(Press-News.org) Looking for better ways to treat patients with esophageal cancer, University of Colorado Cancer Center member Martin McCarter, MD, is investigating whether a new treatment sequence will result in better outcomes.

As they await the results of a group of clinical trials -- including one at the CU Cancer Center -- McCarter and other University of Colorado researchers (led by surgery resident Bobby Torphy, MD, PhD) looked at data from the National Cancer Database to see if they could identify other patients who have undergone the new sequence, and what the outcomes for those patients were. The group published a paper in the Annals of Surgical Oncology in April detailing their findings.

We sat down with McCarter, professor of surgical oncology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, to talk about the data and the next steps in his research.

Q: What is the motivation behind these esophageal cancer clinical trials and your review of the National Cancer Database data?

A: The big picture is that outcomes for esophageal cancer are still very poor, even in patients who can undergo an operation, and we're constantly looking for ways to improve that. The current standard of care is a combination of chemotherapy and radiation given together, followed by surgery. Treatment sequencing has evolved in other areas, particularly rectal cancer, in what is referred to as a "total neoadjuvant approach," in which patients get prolonged chemotherapy, followed by radiation therapy, then followed by surgery. They've been doing that in rectal cancer, and that has resulted in some improvements in cancer outcomes. The data for this approach in esophageal cancer is limited but in our minds it would make sense to try it. There are a couple of early-phase trials looking at that sequence, to see if it can help improve things for patients with esophageal cancer-- including an investigator-initiated study here at CU led by CU Cancer Center member Jeffrey Olsen, MD. It's going to take a few years for those trials to mature, but in the meantime, we wanted to look at a large national database to see if we could determine if other people have been using this sequence. We used the National Cancer Database to ask that question, and we found about 5% of patients were getting this prolonged sequence. Based on the data, it appears that those patients actually have a better survival rate than patients who just get chemo and radiation prior to surgery.

Q: How does the sequence you're proposing differ from the current standard of care?

A: The current standard is that patients get five weeks of radiation, and they get a little bit of chemotherapy at the beginning and in the middle of that radiation therapy. Then they wait six or eight weeks, then they have surgery. This new approach adds chemotherapy for two to three months first, then transitions to chemo and radiation therapy, and then on to the surgery. The thought behind it is that in general, people don't die from the local cancer; they die from cancer that has spread microscopically before we even see it. If we treat them aggressively with chemotherapy first, then we are attacking the microscopic disease first and then following that by trying to control the local disease with radiation and ultimately with surgery as well.

Q: Is it easy to determine from the data if someone underwent this treatment sequence?

A: It is not. We had to make some assumptions and do some pretty significant modeling to answer the question. These determinations were based on dates within the database and the fact that the patients got pure chemo, followed by pure radiation, and then they got surgery. They had to have all three of those things, and then the dates had to be separated enough such that they weren't getting the standard chemo and radiation followed by surgery. The problem is we really don't know, just from the data, why they got chemo first. Maybe doctors were making some of the same assumptions we did, which is that we ought to hit them hard first, but they were doing that without a whole lot of guidance or trials.

Q: Could using this approach eliminate the need for surgery in esophageal cancer patients?

A: That's certainly the direction things have headed in rectal cancer. People are a little less likely to avoid surgery in esophageal cancer just because the surveillance techniques are pretty inadequate. We know that a number of patients probably have a complete response to the chemo and radiation and may not need an operation; the problem is we can't really predict who those patients are, even with our best diagnostic scopes and scans.

Q: What's the next step in this research?

A: The next step is awaiting the formal results from the current trial. As a phase 2 trial, it's evaluating the potential toxicity of using this sequencing, but also evaluating the responses. Do we see better pathologic responses, and in the long term are there patients who don't need the esophageal surgery, or for those who do get the esophageal surgery, do we see improvements in overall long-term five-year survivorship? This data study was to set the table and see if we can learn any more about this sequencing strategy because we have very little to go on right now.

INFORMATION:

Rainfall associated with the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), the belt of converging trade winds and rising air that encircles the Earth near the Equator, affects the food and water security of approximately 1 billion people worldwide. They include about 11% of the Brazilian population, concentrated in four states of the Northeast region - Rio Grande do Norte, Ceará, Piauí, and Maranhão. Large swathes of these states have a semi-arid climate, and about half of all their annual rainfall occurs in only two months (March and April), when the tropical rain belt reaches its southernmost position, over the north of the Northeast region. During the rest of the year, the tropical ...

(SACRAMENTO, Calif.) -- The secret to healthier skin and joints may reside in gut microorganisms. A study led by UC Davis Health researchers has found that a diet rich in sugar and fat leads to an imbalance in the gut's microbial culture and may contribute to inflammatory skin diseases such as psoriasis. ...

New research published in the Journal of Medicinal Food suggests eating prunes each day can improve risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) including raising antioxidant capacity and reducing inflammation among healthy, postmenopausal women.

Cardiovascular disease is the number one cause of death worldwide posing a significant public health challenge.

The research led by San Diego State University reveals that prunes can positively affect heart disease risk.

"When you look at our prior research and the research of others combined with this new data, you'll see consistent ...

"Workforce issues are the most significant challenges facing the long-term care industry," states the opening editorial of a new special issue of The Gerontologist titled " END ...

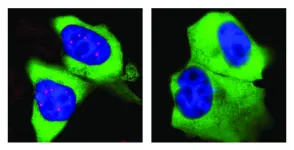

Almost all cells in our body contain a nucleus: a somewhat spherical structure that is separated from the rest of the cell by a membrane. Each nucleus contains all the genetic information of the human being. So it serves as a kind of library - but one with strict requirements: If the cell needs the building instructions for a protein, it won't simply borrow the original information. Instead, a transcript of it is made in the nucleus.

The machinery required for this is very complex, not least because the transcripts are not simple copies. In addition to essential information, genes also contain numerous passages of meaningless "garbage". They are removed when the transcript is made. Biologists call this editorial revision ...

Persons suffering from the autoimmune disease multiple sclerosis can develop various neurological symptoms caused by damage to the nervous system. Especially in early stages, these may include sensory dysfunction such as numbness or visual disturbances. In most patients, MS starts with recurring episodes of neurological disability, called relapses or demyelinating events. These clinical events are followed by a partial or complete remission. Especially in the beginning, the symptoms vary widely, so that it is often difficult even for experienced doctors to interpret them correctly to arrive at a diagnosis of MS.

Above-average numbers of medical appointments

It has been evident for some ...

The most comprehensive molecular study to date of the brains of people who died of COVID-19 turned up unmistakable signs of inflammation and impaired brain circuits.

Investigators at the Stanford School of Medicine and Saarland University in Germany report that what they saw looks a lot like what's observed in the brains of people who died of neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease.

The findings may help explain why many COVID-19 patients report neurological problems. These complaints increase with the severity of infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. And they can persist as an aspect of "long COVID," a long-lasting disorder that sometimes ...

If only it were as simple as finding more grassland for an antelope.

The story of efforts to conserve the endangered oribi in South Africa represent a diaspora of issues as varied as the people who live there. On its surface, like many threatened species, you have conflict between a need for habitat and private landownership.

But dig a little deeper and you'll uncover a seedy underbelly of political corruption, gambling, struggles over land, and racial tensions. No matter how much success is made through more traditional conservation efforts, says a new study by a University of Georgia researcher, the species ...

Rutgers scientists have used a diagnostic technique for the first time in the opioid addiction field that they believe has the potential to determine which opioid-addicted patients are more likely to relapse.

Using an algorithm that looks for patterns in brain structure and functional connectivity, researchers were able to distinguish prescription opioid users from healthy participants. If treatment is successful, their brains will resemble the brain of someone not addicted to opioids.

"People can say one thing, but brain patterns do not lie," said Suchismita Ray, lead researcher and an associate professor in the Department of Health Informatics at Rutgers School of Health Professions. "The brain patterns that ...

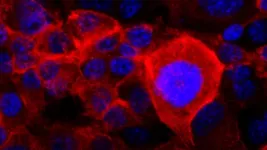

Cancer cells can become resistant to treatments through adaptation, making them notoriously tricky to defeat and highly lethal. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Cancer Center Director David Tuveson and his team investigated the basis of "adaptive resistance" common to pancreatic cancer. They discovered one of the backups to which these cells switch when confronted with cancer-killing drugs.

KRAS is a gene that drives cell division. Most pancreatic cancers have a mutation in the KRAS protein, causing uncontrolled growth. But, drugs that shut off mutant KRAS do not stop the proliferation. ...