warm because there was hardly any glacial ice. This phenomenon is known as the 'paradox of the young weak Sun.' Without an effective greenhouse gas, the young Earth would have frozen into a lump of ice. Whether CO2, methane, or an entirely different greenhouse gas heated up planet Earth is a matter of debate among scientists. New research by Dr ...

Art Garfunkel once described his legendary musical chemistry with Paul Simon, "We meet somewhere in the air through the vocal cords ... ." But a new study of duetting songbirds from Ecuador, the plain-tail wren (Pheugopedius euophrys), has offered another tune explaining the mysterious connection between successful performing duos.

It's a link of their minds, and it happens, in fact, as each singer mutes the brain of the other as they coordinate their duets.

In a study published May 31 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team of researchers studying brain ...

Three groups (Dr. James Birchler's group from University of Missouri, Dr. Jan Barto's group from Institute of Experimental Botany of the Czech Academy of Sciences and Dr. HAN Fangpu's group from the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences) recently reported a reference sequence for the supernumerary B chromosome in maize in a study published online in PNAS (doi:10.1073/pnas.2104254118).

Supernumerary B chromosomes persist in thousands of plant and animal genomes despite being nonessential. They are maintained in populations by mechanisms of "drive" that make them inherited at higher than typical Mendelian rates. Key properties such as its origin, evolution, and the molecular mechanism for its accumulation in ...

While it is widely accepted that climate change drove the evolution of our species in Africa, the exact character of that climate change and its impacts are not well understood. Glacial-interglacial cycles strongly impact patterns of climate change in many parts of the world, and were also assumed to regulate environmental changes in Africa during the critical period of human evolution over the last ~1 million years. The ecosystem changes driven by these glacial cycles are thought to have stimulated the evolution and dispersal of early humans.

A paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) this week challenges this view. Dr. Kaboth-Bahr ...

The Sahara has not always been covered by only sand and rocks. During the period from 14,500 to 5,000 years ago large areas of North Africa were more heavily populated, and where there is desert today the land was green with vegetation. This is evidenced by various sites with rock paintings showing not only giraffes and crocodiles, but even illustrating people swimming in the "Cave of Swimmers". This period is known as the Green Sahara or African Humid Period. Until now, researchers have assumed that the necessary rain was brought from the tropics through an enhanced summer monsoon. The northward shift of the monsoon was attributed to rotation of the Earth's tilted axis that produces higher levels of ...

An emotion regulation strategy known as cognitive reappraisal helped reduce the typically heightened and habitual attention to drug-related cues and contexts in cocaine-addicted individuals, a study by Mount Sinai researchers has found. In a paper published in PNAS, the team suggested that this form of habit disruption, mediated by the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of the brain, could play an important role in reducing the compulsive drug-seeking behavior and relapse that are the hallmarks, and long-standing challenges, of addiction.

"Relapse in addiction is often precipitated by heightened attention-bias to drug-related cues, which could consist of sights, smells, ...

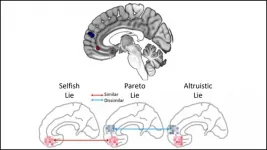

You may think a little white lie about a bad haircut is strictly for your friend's benefit, but your brain activity says otherwise. Distinct activity patterns in the prefrontal cortex reveal when a white lie has selfish motives, according to new research published in JNeurosci.

White lies -- formally called Pareto lies -- can benefit both parties, but their true motives are encoded by the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC). This brain region computes the value of different social behaviors, with some subregions focusing on internal motivations and others on external ones. Kim and Kim predicted activity patterns in these subregions could elucidate the true motive behind white lies.

The research team deployed a stand in for white lies, having participants tell lies to earn a reward ...

By including multi-ethnic participants, a largescale genetic study has identified more regions of the genome linked to type 2 diabetes-related traits than if the research had been conducted in Europeans alone.

The international MAGIC collaboration, made up of more than 400 global academics, conducted a genome-wide association meta-analysis led by the University of Exeter. Now published in Nature Genetics, their findings demonstrate that expanding research into different ancestries yields more and better results, as well as ultimately benefitting global patient care.

Up to now, nearly 87 per cent of ...

Artificial intelligence promises to be a powerful tool for improving the speed and accuracy of medical decision-making to improve patient outcomes. From diagnosing disease, to personalizing treatment, to predicting complications from surgery, AI could become as integral to patient care in the future as imaging and laboratory tests are today.

But as University of Washington researchers discovered, AI models -- like humans -- have a tendency to look for shortcuts. In the case of AI-assisted disease detection, these shortcuts could lead to diagnostic errors if deployed in clinical settings.

In a new paper published May 31 in Nature Machine Intelligence, ...

The Water Oxidation Reaction (WOR) is one of the most important reactions on the planet since it is the source of nearly all the atmosphere's oxygen. Understanding its intricacies can hold the key to improve the efficiency of the reaction. Unfortunately, the reaction's mechanisms are complex and the intermediates highly unstable, thus making their isolation and characterisation extremely challenging. To overcome this, scientists are using molecular catalysts as models to understand the fundamental aspects of water oxidation - particularly the oxygen-oxygen bond-forming reaction.

For the first time, scientists in ICIQ's ...