UIC research identifies potential pathways to treating alcohol use disorder, depression

2021-06-14

(Press-News.org) A discovery from researchers at the University of Illinois Chicago may lead to new treatments for individuals who suffer from alcohol use disorder and depression.

The study, "Transcriptomics identifies STAT3 as a key regulator of hippocampal gene expression and anhedonia during withdrawal from chronic alcohol exposure," is published in the journal Translational Psychiatry by researchers at UIC's Center for Alcohol Research in Epigenetics.

"During withdrawal from long-term alcohol use, people often suffer from depression, which may cause them to start drinking again as a way to self-medicate. If we can treat that aspect, we hope we can prevent people from relapsing," said Amy Lasek, UIC associate professor of psychiatry and anatomy and cell biology at the College of Medicine, and an author of the study.

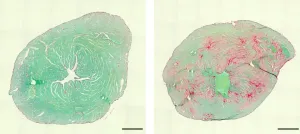

Withdrawal from chronic alcohol drinking can often result in depression. For this study, researchers removed postmortem hippocampus samples of rats in alcohol withdrawal. The hippocampus is a brain region that plays a role in depression and cognitive function. Researchers conducted RNA sequencing of all the RNA transcripts in the hippocampus and looked for those that were changed during withdrawal from alcohol.

One of the RNA transcripts that was changed makes a protein called STAT3. STAT3 is a transcription factor that controls the expression of many different genes, including immune response genes. Notably, several known STAT3-regulated genes were also increased in the hippocampus during withdrawal from alcohol, indicating that STAT3 might be a "master regulator" of several genes in the hippocampus during withdrawal.

The rats were treated during withdrawal with a compound that blocks STAT3 activity. The rats' withdrawal-induced anhedonia, or inability to feel pleasure, was alleviated.

Additionally, researchers looked at the same genes in human postmortem hippocampus samples of individuals who had a medical diagnosis of alcohol use disorder, alcoholism. They found that STAT3 and its target genes were elevated in the postmortem hippocampus of human subjects who died without alcohol in their systems -- in withdrawal or abstinent from alcohol -- when compared to samples from control subjects who did not have alcohol use disorder. These results were strikingly similar to the results found in the rat study.

"The human and rat studies are similar, which might mean that our rat results can potentially be applied to humans. We haven't done any treatments of people with alcohol use disorder, but we can see from the rat data that if we block STAT3 during withdrawal we can alleviate depression," Lasek said.

Some genes regulated by STAT3 are involved in the innate immune response in the brain. There is a known connection between hyperactive immune response and major depressive disorder, Lasek said.

"We know that chronic alcohol use can induce an immune response in the brain. By inhibiting STAT3, we think that we are dampening that hyperactive immune response by blocking the ability of STAT3 to increase the expression of these immune-response genes during withdrawal, Lasek said.

Lasek said inflammation in the brain is currently a hot research topic and further research may determine if dampening the brain's inflammatory response could treat psychiatric disorders.

Antidepressants currently available are not effective in reducing alcohol drinking. And other drugs available to treat alcohol use disorder are not universally effective. Further study for a better understanding of how STAT3 works could hopefully lead to more effective interventions for alcohol use disorder and related depression, Lasek said.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Lasek, the paper's authors are Hu Chen, Kana Hamada, Eleonora Gatta, Ying Chen, Huaibo Zhang, Jenny Drnevich, Harish Krishnan, Mark Maienschein-Cline, Dennis Grayson, and Subhash Pandey, all of UIC, and Wei-Yang Chen of the University of Washington, Seattle.

This work was funded by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (P50 AA022538 to A.W.L., S.C.P., and D.R.G.; U01 AA020912 to A. W.L.; and T32 AA026577 to K.H.) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (UL1 TR002003 to M.M.C.). S.C.P. is also supported by the senior research career scientist award from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-14

The spin of the Milky Way's galactic bar, which is made up of billions of clustered stars, has slowed by about a quarter since its formation, according to a new study by researchers at University College London (UCL) and the University of Oxford.

For 30 years, astrophysicists have predicted such a slowdown, but this is the first time it has been measured.

The researchers say it gives a new type of insight into the nature of dark matter, which acts like a counterweight slowing the spin.

In the study, published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, researchers analysed Gaia space telescope observations of a large group of stars, the Hercules stream, which are in resonance with the bar - that is, they revolve around the galaxy ...

2021-06-14

An international team of researchers led by the University of Bonn (Germany) has identified the cause of a rare, severe muscle disease. According to these findings, a single spontaneously occurring mutation results in the muscle cells no longer being able to correctly break down defective proteins. As a result, the cells perish. The condition causes severe heart failure in children, accompanied by skeletal and respiratory muscle damage. Those affected rarely live beyond the age of 20. The study also highlights experimental approaches for potential treatment. Whether this hope will be fulfilled, however, will only become clear in a few years. The results are published in the journal Nature ...

2021-06-14

A funny thing happened on the way to discovering how zinc impacts kidney stones - two different theories emerged, each contradicting the other. One: Zinc stops the growth of the calcium oxalate crystals that make up the stones; and two: It alters the surfaces of crystals which encourages further growth. Now it can be told - both theories are correct as reported in the America Chemical Society journal Crystal Growth & Design by Jeffrey Rimer, Abraham E. Dukler Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at the University of Houston, who conducted the first study to offer some resolution to the differing hypotheses.

"What we see with zinc is something ...

2021-06-14

Our ability to confront global crises, from pandemics to climate change, depends on how we interact and share information.

Social media and other forms of communication technology restructure these interactions in ways that have consequences. Unfortunately, we have little insight into whether these changes will bring about a healthy, sustainable and equitable world. As a result, researchers now say that the study of collective behavior must rise to a "crisis discipline," just like medicine, conservation and climate science have done, according to a new paper published June 14 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of ...

2021-06-14

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) -- Scientists at UC Santa Barbara, University of Southern California (USC), and the biotechnology company Regenerative Patch Technologies LLC (RPT) have reported new methodology for preservation of RPT's stem cell-based therapy for age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

The new research, recently published in Scientific Reports, optimizes the conditions to cryopreserve, or freeze, an implant consisting of a single layer of ocular cells generated from human embryonic stem cells supported by a flexible scaffold about 3x6 mm in size. ...

2021-06-14

When lithium ions flow in and out of a battery electrode during charging and discharging, a tiny bit of oxygen seeps out and the battery's voltage - a measure of how much energy it delivers - fades an equally tiny bit. The losses mount over time, and can eventually sap the battery's energy storage capacity by 10-15%.

Now researchers have measured this super-slow process with unprecedented detail, showing how the holes, or vacancies, left by escaping oxygen atoms change the electrode's structure and chemistry and gradually reduce how much energy it can store.

The results contradict some of the assumptions scientists had made about this process and could suggest new ways of engineering electrodes to prevent it.

The research team from the Department of Energy's ...

2021-06-14

MISSOULA - Those in love with the outdoors can spend their entire lives chasing that perfect campsite. New University of Montana research suggests what they are trying to find.

Will Rice, a UM assistant professor of outdoor recreation and wildland management, used big data to study the 179 extremely popular campsites of Watchman Campground in Utah's Zion National Park. Campers use an online system to reserve a wide variety of sites with different amenities, and people book the sites an average of 51 to 142 days in advance, providing hard data about demand.

Along with colleague Soyoung Park of Florida Atlantic University, Rice sifted through nearly 23,000 reservations. The researchers found that price and availability of electricity were the largest drivers of demand. Proximity ...

2021-06-14

Albeit very small, with a carapace width of only 3 cm, the Atlantic mangrove fiddler crab Leptuca thayeri can be a great help to scientists seeking to understand more about the effects of global climate change. In a study published in the journal Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, Brazilian researchers supported by São Paulo Research Foundation - FAPESP show how the ocean warming and acidification forecast by the end of the century could affect the lifecycle of these crustaceans.

Embryos of L. thayeri were exposed to a temperature rise of 4 °C and a pH reduction of 0.7 against the average for their habitat, growing faster as a result. However, a larger number of ...

2021-06-14

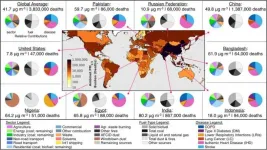

An interdisciplinary group of researchers from across the globe has comprehensively examined the sources and health effects of air pollution -- not just on a global scale, but also individually for more than 200 countries.

They found that worldwide, more than one million deaths were attributable to the burning of fossil fuels in 2017. More than half of those deaths were attributable to coal.

Findings and access to their data, which have been made public, were published today in the journal Nature Communications.

Pollution is at once a global crisis and a devastatingly personal problem. It is analyzed by satellites, but PM2.5 -- tiny particles that can infiltrate a person's lungs -- can also sicken a person who cooks dinner nightly on a cookstove.

"PM2.5 ...

2021-06-14

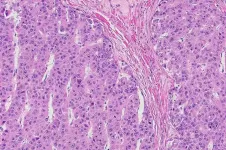

Treatment options for a deadly liver cancer, fibrolamellar carcinoma, are severely lacking. Drugs that work on other liver cancers are not effective, and although progress has been made in identifying the specific genes involved in driving the growth of fibrolamellar tumors, these findings have yet to translate into any treatment. For now, surgery is the only option for those affected--mostly children and young adults with no prior liver conditions.

Sanford M. Simon and his group understood that patients dying of fibrolamellar could not afford to wait. "There are people who need therapy now," he says. So his group threw the kitchen sink at the problem and tested over 5,000 compounds, either already approved for other clinical uses or in clinical ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] UIC research identifies potential pathways to treating alcohol use disorder, depression