Plants use a blend of external influences to evolve defense mechanisms

Findings reveal how plants use a blend of genes, geography, demography and environmental conditions to evolve defense chemicals over time

2021-06-15

(Press-News.org) Plants evolve specialised defence chemicals through the combined effects of genes, geography, demography and environmental conditions, a study published today in eLife reports.

The findings reveal a pattern in the types of defence chemicals plants produce across Europe, and describe some of the evolutionary processes that create them.

As plants are immobile organisms, they rely on producing defence chemicals called specialised metabolites for survival. Specialised metabolites have extensive variation in their structure, such as the number of carbon molecules and the other chemical groups that attach to those carbon molecules. Each plant under each environment has a unique profile of specialised metabolites as a result of genetic variation that has developed over years by different evolutionary processes and events.

"We already know that environmental pressures such as the type of herbivores that prey on plants influences the specialised metabolites plants produce," explains first author Ella Katz, Postdoctoral Researcher at the Department of Plant Sciences, University of California, Davis, US. "We wanted to understand how the intersection of environmental pressure, demography and genomic complexity gives rise to the pattern of metabolic variation across a plant species."

To do this, the team measured the variation in specialised metabolites across a population of almost 800 seed samples of the plant species Arabidopsis thaliana (A. thaliana) - a type of cress - taken from across Europe.

They looked at three locations in the plant genome known to influence A. thaliana's survival fitness as well as across the entire genome to find genes linked to metabolite production. They then grouped each gene into classes representing types of specialised metabolite, called chemotypes. This allowed them to see which chemotypes were most prevalent in different regions of Europe and reveal specific geographic patterns. For example, in central Europe and parts of Northern Europe, such as Germany and Poland, there was large variability in the chemotypes. But in southern Europe, including the Iberian Peninsula, Italy and the Balkan, there were two predominant chemotypes that were clearly geographically separated.

Next, they looked at whether these geographical differences in chemotypes were linked to weather and landscape conditions. They assigned each gene an environmental value based on its location - such as distance to the coast, rainfall in the wettest and driest months, and temperature of the warmest and coldest months. They also assigned the genes to Northern or Southern locations, based on their position relative to the Pyrenees, Alps or Carpathian mountain ranges. Using the most commonly found chemotypes, they showed that the environmental conditions had different relationships to the chemotypes that shift by geographical area. This suggests that the relationship between environmental conditions and specialised metabolites varies across different regions in Europe - so, even if wetter weather was linked to a certain chemotype in Southern Europe, this was not the same in Northern Europe.

Finally, they looked at how these genes evolved over time. Gene traits can evolve either independently within a species, called convergent evolution, or by parallel evolution, where species respond to similar external challenges in a similar way. They found that gene evolution at the three most common genome locations was shaped by a blend of events reminiscent of either parallel or convergent evolution. Moreover, the presence of variation at each of the three locations also plays a role in further shaping the evolution of the other genes. This is most likely because the effects of different specialised metabolites may work with or against each other to help the plant survive.

"Our work provides a new perspective on the complexity of the forces and mechanisms that shape the generation and distribution of specialised metabolites and affect the plant's ability to survive in a changing environment," concludes senior author Daniel Kliebenstein, Professor at the Department of Plant Sciences, University of California, Davis, and the DynaMo Center of Excellence, University of Copenhagen, Denmark. "Using a larger plant population from other locations around the world will enable us to deepen our understanding of the evolutionary mechanisms that determine the variation in a population."

INFORMATION:

Media contact

Emily Packer, Media Relations Manager

eLife

e.packer@elifesciences.org

+44 (0)1223 855373

About eLife

eLife is a non-profit organisation created by funders and led by researchers. Our mission is to accelerate discovery by operating a platform for research communication that encourages and recognises the most responsible behaviours. We aim to publish work of the highest standards and importance in all areas of biology and medicine, including Ecology and Plant Biology, while exploring creative new ways to improve how research is assessed and published. eLife receives financial support and strategic guidance from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Max Planck Society and Wellcome. Learn more at https://elifesciences.org/about.

To read the latest Ecology research published in eLife, visit https://elifesciences.org/subjects/ecology.

And for the latest in Plant Biology, see https://elifesciences.org/subjects/plant-biology.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-15

June 15, 2021 - Canadian researchers have discovered that a bee thought to be one of the rarest in the world, as the only representative of its genus, is no more than an unusual specimen of a widespread species.

Scientists with the Canadian Museum of Nature (CMN) and York University have reclassified the mystery bee, collected somewhere in Nevada in the 1870s, as Brachymelecta californica. They note that it's an aberrant individual of a species, the California digger-cuckoo bee, that is part of a group that includes five other species. All are cleptoparasitic bees, with females that lay eggs in the nests of digger bees. Brachymelecta californica itself is known to be widespread ...

2021-06-15

A recent UCLA clinical trial has shown encouraging results in helping daily smokers who are also heavy drinkers quit smoking and cut down their alcohol intake.

The study of 165 people tested two prescription drugs -- varenicline, for smoking addiction, and naltrexone, which is used to treat alcoholism. Studies have shown that varenicline, marketed under the brand name Chantix, may also be effective in reducing alcohol consumption.

Participants, who ranged in age from 21 to 65, smoked at least five cigarettes a day, with male participants generally consuming more than 14 drinks a week and women more than seven per week.

Over the 12-week study period, each participant received 2 milligrams of varenicline twice a day. Roughly half the group -- 83 participants -- also received a 50-milligram ...

2021-06-15

Hippopotamus aren't the first thing that come to mind when considering epidemiology and disease ecology. And yet these amphibious megafauna offered UC Santa Barbara ecologist Keenan Stears(link is external) a window into the progression of an anthrax outbreak that struck Ruaha National Park, Tanzania, in the dry season of 2017.

Through surveys and GPS monitoring, Stears and his colleagues, Wendy Turner, Doug McCauley and Melissa Schmitt, revealed that reduced dry-season flows in the Great Ruaha River indirectly spread the disease by affecting hippo movement. The results, which appear in the journal Ecosphere(link is external), present a unique perspective on disease ecology and illustrate how anthropogenic changes can impact wildlife and human health.

The ...

2021-06-15

A team of scientists at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) has developed millimetre-sized robots that can be controlled using magnetic fields to perform highly manoeuvrable and dexterous manipulations. This could pave the way to possible future applications in biomedicine and manufacturing.

The research team created the miniature robots by embedding magnetic microparticles into biocompatible polymers -- non-toxic materials that are harmless to humans. The robots are 'programmed' to execute their desired functionalities when magnetic fields are applied.

The made-in-NTU robots improve on many existing small-scale robots by optimizing their ability to move ...

2021-06-15

Is artificial intelligence the key to preventing relapse of severe mental illness?

New AI software developed by researchers at Flinders University shows promise for enabling timely support ahead of relapse in patients with severe mental illness.

The AI2 (Actionable Intime Insights) software, developed by a team of digital health researchers at Flinders University, has undergone an eight-month trial with psychiatric patients from the Inner North Community Health Service, located in Gawler, South Australia.

The digital tool is tipped to revolutionise consumer-centric timely mental health treatment provision outside hospital, with researchers labelling it as readily available and scalable.

In the trial of 304 ...

2021-06-15

Exposure to the rhinovirus, the most frequent cause of the common cold, can protect against infection by the virus which causes COVID-19, Yale researchers have found.

In a new study, the researchers found that the common respiratory virus jump-starts the activity of interferon-stimulated genes, early-response molecules in the immune system which can halt replication of the SARS-CoV-2 virus within airway tissues infected with the cold.

Triggering these defenses early in the course of COVID-19 infection holds promise to prevent or treat the infection, ...

2021-06-15

Researchers from The Australian National University (ANU) have developed new technology that allows people to see clearly in the dark, revolutionising night-vision.

The first-of-its-kind thin film, described in a new article published in Advanced Photonics, is ultra-compact and one day could work on standard glasses.

The researchers say the new prototype tech, based on nanoscale crystals, could be used for defence, as well as making it safer to drive at night and walking home after dark.

The team also say the work of police and security guards - who regularly employ night vision - will be easier and safer, reducing chronic neck injuries from currently bulk night-vision devices.

"We have made the invisible visible," lead researcher Dr Rocio Camacho Morales said. ...

2021-06-15

Data collected for over two decades shows that rising Baltic Sea water temperature is one of the main factors in the increasingly earlier appearance and faster growth of Baltic herring larvae.

Baltic herring (Clupea harengus membras) is commercially the most important fish species in Finland, and an important part of the Baltic marine ecosystem. Conditions during herring spawning may have cascading effects on the whole Baltic ecosystem.

According to a recent research, both developmental stages in Baltic herring larvae, small and large, have shifted their timing to earlier dates.

"This suggests that herring spawn earlier and larvae grow faster, by about 7.7 days per decade. Water ...

2021-06-15

Rising numbers of liver cancer in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities has led experts at Flinders University to call for more programs, including mobile liver clinics and ultrasound in rural and remote Australia.

The Australian study just published in international Lancet journal EClinicalMedicine reveals the survival difference was largely accounted for by factors other than Indigenous status - including rurality, comorbidity burden and lack of curative therapy.

The study of liver cancer, or Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), included 229 Indigenous and 3587 non-Indigenous HCC cases in South Australia, Queensland and the ...

2021-06-15

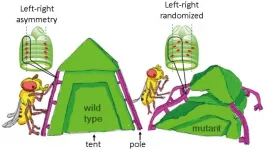

Osaka, Japan - On the outside, animals often appear bilaterally symmetrical with mirror-image left and right features. However, this balance is not always reflected internally, as several organs such as the lungs and intestines are left-right (LR) asymmetrical. Researchers at Osaka University, using an innovative technique for imaging movement of cell nuclei in living tissue, have determined the patterns of nuclear alignment responsible for LR-asymmetrical shaping of internal organs in the developing embryo.

Embryogenesis involves complex genetic and molecular processes that transform a single-celled zygote into a complete, living individual with multiple functional axes, including the LR axis. A long-standing conundrum of Developmental ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Plants use a blend of external influences to evolve defense mechanisms

Findings reveal how plants use a blend of genes, geography, demography and environmental conditions to evolve defense chemicals over time