(Press-News.org) The term "doomscrolling" describes the act of endlessly scrolling through bad news on social media and reading every worrisome tidbit that pops up, a habit that unfortunately seems to have become common during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The biology of our brains may play a role in that. Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified specific areas and cells in the brain that become active when an individual is faced with the choice to learn or hide from information about an unwanted aversive event the individual likely has no power to prevent.

The findings, published June 11 in Neuron, could shed light on the processes underlying psychiatric conditions such as obsessive-compulsive disorder and anxiety -- not to mention how all of us cope with the deluge of information that is a feature of modern life.

"People's brains aren't well equipped to deal with the information age," said senior author Ilya Monosov, PhD, an associate professor of neuroscience, of neurosurgery and of biomedical engineering. "People are constantly checking, checking, checking for news, and some of that checking is totally unhelpful. Our modern lifestyles could be resculpting the circuits in our brain that have evolved over millions of years to help us survive in an uncertain and ever-changing world."

In 2019, studying monkeys, Monosov laboratory members J. Kael White, PhD, then a graduate student, and senior scientist Ethan S. Bromberg-Martin, PhD, identified two brain areas involved in tracking uncertainty about positively anticipated events, such as rewards. Activity in those areas drove the monkeys' motivation to find information about good things that may happen.

But it wasn't clear whether the same circuits were involved in seeking information about negatively anticipated events, like punishments. After all, most people want to know whether, for example, a bet on a horse race is likely to pay off big. Not so for bad news.

"In the clinic, when you give some patients the opportunity to get a genetic test to find out if they have, for example, Huntington's disease, some people will go ahead and get the test as soon as they can, while other people will refuse to be tested until symptoms occur," Monosov said. "Clinicians see information-seeking behavior in some people and dread behavior in others."

To find the neural circuits involved in deciding whether to seek information about unwelcome possibilities, first author Ahmad Jezzini, PhD, and Monosov taught two monkeys to recognize when something unpleasant might be headed their way. They trained the monkeys to recognize symbols that indicated they might be about to get an irritating puff of air to the face. For example, the monkeys first were shown one symbol that told them a puff might be coming but with varying degrees of certainty. A few seconds after the first symbol was shown, a second symbol was shown that resolved the animals' uncertainty. It told the monkeys that the puff was definitely coming, or it wasn't.

The researchers measured whether the animals wanted to know what was going to happen by whether they watched for the second signal or averted their eyes or, in separate experiments, letting the monkeys choose among different symbols and their outcomes.

Much like people, the two monkeys had different attitudes toward bad news: One wanted to know; the other preferred not to. The difference in their attitudes toward bad news was striking because they were of like mind when it came to good news. When they were given the option of finding out whether they were about to receive something they liked -- a drop of juice -- they both consistently chose to find out.

"We found that attitudes toward seeking information about negative events can go both ways, even between animals that have the same attitude about positive rewarding events," said Jezzini, who is an instructor in neuroscience. "To us, that was a sign that the two attitudes may be guided by different neural processes."

By precisely measuring neural activity in the brain while the monkeys were faced with these choices, the researchers identified one brain area, the anterior cingulate cortex, that encodes information about attitudes toward good and bad possibilities separately. They found a second brain area, the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, that contains individual cells whose activity reflects the monkeys' overall attitudes: yes for info on either good or bad possibilities vs. yes for intel on good possibilities only.

Understanding the neural circuits underlying uncertainty is a step toward better therapies for people with conditions such as anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder, which involve an inability to tolerate uncertainty.

"We started this study because we wanted to know how the brain encodes our desire to know what our future has in store for us," Monosov said. "We're living in a world our brains didn't evolve for. The constant availability of information is a new challenge for us to deal with. I think understanding the mechanisms of information seeking is quite important for society and for mental health at a population level."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors Bromberg-Martin, a senior scientist in the Monosov lab, and Lucas Trambaiolli, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, participated in the analyses of neural and anatomical data to make this study possible.

What The Study Did: This study of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 examines the association of anticoagulation treatment with mortality rates.

Authors: Valerie M. Vaughn, M.D., M.Sc., of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11788)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full ...

What The Study Did: Researchers compared the association between symptoms and SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels in children and adults.

Authors: Erin Chung, M.D., of the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2025)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, ...

So-called "good fatty acids" are essential for human health and much sought after by those who try to eat healthily. Among the Omega-3 fatty acids, DHA or docosahexaenoic acid is crucial to brain function, vision and the regulation of inflammatory phenomena.

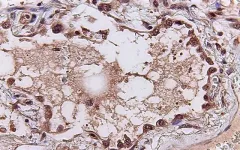

In addition to these virtues, DHA is also associated with a reduction in the incidence of cancer. How it works is the subject of a major discovery by a multidisciplinary team of University of Louvain (UCLouvain) researchers, who have just elucidated the biochemical mechanism that allows DHA and other related fatty acids to slow the development of tumours. This is a major advance that has recently been published ...

What The Study Did: Researchers examined the associations between Medicare Advantage star ratings, which are created using data from all enrollees in a plan, and disparities in care for racial/ethnic minorities and enrollees with lower income and less education.

Authors: David J. Meyers, Ph.D., M.P.H., of the Brown University School of Public Health in Providence, Rhode Island, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0793)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest ...

What The Study Did: This survey study compared features of major depression in people with or without prior COVID-19 illness.

Authors: Roy H. Perlis, M.D., M.Sc., of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16612)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study is linked to this news release.

Embed this link to provide ...

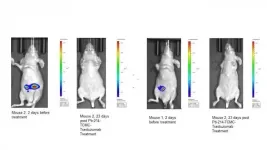

Reston, VA (Embargoed until 11:00 a.m. EDT, Friday, June 11, 2021)--Preclinical trials of a new radiopharmaceutical to treat ovarian cancer have produced successful results, dramatically limiting tumor growth and decreasing tumor mass. Designed specifically for ovarian cancers that are resistant to traditional therapies, the new radiopharmaceutical can be produced in 25 minutes at low cost, which leads to better efficiency compared with alternative methods. This research was presented at the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 2021 Annual Meeting.

According to the American Cancer Society, more than 20,000 women are diagnosed with ovarian cancer each year and nearly 14,000 ...

What The Study Did: This autopsy study examines differences in skeletal muscle and myocardial inflammation in patients who died with COVID-19 versus other diseases.

Authors: Tom Aschman, M.D., and Werner Stenzel, M.D., of the Charite-Universitatsmedizin Berlin, are the corresponding authors.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.2004)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including ...

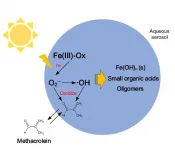

The Fenton reaction is a chemical transition involving hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and the ferrous (iron) ion, which acts as a catalyst. This process is used to destroy hazardous contaminants in wastewater through oxidation. In the atmosphere, a similar reaction, or "Fenton-like" reaction, occurs continuously with ferric oxalate([Fe(III)(C2O4)3]3-) and aerosols suspended in the air. This is the most frequent chemical reaction that occurs in the atmosphere. A particle's ability to oxidize is directly related to its phase, either gaseous or aqueous, which has an important impact on secondary organic aerosol (SOA) formation. Therefore, research is necessary not only to evaluate the contribution of this ...

Researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine used an artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm to sift through terabytes of gene expression data -- which genes are "on" or "off" during infection -- to look for shared patterns in patients with past pandemic viral infections, including SARS, MERS and swine flu.

Two telltale signatures emerged from the study, published June 11, 2021 in eBiomedicine. One, a set of 166 genes, reveals how the human immune system responds to viral infections. A second set of 20 signature genes predicts the severity of a patient's disease. For example, the need to hospitalize or use ...

Astronomers from University of Warwick and University of Exeter modelling the future of unusual planetary system found a solar system of planets that will 'pinball' off one another

Today, the system consists of four massive planets locked in a perfect rhythm

Study shows that this perfect rhythm is likely to hold for 3 billion years - but the death of its sun will cause a chain reaction and set the interplanetary pinball game in motion

Four planets locked in a perfect rhythm around a nearby star are destined to be pinballed around their solar system when their sun eventually dies, according to a study led by the University of Warwick that peers into its future.

Astronomers have modelled how the change in gravitational forces in the system as a result ...